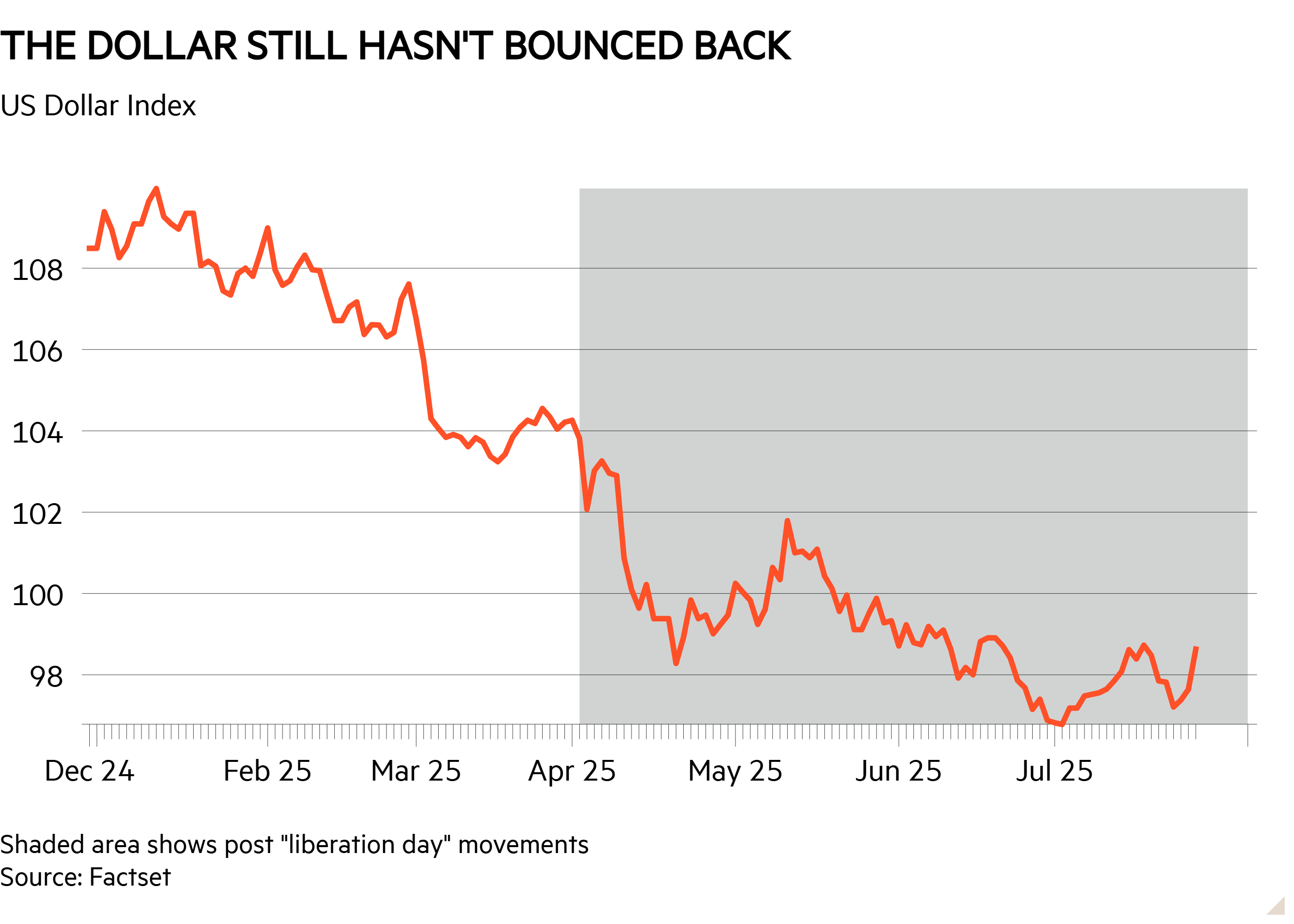

When President Donald Trump was re-elected, the consensus seemed to be that (whatever else he did) he was at least good for markets. With hindsight, that looked a little too generous. Though the S&P 500 has recovered from the ‘liberation’ day, the dollar has not. Measured against a basket of currencies, it has lost around 8 per cent since Trump’s inauguration at the start of the year, as the chart below shows.

At first, it was on/off tariff threats that rattled markets; today, it is the role of the Federal Reserve. Last week, in his latest salvo, Trump again said that though he would not try to fire Fed chair Jerome Powell, he “would love it if he lowered interest rates”.

Are Fed threats the new tariffs?

Threats to oust Powell will probably be another case of all bark and no bite, yet recent history warns us against any form of political interference with ‘independent’ central banks. In 2021, Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan fired the central bank governor after he increased interest rates in response to rising inflation. Within a year, the lira had lost 50 per cent of its value against the US dollar, inflation hit 60 per cent, and Turkish bond yields skyrocketed.

The outcome would be less extreme in a big, advanced economy such as the US – but research still suggests that interference would be destructive. Economist Thomas Drechsel looked at interactions between US presidents and Fed chairs between 1933 and 2016. He found that political pressure increased inflation strongly (in part because politicians agitate for lower rates) and the effects lingered. Even worse, rate cuts in response to political pressure didn’t work in the way that ‘normal’ rate cuts did: inflation rose with no corresponding boost to the economy.

TS Lombard economist Dario Perkins says that given all the evidence, “you would have to take a very myopic view to believe that firing Powell – or replacing him with a Trump loyalist – is ‘good’ for risk assets”.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

Higher inflation due to an eroded Fed would reduce household spending power and eat into earnings growth. Berenberg economists warn that this could trigger a market correction “in an already overvalued US equity market with narrow breadth”. Given the high exposure of US households to the stock market (around 33 per cent of US adults own shares outside of their pension, compared with 8 per cent in the UK), this would have the potential to hit the economy hard.

A compromised Fed would also unsettle bond markets. Analysts think that two-year yields would dip as markets digested the impact of a more dovish Fed chair who would presumably advocate for lower rates. At the same time, 10-year rates would rise: investors would start to demand greater compensation for locking their money away in the face of expected higher inflation – and perceived reluctance from the Fed to tackle it.

The dollar would probably fare even worse. Global investors are already nervous about the currency’s safe haven status, and any threat to the Fed’s independence will only accelerate a flight away. Analysts at Dutch bank ING warn that we could see “a highly toxic mix for the dollar”, with damage proving permanent. Currencies with ample liquidity and staunchly independent central banks could stand to benefit, and analysts highlight the euro, the Japanese yen and the Swiss franc. Trump’s Fed threats could be good for some markets – just not US ones.

Will regulatory changes help the Treasury market?

This isn’t the only possible change afoot. Fed officials are considering loosening supplementary leverage ratios (SLRs) for big banks. Currently, banks must hold capital against all assets, regardless of how risky the assets are. Critics argue that this inadvertently discourages trading in low risk assets like Treasuries: under the current rules, riskier activities can offer greater returns for the same regulatory burden.

The proposed changes would scrap today’s flat percentage, and link capital requirements to the scope of the bank’s role in the global financial system. Estimates suggest that this could free up space for big banks to hold up to $1tn more Treasuries – a boon at a time of waning overseas demand. Whether they choose to pick up the slack is another matter.

Analysts think that putting the deficit on a sustainable path ultimately matters more when it comes to Treasury demand, though changes to SLRs could help in the short term. Expanded holdings should allow banks to facilitate more Treasury market trading, increasing liquidity during times of market stress.