Earlier this month, Australia’s dominant cable TV operator replaced industry original MTV with a suite of seven custom-made music channels. These channels were provided by Nightlife Music, local to me here in Brisbane, that specializes in providing music video programming for venues of all kinds — pubs, bowling alleys, cruise ships, night clubs, office foyers and more.

Maurice Powell, Head of Production & Broadcast at Nightlife Music

Maurice Powell, Head of Production & Broadcast at Nightlife Music

Nightlife Music offers music video programming to match a venue’s style, and also a jukebox-style solution called crowdDJ which lets visitors to a venue choose what to play next. Adapting to broadcast delivery wasn’t as straightforward as you might imagine, and I spoke to Maurice Powell, Head of Production & Broadcast, to get more information on how they did it. We also spoke about how older music videos are restored to get the best possible picture quality for their customers.

This interview has been edited, and I’ve known Maurice personally for many years.

How did Nightlife Music start?

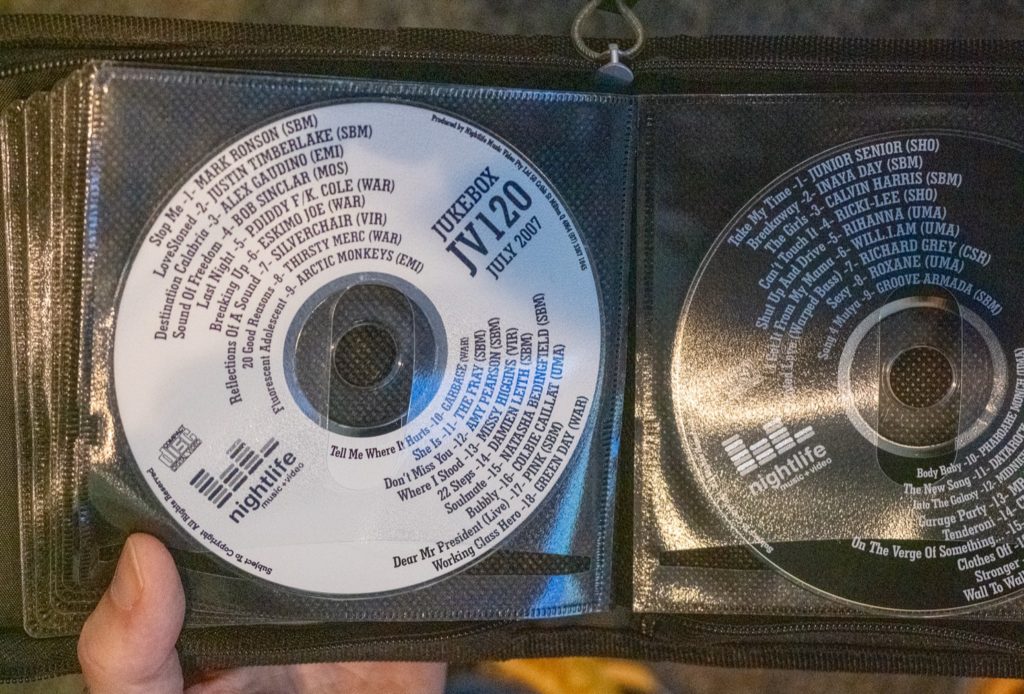

Maurice: Our founders Mark and Tim came up with this wild and crazy idea to build the world’s best music video jukebox. At the time, the competing products were the Pioneer Laser Juke, those sorts of things. It was very cumbersome stuff because those discs were produced out of the US. You had to wait long periods to get the content to come out here. Plus, you just didn’t get all that Aussie content.

Mark and Tim wanted to create a competing product, something that was targeted to our market here in Australia, and give flexibility to VJs for video mixing in venues, who’d have banks of CRTs and actually play videos live.

They ultimately landed on the format of the time, VHS: highly accessible, available, cheap, durable. Easy to replace if things go wrong, all of those sorts of things. Plus, you had the Hi-Fi Stereo audio track on VHS. Being music video meant that picture was important, but the audio had to be amazing. Hi-Fi Stereo audio meant that they could have extremely high quality audio on a domestic unit playing into a venue and it sounded great.

Remember indexing on VHS? Our jukeboxes had two VHS decks so that they could mix between the two. So they would have one playing and the other one would spool to the next song via an index set on the tape. And then that one finishes, plays the next one, just bouncing between the two. All this crazy custom stuff that they built in 1989. Insane stuff.

We got to a point and then when we started moving into digital, DVCPRO50 was the library tape format they chose at the time for good reason, it’s an excellent format. We have a nice library there. We’ve got the decks, but we’ve still got 200 of our older SVHS library tapes to digitize. Our SVHS decks are in real trouble. The time-base correctors are all gone, the component cards all have problems, they all need recapping, and it’s going to be a crazy project to get them working again.

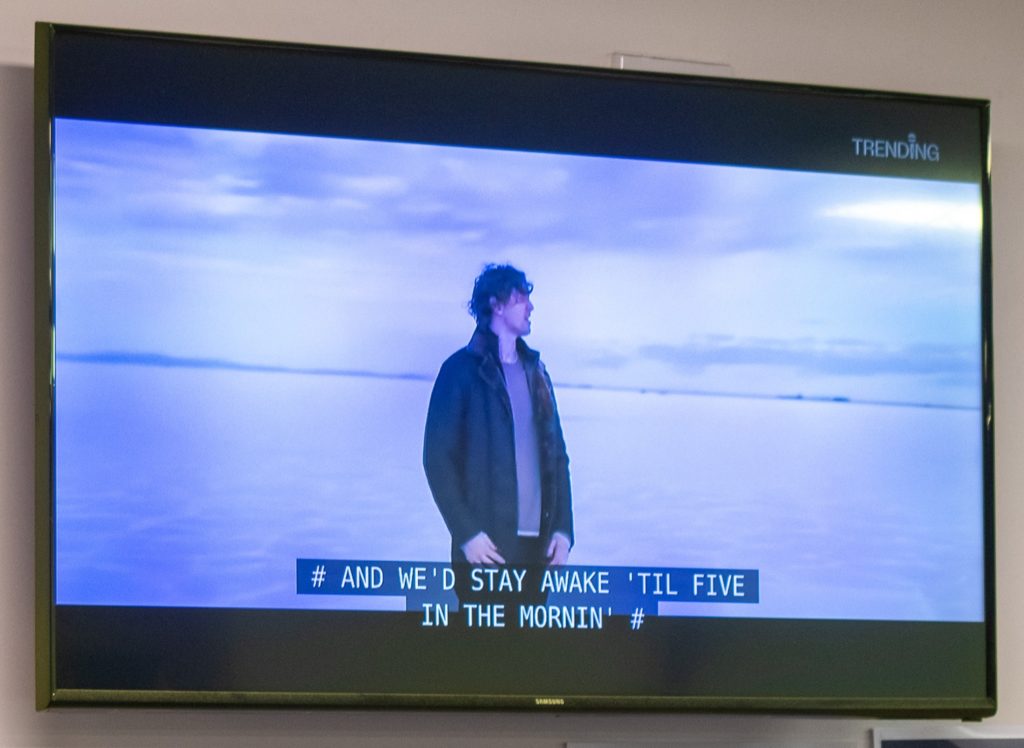

A collection of VCDs from back in the day

A collection of VCDs from back in the day

From VHS delivery we went to VideoCD, 100-disc changers, all your music videos available via control from a PC. Things progressed from there, and it evolved into hard drive-based systems, which is effectively the solution we’re still on today.

A magic box that plays music videos

We now deliver to customers via a player that can run completely offline, with 2TB of storage. The systems can run offline for months or even years if you want. We have customers that are still not fully connected to the internet all the time, presenting a challenge to deliver new content.

But when it’s online, then it will do all of its wonderful stuff in the background, deleting old stuff that’s not needed anymore, replacing it with new stuff, always updating, moving stuff around. We do all the heavy lifting so that customers don’t need to. It’s literally a set-and-forget product until you don’t want it to be anymore, and you want to fully engage and do whatever you want with it.

Our devices give the customer the ability to either choose what they want to play, or the system will play a completely custom, dynamic playlist all day. These playlists are based on a customer’s brief, and always ever-changing and updating if you wish.

Iain: What kinds of venues do you serve — bowling alleys, cruise ships, coffee shops?

Maurice: Yep, keep going. Sports bars, trampoline centres, nightclubs and pubs, all of those things and everything in between. Some of the more recent ones include things like aged care. Literally every sort of vertical you can kind of think of, we’ve touched in one way or another. And a huge one for us has been fitness and gyms.

Jukebox 2.0

Iain: The interactive product is where customers can pick the music they want next, like a custom interactive jukebox?

Maurice: Yep. We launched crowdDJ 10 years ago and it’s gone gangbusters, because people love to control music, to have a say in the music when you’re with friends, and it’s free for customers. They love it, and venues love it too. People are going to hang around longer. If they pick their song and they can see that it’s going to be five or ten songs away before they get to their song, they’re going to hang around longer, they might buy another drink, they might buy some food. So, it’s a win for everyone.

The crowdDJ logo on the side of the Nightlife building in Brisbane, Australia

The crowdDJ logo on the side of the Nightlife building in Brisbane, Australia

crowdDJ has created all these wonderful opportunities for us to do more stuff for Australian artists. Australian Played is our initiative trying to earn more dollars for Australian artists, and it became very critical during COVID, when Aussie artists could not tour.

We did a massive push over the last few years to promote Aussie music, get more visibility for it, and get more plays, which equates to more royalties and more returns for artists. And we’ve seen a significant increase. When we look at our data, it’s the power of what we do: we have a record of absolutely every song that is played across our entire network.

All that sort of metadata is there because we have to report on it to record labels and for public performance, but it’s just good, juicy data as well to also demonstrate what we’re doing for music, what we do for the industry, what we do for Australian artists. It’s very cool, very powerful stuff. We love it.

Replacing MTV

That’s a good story in itself. It’s an amazing story. One that surprised us as well.

Foxtel (Australia’s largest cable TV network) literally cold-called us out of the blue: “So we need to make some music video channels. Do you think that’s something you guys could do?” That was literally the conversation. That was about two and a half months ago. This all happened very, very fast.

We’d always romanticised the idea of doing it. The reality is a very different thing to what we could have predicted, and there were a few must-haves that we weren’t set up for yet.

This all happened because MTV were leaving Foxtel on July 1st. This came as a huge shock and a surprise for us, we’re big fans of MTV. Foxtel have customers subscribed specifically for music video channels. The Country music audience is a big one. CMT is MTV’s version and CMC, Country Music Channel, was Foxtel’s own branded version. Pre-COVID, they used to have a suite of music video channels produced in-house: Channel V, Max and CMC.

Foxtel’s new music video (and music-only) channels

Foxtel’s new music video (and music-only) channels

When COVID came around, middle of the year in 2020, Foxtel refreshed their music video channels and outsourced to MTV. Made a lot of sense, it’s MTV, you know, brand recognition. For a while they had local programming, out of the Viacom office in Sydney. But that started changing over time, and for the last couple of years, it shifted to global feeds. You could just tell that they were not programmed for Australian audiences. And this stuff was noticed by Foxtel’s customers.

Every market’s different. What charts here in Australia is different to what charts in the UK, the US. We all have different tastes. And obviously, we’ve got a lot of artists over here that don’t impact overseas, that don’t make sense in other markets as well. And Aussies want to hear that stuff. That was quite possibly the thing that got us the gig.

Demos are easy, delivery is hard

Iain: Effectively it’s like you’re creating new playlists for each of the new seven channels? You’ve got seven new customers each with new specific tailored ideals and you’re making 24-hour playlists.

Maurice: The demo that we set up was exactly that. It was seven of our Media Players in the server room, just streaming 24-7. But the big asterisk around it, and this was the thing that really threw us, was that there is government legislation now for subscription TV music channels, that 60% of all content per channel must have closed captions. In addition to that, it goes up 5% every year as well, year on year.

Maurice: What we have to deliver is a specific flavour of closed captions: Teletext. Our Media Players can’t mux in closed captions today. It’s a 12 to 24-month project to dev the software to do that. We’ve built plenty of complex stuff before, but we didn’t have the time for this project.

The broadcast team at Foxtel recommended a service called Amagi. They’re an India-based business and they are amazing. They’re the biggest broadcast cloud-based playout distribution platform that you’ve never heard of. They do tons of FAST [Free, Ad-Supported Television] channels for broadcasters all over the world. This has been a very fortuitous exercise for everyone, us and them, and they very quickly identified this project as a strategic one that they really wanted to get across the line.

The tools that they’ve built are amazing, though not entirely geared for music video channels. The workflow is tailored for episodic and feature length content, content that has ad breaks. Lots and lots of short form content, such as music videos, is where it’s been a real eye opener. But together with the team at Amagi we made it work brilliantly. The outcome has been amazing.

Amagi have a playout platform and that is where the magic happens: here’s the assets, here’s the captions, mux it all in, spit it out as high bitrate SRT streams. Deliver that to Foxtel and Bob’s your uncle, it’s amazing! It’s a game changer for broadcast TV, and this stuff will change everything. This platform has enabled us to be able to deliver this project. We couldn’t have done it otherwise. We certainly couldn’t have turned it around in six weeks.

Promoting Australian content

Foxtel wanted seven channels: Trending, Retro, CMC, Max, Kids, Club, and there was talk of a rock channel originally. And as discussions went on, we got to a point and we suggested, “You know what, instead of a rock channel, How about we do an all Aussie channel?”

Having a 24-7 all-Aussie channel is just a wonderful thing to do. And to be able to do it and make it visual, do music video all day, every day, I mean, it’s such a unique offering. We’re really proud of it. Super cool.

We’re also doing special shows that run for a week only. We did the Cold Chisel one this week. So out of the gate, the very first special was Cold Chisel’s entire video back catalogue, two hours from start to finish.

The first song is important

Iain: I thought you might have played Skyhooks, as a homage to Double J’s launch?

(For international readers, Double J launched in Sydney in 1975 with a provocatively titled track by Skyhooks: “You Just Like Me ‘Cos I’m Good in Bed”.)

Maurice: MTV was Video Killed the Radio Star, right? So, what’s the first music video going to be that we play? I Love The Nightlife! (the Priscilla version, not this original version!) with Hugo Weaving in the music video. That was our launch, 6 am on the Retro channel.

The feedback has been overwhelmingly positive from Foxtel’s customers. They’re getting positive feedback on their complaints forum, which apparently never happens. This is the bit that we are ultra proud of, customers are saying “We can tell it’s programmed by Aussies for Aussies. We love this music, it makes sense to us, and it’s amazing.” And the next bit, which is a bit I’m very, very proud of, is: “And the picture and sound quality is better than what we had before.”

Making it look good

There is a whole lot of mixing and matching that that happens through the process. With broadcast TV in Australia, we’re like the UK, we’re PAL 50 Hz based, and it’s interlaced, and so it’s about getting all content and shoehorning it in to make it work, play out on air and conform to a spec.

The channels are actually standard def at the moment. They want to get them upgraded at some stage, but there’s only so much bandwidth available right now. We are delivering HD to them where possible. We also have some very old content that is SD. And then we’ve got very current content that is 4K, and everything in between, depending on who’s made it, what the budget was, who the artist is. So there’s a great variance in there.

There’s so many aspects to this stuff, and so this is a lot of what we do every day. We have to basically R&D every single music video because you never know exactly, what the source was, where it was made, all these sorts of things, you kind of have to work it out. Who’s the artist? What country are they from? If it was produced in the US, if it was produced in the 70s or 80s, it was probably potentially shot on film, cut on tape, thus natively probably 29.97i. If shot on film, it was probably shot at 23.976 and then telecined with 3:2 pulldown. You kind of have to think about this stuff, work it out, and undo some of those unavoidable evils that were done.

Back in those days, when you edited on tape, you’ll insert a shot here, then you’ll insert another one, but the cadence changes between the two shots. So if you try and undo the 3:2 pulldown in that shot, It’s not consistent over to the next shot. The cadence is ever-changing over the course of a three and a half minute song. There’s work that’s involved in reversing this, and it’s a project.

We try to output as native as possible, as we can mix and match all sorts of frame rates on our Media Player that does the heavy lifting on playout. Our Media Players are Windows-based devices, using IoT [Internet of Things] versions, so it’s the most lightweight version of Windows you can get. But it gives us a lot of flexibility. Some of our customers are still running older video distribution technologies like RF modulation and composite across venues. We’ve got graphics cards on some models where we can for example provide interlaced 50 Hz straight out, the exact requirements that they need. We’re basically doing dynamic standards conversion on the fly.

Music videos are the Wild West

If anyone ever thought there was any consistency in the way that music videos have been produced, forget it. Decades worth of just everyone kind of doing whatever they wanted, which is part of the charm. In so many cases, stuff is done at super tight budgets, super fast turnarounds. If you’re Joseph Khan doing Taylor Swift music videos, sure, there’s money in that. But that’s a very small percentage of the industry.

The files we get now, some of the big ones are the exports directly from the timeline from the edit suite. We’ll get ProRes 4444 for a three and a half minute song at absolutely massive file sizes, but the quality is stunning.

Currently, we’re keeping the serviced assets in their native form, though we are investigating alternative archival formats to try and keep storage down. But as soon as you go to another format, and particularly one that’s lossy, even if it’s low loss, you’re changing the noise profile, which means that if you ever need to come back and redo something, your source is now different so you may not get the same outcome as before. It’s really challenging.

A high percentage of newer stuff is ProRes, though we still get a lot of deliveries just in H.264. We completely understand that the record labels’ people need to be able to play it themselves on their laptops. So a big 4444 ProRes is not very useful for them. If they can open it up in VLC or whatever and it plays, then everyone’s happy, so we do get a fair amount of high bit rate H.264.

Restoring music videos

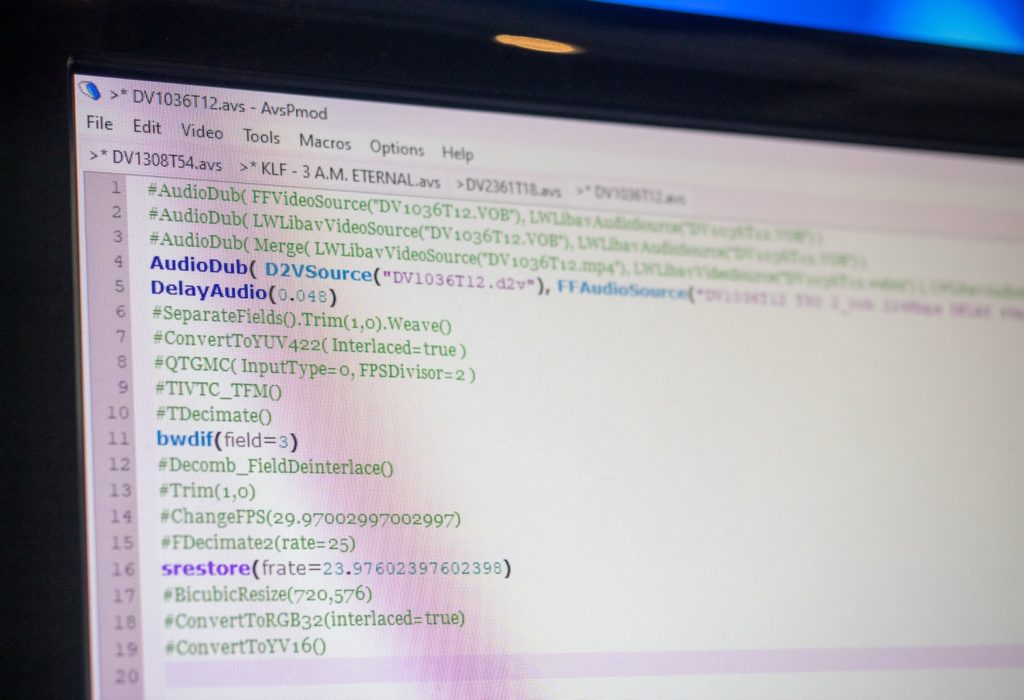

We’ve done so much R&D looking at the best workflows and solutions. And in most cases, they are not necessarily the Hollywood big expensive solutions. For deinterlacing, we love the script-based, enthusiast, community-driven tools that are out there, like AviSynth and QTGMC. And we love Neat Video too for video noise reduction.

But there’s never one tool or one setting that fits all. It does not exist, especially with stuff like music videos, because everything is different. But it’s about trying to strike a balance because we can’t spend too long on this stuff either as it’s really time consuming. How can we make it look really good for our customers and viewers, with this amount of time and resources.

Some of the secret sauce behind the video processing

Some of the secret sauce behind the video processing

In some ways we think of ourselves as the caretakers of this content, like librarians, we’re extremely passionate about it. So we try and make it the best version that we can for out there in the wild. It’s a funny thing that we do. Even though we didn’t make it, we have a bit of a responsibility to our customers. They come to us because they know that they’re going to get a quality product that’s going to look and sound good in their venues. Because otherwise, they’re just going to maybe load up YouTube and just stick it on shuffle and let it rip, and that just doesn’t work.

Archiving the world’s music videos

Many big bands on major labels have been lucky enough to have the resources to go to great lengths to restore and preserve their videos, which in some cases meant going back to the original film negatives and transferring to 4K, but there’s lots of artists and content that that has not happened for. There’s this weird world of catalogues just disappearing over time. We like to think we do our best, as all content like this needs to be preserved because it’s really valuable both culturally and for our customers.

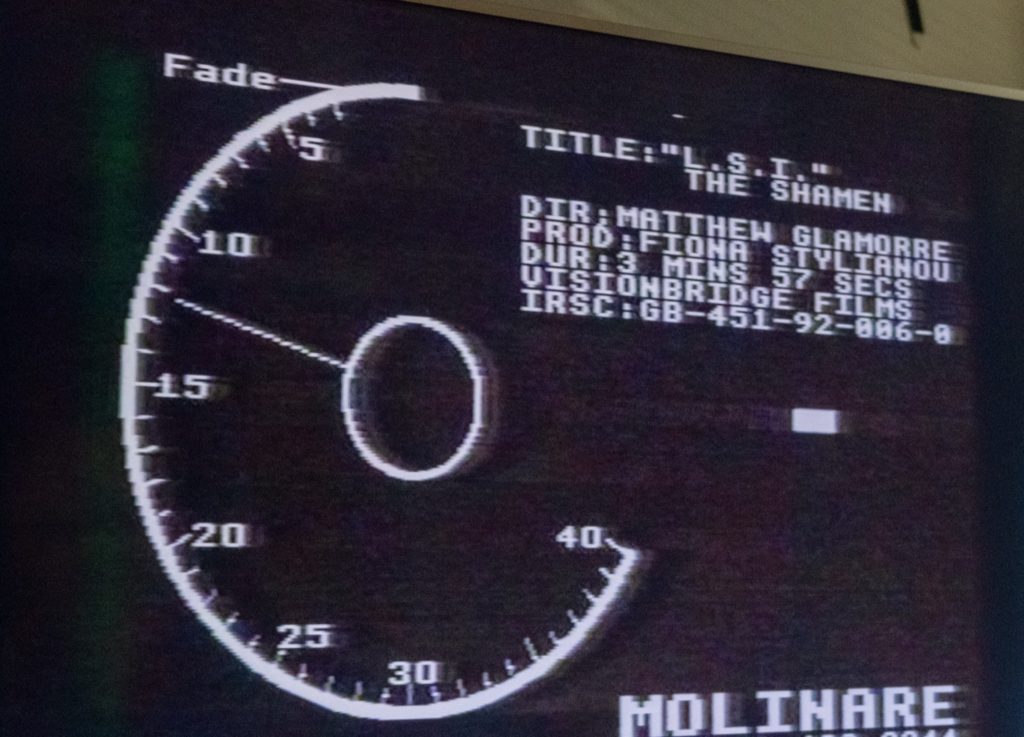

Heres the original pre-roll for classic clip LSI: Love Sex Intelligence by The Shamen

Heres the original pre-roll for classic clip LSI: Love Sex Intelligence by The Shamen

I love this song (LSI) but you can’t even watch an official copy of it on YouTube because The Shamen don’t have a YouTube channel. We do our bit to try and preserve this stuff, and make it look and sound good.

Several episodes of Bluey dubbed into Japanese scroll by

Several episodes of Bluey dubbed into Japanese scroll by

It turns out that Nightlife is handling the video at the Australian Pavilion at the World Expo in Osaka, Japan.

Maurice: We’re doing all of their content that goes on screens, and we’ve supplied all the Media Players for all of their spaces, including their 12-meter screen in the Forecourt which is running a custom 4K res. Another one of those crazy special projects that we’re doing. But next week they kick off Bluey O’Clock. The BBC have supplied the Japanese versions.

Back to The Shamen, where we’re looking at an original production version transferred from SVHS to the DVCPRO codec.

Maurice: There’s a few things about this that I’m actually not happy with. If you’ve ever had anything to do with DV, all of the DV codecs hate red. And what you’re seeing there is the weird anomalies between fields. We’re only seeing one of the fields at the moment, so you’re seeing the horizontal lines.

Chroma sampling for DV in NTSC was 4:1:1, PAL is 4:2:0, though DVCPRO50 bumped this up to 4:2:2. Still challenging stuff to work with.

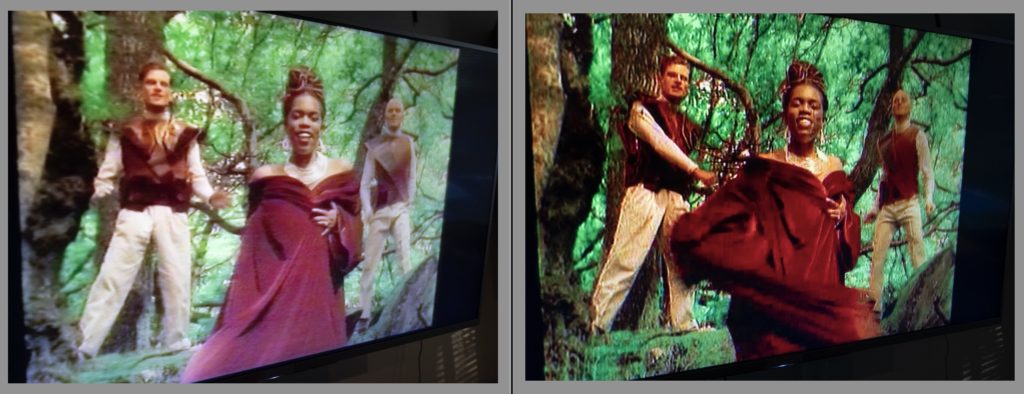

I find it’s often good to cross reference with alternate sources too for comparison, to get an overall idea of how it’s supposed to look. I have The Shamen’s Greatest Hits DVD collection, and compared the two sources looking at things such as video noise and grain, colours and saturation.

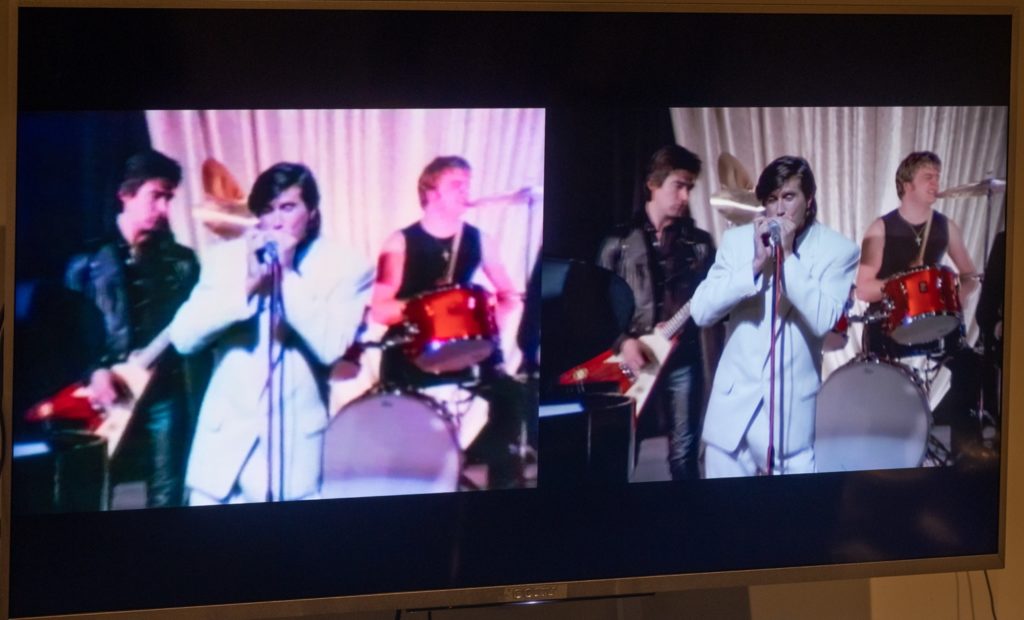

The original SVHS dub on the left, vs the official DVD (too sharp and saturated for my taste) on the right

The original SVHS dub on the left, vs the official DVD (too sharp and saturated for my taste) on the right

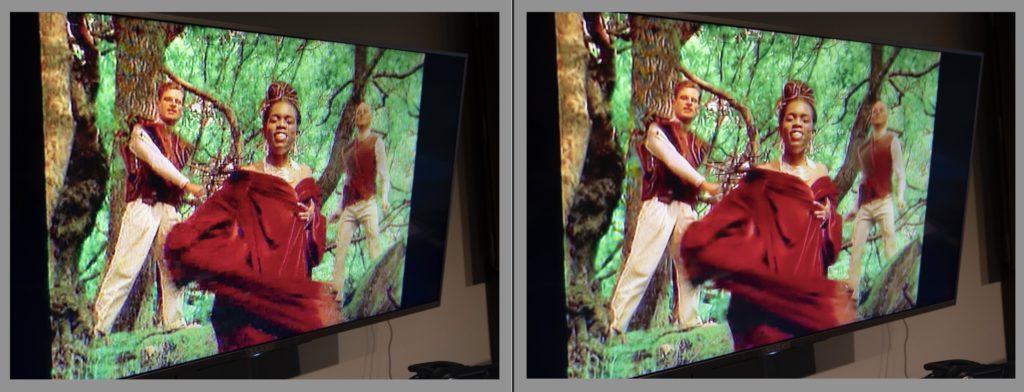

We pre-process before taking it into Premiere, because the deinterlacer in Premiere is a fairly basic bob deinterlacer (line doubling, see here for more). AviSynth with QTGMC does a superior job of deinterlacing, and is our preferred tool for the job, but it is slow. It does motion-compensated deinterlacing to reconstruct progressive frames from interlaced sources. If speed is important, we’ll use bwdif which is also available in AviSynth, and has since been ported to FFmpeg as a filter.

So all I ended up doing was pre-processing using bwdif deinterlacing and then outputting using the Ut Video codec, a free lossless AVI codec that’s very handy on Windows for SD content.

This deinterlaced version is then taken into Premiere Pro where Neat Video processes it further; the before/after comparison is pretty impressive

This deinterlaced version is then taken into Premiere Pro where Neat Video processes it further; the before/after comparison is pretty impressive

Maurice: Let me show you though something else. Bryan Ferry released a big greatest hits DVD compilation, and did a rescan of the original music video from the original film. We love it when they’ve already done the remastering work, it’s amazing.

Bryan Ferry’s remaster needed no work at all

Bryan Ferry’s remaster needed no work at all

And with that, we’d run out of time.

Nightlife Music occupies a unique spot in the music business. Though they’re not the only archivers in the country, there aren’t many others left, and music video is an important part of modern cultural history. If you ever make a music video for a client, send Nightlife a copy — just maybe not in ProRes 4444.