Chris Weston looked like he wanted the floor of the Palace of Westminster to swallow him up on Tuesday, as the chief executive of Thames Water admitted to MPs that the company he runs is “extremely stressed”.

Weston had just presented another dire set of results, with Thames falling to a £1.65 billion loss in the year to March.

Meanwhile his chairman, Sir Adrian Montague, fielded multiple questions from the Commons environment committee on why Thames, which serves 16 million homes in London and the South East, continues to pay huge bonuses to senior staff.

In the same week, Susan Davy, chief executive of South West Water owner Pennon, declared that she was stepping down — a day after her company was hit with a £24 million fine for failing to run its wastewater plants properly.

And on Friday, fresh data showed river pollution incidents in England were up 60 per cent last year.

Amid the heat generated by developments like these, public outrage at Britain’s water companies is at boiling point. For years, the industry has been accused of fouling our rivers while paying out huge dividends to investors. The industry regulator Ofwat, in turn, had been blamed for keeping household water bills low at the expense of the utilities being able to fund critical maintenance. Last year, it sanctioned a large rise in bills to underpin a belated £104 billion investment in water over the next five years.

The Labour government wants to go further. It has convened an independent commission to make recommendations on reform of the sector — the biggest shake-up in more than 30 years.

Led by former Bank of England deputy governor Sir Jon Cunliffe, the commission will report back tomorrow with a blueprint for how to fix the water industry once and for all.

Steve Reed, the environment secretary

JACK TAYLOR FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

The man given the task of turning that plan into reality is Steve Reed, the secretary of state for environment, food and rural affairs. He insists Labour has already jumped in, toolbox in hand, to tackle Britain’s dodgy plumbing.

“We’ve had a big step up in bills this year because maintenance wasn’t done and wasn’t funded,” he said last week in an interview with The Sunday Times.

“The previous government could have intervened at any point and fixed that problem. They didn’t. I’ve intervened now and I’ve fixed it. So in the future, we won’t see big bill hikes again.”

Reed is adopting a three-pronged approach to the water industry. The first part is a “reset” of the industry via the Water (Special Measures) Act, which received royal assent in February and introduced potential criminal punishments for directors of failing water companies and bans on bonuses for the most senior executives.

This is populist stuff; Labour believes it plays well with the public because internal polling reveals that sewage in rivers is one of the most pressing issues on voters’ minds.

But Reed knows that frightening water companies into compliance or financial health isn’t a viable strategy on its own, so investment comes next, with the “rebuild” phase of his plan. This is where the £104 billion comes in.

“The projections were that by the mid-2030s, demand for drinking water would outstrip supply and that would lead to rationing,” he said. “Because we’ve secured this £104 billion worth of investment, we will be able to ensure that the infrastructure is in place … to guarantee water supplies for the future.”

But Reed is most keen to talk about phase three: “revolution”, an overhaul of the entire industry, which will be shaped by the Cunliffe report.

Legacy of Thatcher

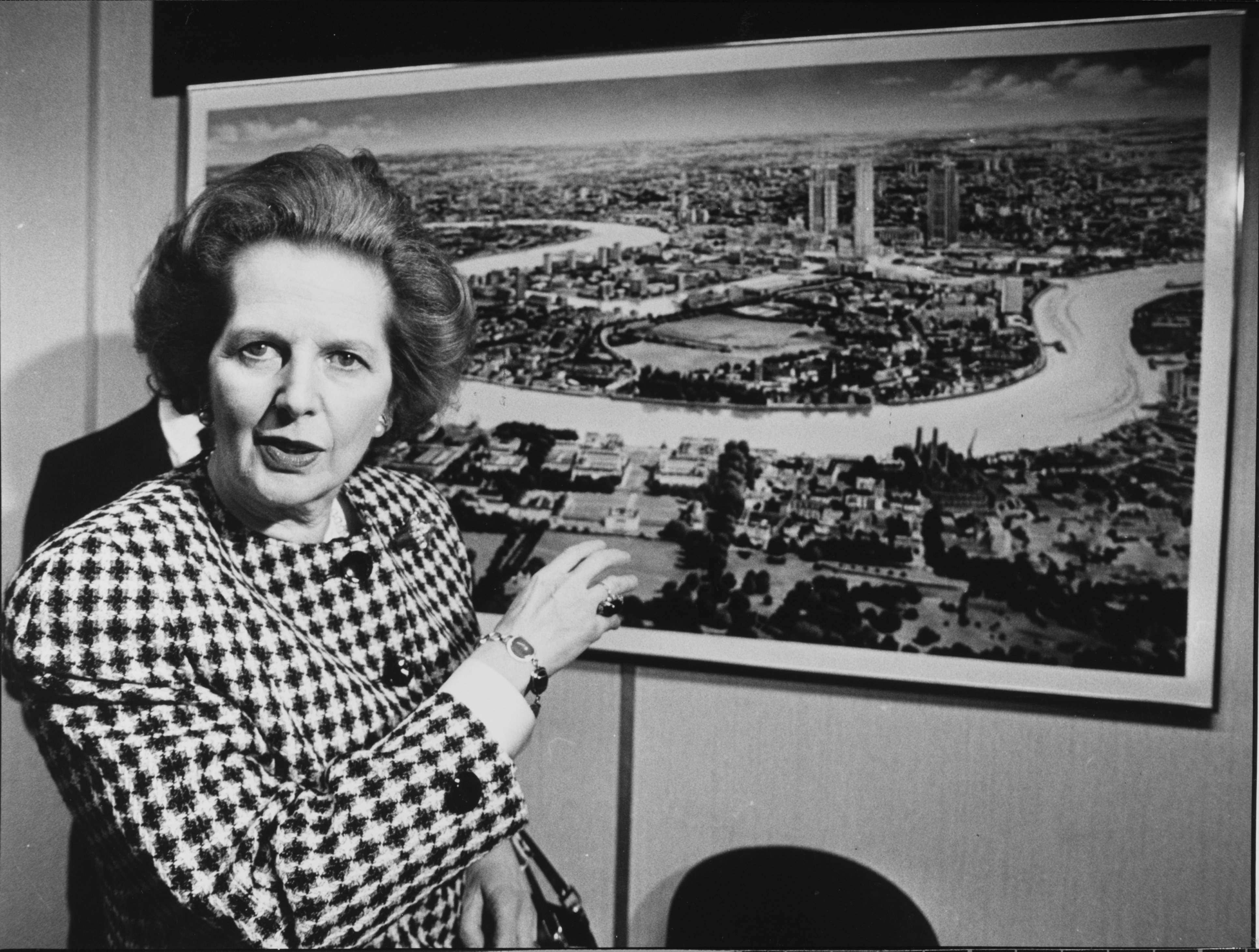

Margaret Thatcher championed privatisation as prime minister

GRAHAM WOOD/TIMES NEWSPAPERS

It is worth remembering how we got here. England’s regional water boards were privatised in 1989 under then prime minister Margaret Thatcher as ten, debt-free, listed companies. Many were later taken private; three are still listed on the stock exchange.

Over time, the owners of the water companies loaded them up with debt while extracting dividends. Ofwat kept a lid on bill increases and, after an initial spurt of investment in the 1990s, spending was broadly flat until the turn of this decade — when fraying infrastructure and the increasing challenge of climate change made the problems more apparent.

Anger over river health grew as campaigners such as the singer Feargal Sharkey drew attention to the issue. And better monitoring of sewage spills also played a part. During storms, which may be becoming more frequent, sewage works spill into rivers by design.

It would take decades and vast amounts of money to re-engineer this system.

Privatisation has had some clear successes: the quality of our drinking water has improved over the past 30 years, according to Environment Agency data. However, Reed said, a failure to plan for the future, a changing population and new demands for water from sites such as data centres have left the UK exposed: “If you see a crack in the wall of your house and you leave it for ten years, it gets worse and worse and it costs much more to fix it.”

Mogden sewage treatment works, operated by Thames Water, in west London

TOBY MELVILLE/REUTERS

A new beginning?

According to Reed, “regulation is completely broken”. Cunliffe is expected to address this head-on. In his interim report, released in June, he talked of streamlining regulation. Alongside Ofwat, the industry is governed by the Environment Agency and the Drinking Water Inspectorate, all with overlapping responsibilities.

Reports this weekend suggested he will recommend the abolition of Ofwat. Reed declined to comment on the future of the regulator, but acknowledged: “I’m very aware that Ofwat’s reputation is poor with the public and with investors.”

Cunliffe’s vision is likely to be of a new “supervisory” regime for water firms, with the regulator employing engineers who can quickly raise red flags over crumbling infrastructure. This will demand “significant change in the culture, capacity and capability of the economic regulator”, he said this year. There will be less emphasis on a “one size fits all” approach; currently, the utilities are judged against a “notional” water company, which they say does not take into account the circumstances of each firm.

Longer term, Cunliffe has recommended building more resilience into the system by setting up regional bodies to co-ordinate water planning by “catchment” — the geographic basins that capture water. Reed said this model “has a lot to commend it, because if you can manage what’s going into the water better, you can clean up the water faster”.

These regional bodies could be made up of local authorities, water companies, farmers, housebuilders and even local campaigners.

Sir Jon Cunliffe

JOSHUA BRATT FOR THE TIMES

Cunliffe’s initial findings have been broadly welcomed by the sector. “The commission identified many of the issues that have chipped away at people’s trust, including the affordability of bills and poor environmental performance,” said Mike Keil, chief executive of the Consumer Council for Water.

Outside Cunliffe’s remit is any consideration of nationalisation. Officially, Labour’s policy is that it still needs the private sector to own water companies, and lend to them. In theory, utilities should be low risk and low return. Andrew Moulder, an analyst at research firm CreditSights, explained: “If you’ve got a good-performing company in the water sector, then you are earning a relatively stable return.”

Keeping investors happy

Investor faith in Ofwat has been shaken, amid fears that the regulatory regime promotes too much risk and too little reward.

The argument goes like this: the watchdog, critics say, has kept bills low (in real terms, they have dropped in the past 15 years) and prevented companies from investing enough in infrastructure. That infrastructure then degrades, causing sewage spills or leaks, in turn earning the companies fines for missing targets. They then have even less money to turn themselves around. This is called the “doom loop”.

“Fining a company into oblivion is counterproductive in the end,” said one credit investor who is a lender to Thames Water. Constant punishment of struggling firms would put off potential new investors in the sector, they added: “What provider of fresh capital is going to invest under this regime?” Some cite the example of US private equity giant KKR, which walked away from a bid for Thames in June in part because the risks seemed too great.

Reed is aware of the dilemma. “Transformation will take time,” he said. “That’s why we will work in partnership with investors, water companies and communities to create a water system that is stable, resilient and investable.”

Protests over Thames Water’s debt restructuring plan at the High Court in February

TOBY MELVILLE/REUTERS

Sinking Thames

Reed is trying to re-engineer the sector at a time when the Thames Water drama shows little sign of abating. The utility said on Friday that it would seek more time from the regulator to reach a deal to avoid temporary nationalisation in the form of a special administration. Depending on how it manages its spending, it may have enough cash to last until May. But while it struggles to stay afloat, crucial upgrades to its pipes and facilities risk falling badly behind schedule.

Thames’s hopes lie with creditors that hold about £13 billion of its debt. The group, which includes long-term investors such as Aberdeen, as well as hedge funds like Elliott and Silver Point, is willing to swallow some losses on that debt and inject fresh money. But they want Ofwat to relent on some of the estimated £1 billion in fines that are coming Thames’ way. Reed is adamant that Thames should not get an exemption: “I think all the water companies should be treated the same in that respect. The rules apply to them all equally.”

It amounts to a high-stakes game of chicken. Should the government get it wrong, and creditors walk away, Thames Water, its running costs and at least some of its £17 billion debt will end up on the public balance sheet.

“Ultimately they’ve got to stop treating these investors like criminals,” said one City source whose institution lends to Thames. “That’s really bad for the UK.”

Additional reporting by Harry Yorke