Trade

By Christopher Towe·July 30, 2025

Independent Economic Consultant

The Issue:

Canada’s economy is highly integrated with the U.S. economy, a consequence of, among other factors, the lengthy shared border and a long history of free-trade arrangements. However, these close ties have been upended as a result of the Trump Administration’s recent tariff measures. Although some of these measures have been scaled back or delayed, tariff rates between the United States and Canada still remain significantly higher than before the trade war. Canada’s economy is highly vulnerable to disruptions in trade with the United States and has limited scope for introducing retaliatory tariffs without exacting an even greater toll on the Canadian economy.

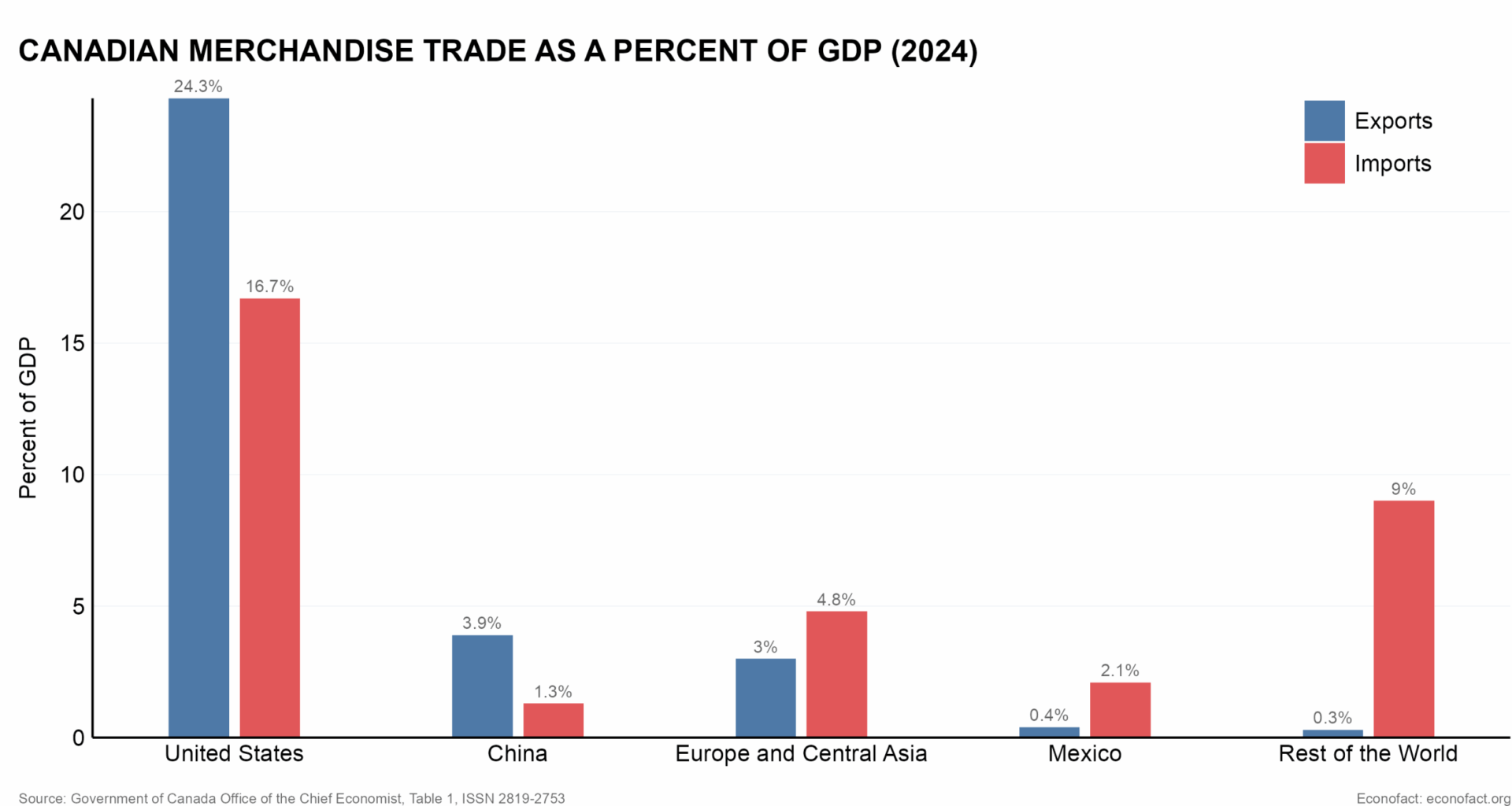

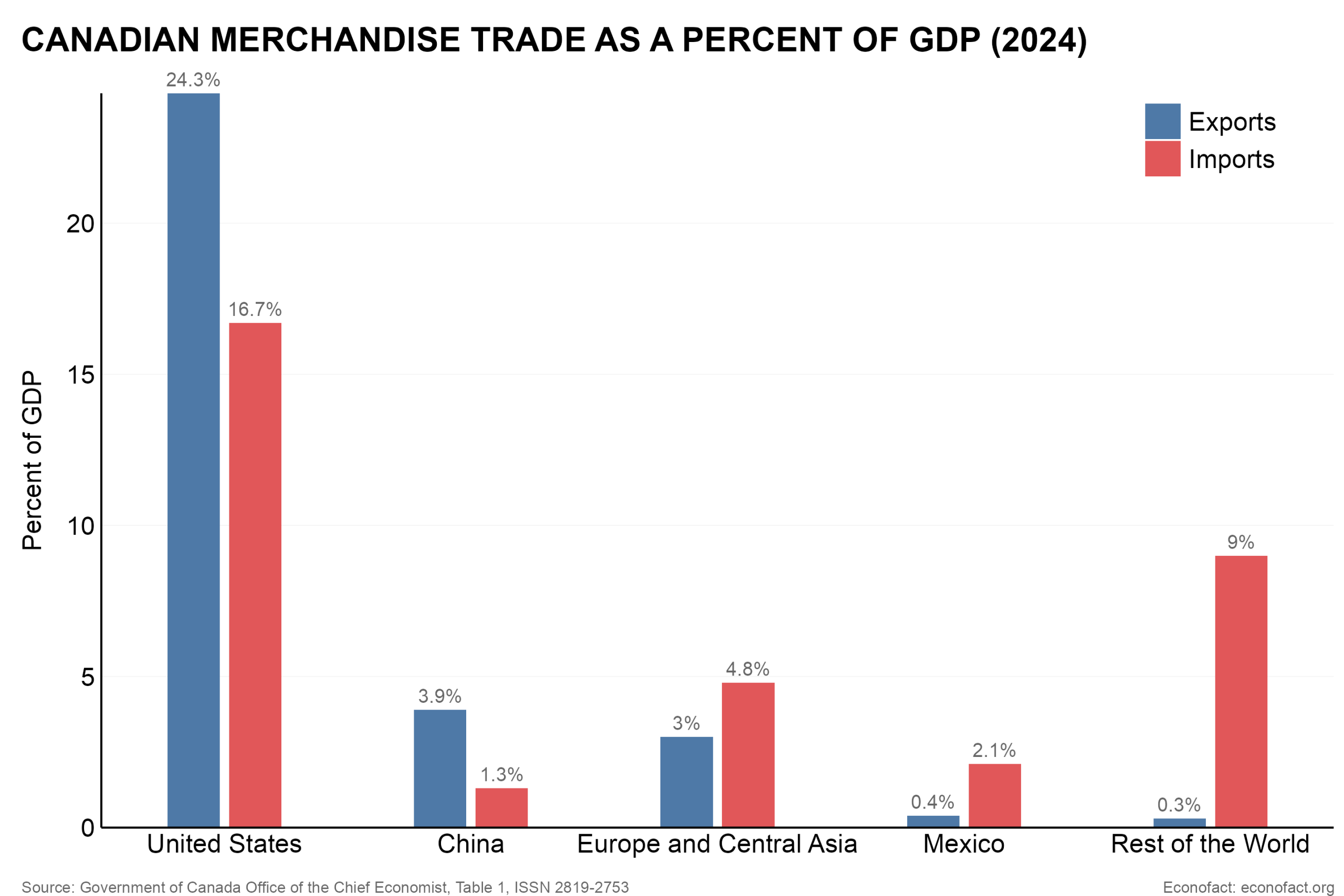

Roughly three quarters of Canada’s merchandise exports, representing almost one-quarter of its GDP, are directed to the United States.

The Facts:

The Canadian economy is highly trade dependent and the United States is by far its most important trading partner. The sum of Canadian imports and exports was two-thirds of its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2024 – by contrast, the United States’ imports and exports were one-quarter of its GDP in that year. Roughly three quarters of Canadian merchandise exports are directed to the United States, representing almost one-quarter of Canadian GDP, and imports from the United States represent 16.7% of Canadian GDP. No other country or region comes close to this level of trade integration with Canada (see chart). Canada ran a trade surplus with the United States of about C$170 billion in 2024, but this is largely explained by U.S. imports of Canadian oil and other energy products. Excluding these products the United States ran a trade surplus with Canada that year.

Much of Canadian trade with the United States represents the integration of cross-border supply chains. These supply chains are particularly important for the auto industry and energy. In 2024, roughly a third of Canada’s exports to the United States was in the category of oil, gas and other energy products, and about 15 percent was in the motor vehicles and parts category. It is estimated that 17 percent of Canadian merchandise exports to the United States were initially produced in the United States, further processed in Canada, and then re-exported. These linkages are particularly important for the auto sector, where Mexico also plays a key role. Indeed, it has been estimated that North American auto parts cross all three borders multiple times prior to the final assembly of a vehicle. Only about 12 percent of Canadian exports to the United States was final consumer goods while the remainder were mostly raw materials, industrial machinery, and other intermediate goods.

There has been controversy on both sides of the border about recent trade agreements. The 1988 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA) raised fears in Canada of a loss of sovereignty and of lower-cost competition from U.S. companies (see here). Its successor, the trilateral 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) built on the provisions of CUSFTA by including safeguards designed to limit risks of economic dislocations from the inclusion of Mexico and its relatively low wages (what Ross Perot memorably described as the “giant sucking sound of jobs being pulled out of [the] country”). In general, studies tend to find that the impacts of NAFTA on the United States were “relatively modest,” but there were significant worker and firm adjustment costs in certain regions and industries. The CUSFTA was found to initially have caused significant employment losses among import-competing industries (see here) but recent research finds little impact on the long-run cumulative earnings of displaced workers as they quickly transitioned out of industries facing import competition. Most commentators acknowledge, however, that it is difficult to disentangle the broader effects of the trade agreements from the effects of the 2007 financial crisis, globalization and increased competition from China, and the growing role of robotics and other technologies in manufacturing.

President Trump replaced NAFTA with the U.S.- Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). There had been complaints from the United States about NAFTA’s dispute settlement system and its failure to address Canadian restrictions on many imports, including softwood lumber, and many agricultural products such as dairy and eggs. Threats of withdrawal from NAFTA by President Trump, led to its replacement by the USMCA, which entered into force July 1, 2020. The USMCA maintained NAFTA’s tariff and non-tariff market-opening provisions but modified the dispute settlement mechanisms, improved access for U.S. producers to the Canadian dairy market, raised the domestic content requirement for autos from 62.5 percent to 75 percent, and tightened labor standards, environmental protections, and digital trade provisions. The USMCA is scheduled to be reviewed in 2026, and to sunset after 16 years.

The Trump Administration has already levied tariffs on Canadian goods. President Trump has announced a 50% tariff on aluminum and steel, a 25% import tax on vehicles and other Canadian imports, and 10 percent rate applied to energy imports (see here). But Canadian goods entering the United States under USMCA are currently exempt from these tariffs — this covers only about 38 percent of Canada’s exports to the United States, while a further 58 percent of Canadian exports to the United States could also be eligible. (Exporters of these products are thought to have not previously availed themselves of the treaty’s benefit because low U.S. tariffs on these goods did not outweigh the USMCA’s documentation and other compliance costs.) On July 10, President Trump announced the United States would further raise tariffs on Canadian goods to 35%, effective August 1. These moves are not unique to Canada – since his inauguration, President Trump has imposed, suspended, raised, and partially rolled-back tariffs on many countries. (See here for an updated trade tracker). One rationale for these policies has been to narrow bilateral trade deficits. Another rationale, announced in February, was to counter the “threat posed by illegal aliens and drugs” from Canada, Mexico and China.

Canada has introduced retaliatory tariffs on a small share of its imports from the United States. A 25 percent tariff was introduced in March on products said to be valued at C$30 billion and subsequently a 25 percent tariff was applied to steel, aluminum, and some other imports. In early April, Canada imposed a 25 percent tariff on non-USMCA compliant autos imported from the United States and on non-Canadian and non-Mexican content of USMCA compliant autos. However, tariff exemptions were also introduced to mitigate the impact on domestic manufacturers; as a result, at least one analysis suggested that the effective increase in tariffs on U.S. imports was near zero. Indeed, a number of recent studies have illustrated that Canada’s relatively small size and high trade openness mean that retaliatory tariffs would have a limited impact on the United States but impose additional economic costs on Canada.

The Canadian economy is already being affected by the tariffs and associated uncertainty. Bank of Canada Governor Macklem in a recent speech noted that employment had plunged in sectors reliant on exports to the United States, and that business expectations for hiring have weakened considerably. In response, the Bank of Canada cut its policy rate in January and March 2025, citing “pervasive uncertainty created by continuously changing US tariff threats [that] is restraining consumers’ spending intentions and businesses’ plans to hire and invest.” The effects have been most noticeable in Southern Ontario, where much of Canada’s auto sector is located. One report notes that the small-scale parts sector, which faces fewer barriers to moving plant and equipment to the United States, has already experienced significant layoffs.

Looking forward, estimates of the longer-term economic impact of the U.S. tariffs on Canada depend on assumptions regarding the level and duration of the U.S. tariffs imposed, and on the retaliatory measures taken by other countries. One study by the Peterson Institute estimates that the initially proposed U.S. tariffs on Canadian imports could lower Canadian GDP by around 1¼ percent by 2027, and another study by the Yale Budget Lab estimated that the level decline in Canada’s GDP would be nearly 2 percent in the long run, an order of magnitude higher than for other countries. The Bank of Canada published estimates suggesting that a 25 percentage point increase in tariffs by the U.S. and a 25 percentage point increase in tariffs by Canada in retaliation would result in a further drag on Canadian GDP.

The importance of trade for Canada’s economy and the degree to which this depends on trade with the United States, mean that its economy is particularly vulnerable to U.S. tariff hikes and that its scope for effective unilateral retaliation is limited. As some commentators have noted, this puts the premium on Canada working with the United States to resolve long-standing trade irritants, including in the context of the review of the USMCA that was already scheduled for 2026, but also to tackle issues related to border security and the significant shortfall in Canada’s defense spending relative to NATO objectives. At the same time, there is scope for Canada to diversify and deepen its trade relationships with other countries, and to address some of the structural factors that have weighed on the country’s competitiveness and productivity. In this context, the federal government has announced efforts to reduce barriers to interprovincial trade barriers—which include licensing requirements, regulations, and provincial agricultural market board—and Ontario and some other provinces have moved to those restrictions that are under their purview.