When President Donald Trump rolled out a plan to boost artificial intelligence and data centers, a key goal was wiping away barriers to rapid growth. The AI Action Plan that Trump announced last week would seek to sweep aside the National Environmental Policy Act to streamline environmental reviews and permitting for data centers and related infrastructure.

Republicans and business interests have long criticized NEPA for what they see as unreasonable slowing of development, and Trump’s plan would give “categorical exclusions” to data centers for “maximum efficiency” in permitting.

A spokeswoman for the White House Council on Environmental Quality said the administration is “focused on driving meaningful NEPA reform to reduce the delays in federal permitting, unleashing the ability for America to strengthen its AI and manufacturing leadership.”

“It’s par for the course for this administration. The attitude is to clear the way for projects that harm communities and the environment,” said Erin Doran, senior staff attorney at environmental nonprofit Food & Water Watch.

NEPA is a foundational environmental law in the United States, “essentially our Magna Carta for the environment,” said Wendy Park, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, referring to the 13th century English legal text that formed the basis for constitutions worldwide.

Signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1970, NEPA requires federal agencies proposing actions such as building roads, bridges or energy projects to study how their project will affect the environment. Private companies are also frequently subject to NEPA standards when they apply for a permit from a federal agency.

In recent years, the law has become increasingly important in requiring consideration of a project’s possible contributions to climate change.

“That’s a really important function, because otherwise we’re just operating with blinders just to get the project done, without considering whether there are alternative solutions that might accomplish the same objective, but in a more environmentally friendly way,” Park said.

But business groups say NEPA routinely blocks important projects that often take five years or more to complete.

“Our broken permitting system has long been a national embarrassment,” said Marty Durbin, president of the U.S. Chamber’s Global Energy Institute. He called NEPA “a blunt and haphazard tool” used to block investment and economic development.

The White House proposal comes as Congress is working on a permitting reform plan that would overhaul NEPA, addressing longstanding concerns from both parties that development projects — including some for clean energy — take too long to be approved.

Trump sought to weaken NEPA in his first term by limiting when environmental reviews are required and limiting the time for evaluation and public comment. Former Democratic President Joe Biden restored more rigorous reviews.

An executive order that touched on environmental statutes has many agencies scrapping the requirement for a draft environmental impact statement. And the Council on Environmental Quality in May withdrew Biden-era guidance that federal agencies should consider the effects of planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions when conducting NEPA reviews.

Separately, the U.S. Supreme Court in May narrowed the scope of environmental reviews required for major infrastructure projects. In a ruling involving a Utah railway expansion project aimed at quadrupling oil production, the court said NEPA wasn’t designed “for judges to hamstring new infrastructure and construction projects.”

John Ruple, a research professor of law at the University of Utah, said sidelining NEPA could actually slow things down. Federal agencies still have to comply with other environmental laws, like the Endangered Species Act or Clean Air Act. NEPA has an often overlooked benefit of forcing coordination with those other laws, he said

A botanist by training, Mary O’Brien was working with a small organization in Oregon in the 1980s to propose alternative techniques to successfully replant Douglas fir trees that had been clear-cut on federal lands. Aerially sprayed herbicides aimed at helping the conifers grow have not only been linked to health problems in humans but were also killing another species of tree, red alders, that were beneficial to the fir saplings, O’Brien said.

The U.S. Forest Service had maintained that the herbicides’ impact on humans and red alders wasn’t a problem. But under NEPA, a court required the agency to redo their analysis and they ultimately had to write a new environmental impact statement.

“It’s a fundamental concept: ‘Don’t just roar ahead.’ Think about your options,” O’Brien said.

O’Brien, who later worked at the Grand Canyon Trust, also co-chaired a working group that weighed in on a 2012 Forest Service proposal, finalized in 2016, for aspen restoration on Monroe Mountain in Utah. Hunters, landowners, loggers and ranchers all had different opinions on how the restoration should be handled. She said NEPA’s requirement to get the public involved made for better research and a better plan.

“I think it’s one of the laws that’s the most often used by the public without the public being aware,” said Stephen Schima, senior legislative counsel at environmental law nonprofit Earthjustice. “NEPA has long been the one opportunity for communities and impacted stakeholders and local governments to weigh in.”

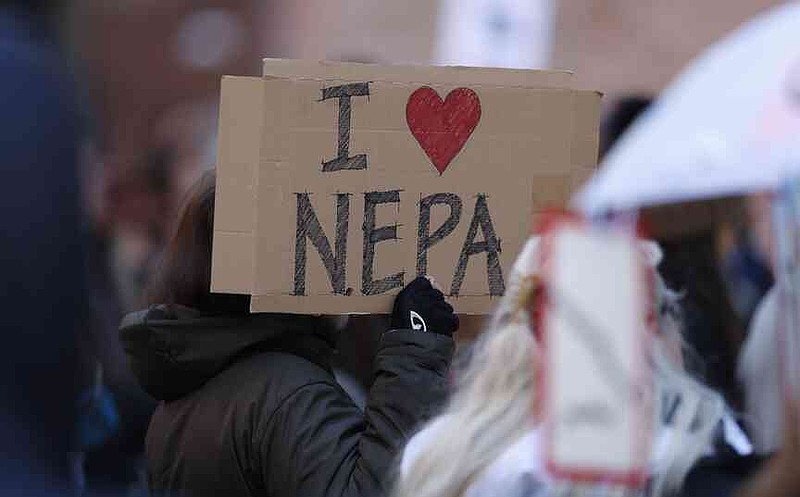

FILE – Joan Lutz, of Boulder, Colo., waves a placard at a rally of advocates to voice opposition to efforts by the Trump administration to weaken the National Environmental Policy Act, which is the country’s bedrock law aimed at protecting the environment, on Feb. 11, 2020, in Denver. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski)

FILE – Joan Lutz, of Boulder, Colo., waves a placard at a rally of advocates to voice opposition to efforts by the Trump administration to weaken the National Environmental Policy Act, which is the country’s bedrock law aimed at protecting the environment, on Feb. 11, 2020, in Denver. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski)