This is the second of a two-part series on Radiant Industries’ proposed microreactor facility in Natrona County. Part I introduced the project, its technology, the company and Wyoming’s nuclear ambitions. Part II will explore the challenges, community concerns and legislative hurdles surrounding the project.

BAR NUNN, Wyo. — Natrona County stands at a nuclear crossroads, where the promise of high-tech jobs and energy independence championed by Radiant Industries collides with a wave of community doubts and tough legislative hurdles.

As the California-based startup pushes to establish its microreactor manufacturing facility, some residents and lawmakers have become increasingly vocal about critical questions surrounding nuclear waste storage, potential environmental impacts and the project’s lasting effects on this quiet Wyoming community.

Supporters view the plan as a generational opportunity aiming to create high-paying local jobs and diversify Wyoming’s energy economy by leveraging the state’s status as the nation’s largest uranium producer. Radiant’s Kaleidos units are designed to be factory-built, self-contained fission reactors, roughly the size of a standard shipping container, using helium gas for cooling and TRISO fuel. The company wants to build its plant north of Bar Nunn to handle the entire Kaleidos lifecycle, including assembly, fueling and testing, aiming to start deliveries by 2028.

However, the ambitious plan has sparked intense debate, revealing divisions among residents and state officials about safety, financial responsibility and nuclear waste issues. At the heart of the debate is Radiant’s business model, which proposes temporary storage of spent nuclear fuel at its site. That conflicts with Wyoming state law on spent nuclear fuel storage, and critics worry the “temporary” solution could become permanent, making Bar Nunn a long-term storage location.

The core issue: Spent nuclear fuel storage

Radiant’s business model revolves around its Kaleidos microreactor, a 1-megawatt unit designed to provide power for diverse applications, including military installations, data centers and remote communities. A core component of the model, and a central point of contention, is Radiant’s intent to temporarily house spent nuclear fuel at the manufacturing site.

Under its proposal, after a Kaleidos unit has been deployed and its five-year fuel life has concluded, the reactor would return to the Wyoming factory for refueling. The used cores, referred to as “spent fuel,” would then be stored on-site in dry casks. Radiant Chief Nuclear Officer Rita Baranwal characterized the amount of used fuel per reactor as small, equating to “about two Walmart gas grill propane tanks.” She said the TRISO fuel used in Kaleidos reactors is ideal for dry cask storage, which the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission recognizes for its strong safety record.

“All nuclear sites across the U.S. are required to hold their spent fuel,” Radiant Senior Operations Manager Makai Cartman told the Casper Kiwanis Club on July 24. He added it’s a temporary solution to the lack of a permanent national repository for high-level nuclear waste. Yucca Mountain in Nevada, once a prime candidate for that repository, is no longer being considered, and the U.S. Department of Energy is now working through a siting process in search of host communities.

That temporary approach faces a direct challenge, though: Wyoming state law bans commercial high-level radioactive waste facilities unless a federal repository exists. The state allows spent nuclear fuel storage only if it was produced and used in Wyoming, a change made by lawmakers in 2022 in preparation for the TerraPower nuclear facility near Kemmerer.

State Rep. Bill Allemand, a fierce opponent of Radiant’s waste storage plans, said the company’s business model is “not lawful” under existing Wyoming statutes. He also told a state legislative committee Wednesday that a poll conducted on his behalf last week showed more than 70% of respondents did not want nuclear waste “in their backyards.”

House District 58 Rep. Bill Allemand, right, speaks with a Rocky Mountain Power representative about constituents’ concerns regarding a proposed rate increase at the Ramkota on Aug. 28, 2024. (Greg Hirst, Oil City News)

House District 58 Rep. Bill Allemand, right, speaks with a Rocky Mountain Power representative about constituents’ concerns regarding a proposed rate increase at the Ramkota on Aug. 28, 2024. (Greg Hirst, Oil City News)

Radiant Chief Operating Officer Tori Shivanandan confirmed to Oil City News that without an amendment to state law to allow nuclear reactor manufacturers to temporarily store spent fuel from their devices, the company will not be able to enter Wyoming and will be forced to seek another site instead.

“I’d just like to add that Radiant’s not in the business of storing spent fuel. We’re in the business of making microreactors for our military,” Shivanandan said, “so we don’t want the fuel on-site any longer than it has to be. And as soon as the interim storage facilities or the permanent storage facility are available, we will move the fuel. Storing spent fuel will cost us money.”

Critics worry that delays in establishing a permanent facility could mean “temporary” storage could last for decades, making Bar Nunn like other U.S. sites with scattered spent fuel. For many residents, the amount of spent fuel, regardless of size, is a serious concern due to its proximity to their homes.

“No nuclear plant belongs here. It’s nice they want to do this; just not in our backyards,” Bar Nunn resident Amber Sparks wrote in a July 18 letter to the editor published by Oil City News.

Efforts to change the law have faced setbacks. Two bills introduced in the recent legislative session — House Bill 16 and Senate File 186, which aimed to set requirements for nuclear fuel storage and to allow advanced nuclear reactor manufacturers to store high-level radioactive waste, respectively — failed in the House. In recent town halls and local meetings, opposition has come from state representatives, including Rep. Kevin Campbell of House District 62 and State Rep. Tony Locke of House District 35, the latter of whom stressed the need for more research on spent fuel storage safety.

“Of course, the nuclear waste,” Wyoming Secretary of State Chuck Gray said during his July 21 town hall in Bar Nunn. “We’re here in Bar Nunn, the epicenter of the debate, and I want to tell you and be very clear, nuclear waste is wrong for Wyoming.”

Wyoming Secretary of State Chuck Gray speaks Monday, July 21, 2025, at The Hangar in Bar Nunn. (Nick Perkins, Oil City News)

Wyoming Secretary of State Chuck Gray speaks Monday, July 21, 2025, at The Hangar in Bar Nunn. (Nick Perkins, Oil City News)

With the Wyoming Freedom Caucus — now the majority in the state legislature — also publicly taking an anti-nuclear waste position, the path for Radiant to change the law may have become much harder.

“We support homegrown energy, not out-of-state waste subsidized to the tune of $25 million in taxpayer dollars,” the WFC said in a July 24 statement, referencing a $25 million Wyoming Business Council grant sought by the Casper/Natrona County Economic Development Joint Powers Board for infrastructure development, including sewer, water and a new public road that’s intended not only to benefit Radiant but also to attract other companies.

Radiant has said it has the money to build the infrastructure itself, but also said the grant factored into its decision to select the site. Justin Farley, CEO and president of Advance Casper, said the grant money was not sought by Radiant, but was instead offered by the Wyoming Business Council.

Campbell argues that allowing a nuclear waste storage exception would create a dangerous precedent, possibly transforming Wyoming into a “dumping ground” for nuclear waste from “anywhere on the globe” and putting unfair burdens and risks on state residents. Some outspoken residents share that concern.

“Once a reactor and storage infrastructure are in place, it is much easier to expand the scope to accept waste from other projects or companies,” Mitchell Groskopf wrote in a May 13 letter to the editor published by Oil City News.

In the national search for a permanent repository, Baranwal said some communities are open to hosting consolidated interim storage sites, often attracted by hefty financial incentives. However, for communities like Bar Nunn, the concern that “temporary” storage could become “permanent by default” is a major worry.

“My understanding is, too, that only a small number of our legislators want to bring in spent fuel from other states,” Judy Jones said during a July 22 Bar Nunn Town Council meeting. “What if we end up being like one of the 10 storage facilities that the United States is looking for or like a Yucca Mountain program?”

Community concerns beyond storage

Beyond the issue of where to store spent nuclear fuel, area residents have shared many concerns at town halls and local meetings about Radiant’s plant. Their worries include safety, environmental impact, openness, financial responsibility and direct effects on the community.

Safety and environmental concerns are the most frequently discussed issues for residents, who have asked about possible accidents, fires, water issues, high-energy impacts or even attacks on the facility. They’re also anxious about whether the community is ready for leaks or other emergencies.

“If it goes off within 10 miles and the people outside are exposed to anything like that, what are we going to do when we get an alert on our phone and it says everything outside is radioactive and we’re watching our kids play in the front yard?” Bar Nunn resident Alex Sherrow asked the Town Council during its July 22 meeting. “If an evacuation was needed, we don’t have to worry about looking at our kids in the front yard and noticing later, because of radiation exposure, their hair, their fingernails are going to fall out from a terrorist attack or something like that.”

Mike Newquist, a resident of Bar Nunn who often speaks at town halls and addressed concerns with the Natrona County Board of Commissioners, talked about shielding as an indication that a nuclear facility and its product transportation would be unsafe.

“I pity the guy, like me, that might have to work on [the vehicles that will be used to transport the microreactors], unsuspecting that, ‘Oh man, I’m getting irradiated right now while I’m underneath this trailer working for the next five to 10 to 12 hours,” Newquist said during Allemand’s July 24 town hall. “They refuse to talk about shielding. They will not talk about the shielding of these things. They refuse to. Why? It’s a basic question.”

Some residents feel Radiant often refers questions to the NRC or deflects them instead of answering them directly. At a town hall in Bar Nunn on June 14, community member and Natrona County School District 1 Trustee Jenifer Hopkins asked what residents should do to prepare for a possible leak or emergency. When Radiant Director of Operations Matt Wilson discussed safety, attendees said he was not addressing the question. Wilson then said Radiant would create plans for handling disasters.

Another concern is the long-term financial responsibility for waste storage. Residents are worried about who would pay for storage if Radiant fails, especially since the danger of spent fuel lasts much longer than the 40-year recertification period for dry casks. Radiant’s representatives say the company must hold a bond, and the Price-Anderson Act offers extra insurance coverage up to $500 million, with potential for another $15 billion from taxpayers for health, property and environmental damages.

The site’s proximity to the town and its possible effect on property values have been raised as concerns as well. Residents are asking why Radiant picked a location so near the town when there is plenty of open land available further away.

“I’m not anti-you,” a resident said during Radiant’s July 14 town hall, “but I prefer that you build it, like, 10, 20, 30 miles out of town.”

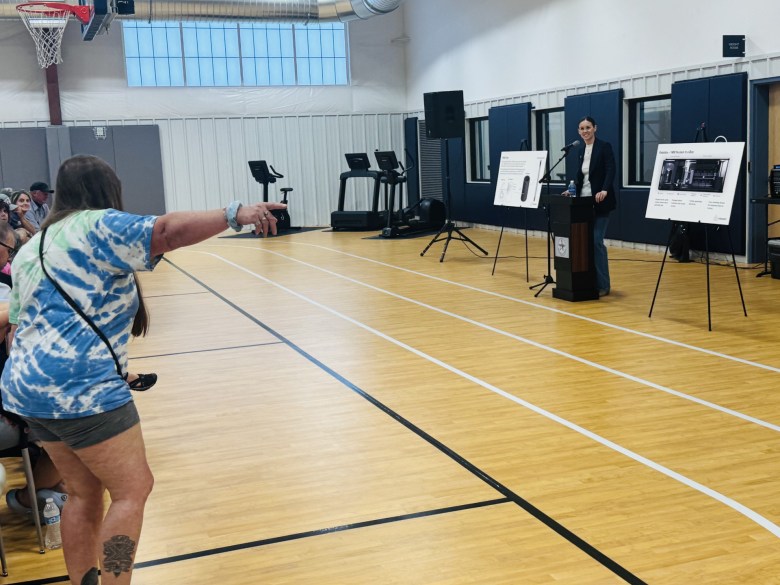

Chief Operating Officer Tori Shivanandan speaks with Bar Nunn residents on Monday about the company’s plans. (Nick Perkins, Oil City News)

Chief Operating Officer Tori Shivanandan speaks with Bar Nunn residents on Monday about the company’s plans. (Nick Perkins, Oil City News)

Some residents, like Susan Martin, worry that attracting high-income residents for the new industry could drastically hike property tax valuations, making it difficult for long-term residents to afford their homes.

With each town hall Radiant has hosted, views have reportedly turned more negative, though many feature the same speakers repeating their concerns or heckling the company’s representatives. In the political scene, Allemand has emerged as perhaps the fiercest critic, arguing that the project provides “no benefit” for Natrona County or Bar Nunn, especially when weighing the potential costs against predicted job creation. He’s also questioned Radiant’s job estimates and the cost-per-job analysis.

“Radiant says that within 10, 15 years, we’re going to have 250 people working out there, and we know that number is exaggerated so that they can get it through the Business Council,” the representative said, estimating closer to 100 jobs, with some potentially based outside of Wyoming.

Proponent, company rebuttals and reassurances

Bar Nunn Mayor Peter Boyer has become a strong supporter of the project. He said he learned about the nuclear industry by researching, consulting experts and visiting the Idaho National Laboratory at his own expense, which eased his concerns and assured him of its safety.

Boyer sees the project as an important opportunity for the town’s growth and prosperity. Likewise, Bar Nunn Councilor Dan Sabrosky, who also visited the laboratory, was initially doubtful but now thinks nuclear energy is the safest option. He criticizes what he terms “controlled Townhalls” and “misinformation” meant to frighten people.

Radiant, addressing safety and environmental concerns, has touted the design and strict regulatory oversight by the NRC for the Kaleidos microreactors and the dry cask storage of spent fuel. Baranwal said Kaleidos uses a safe “gobstopper”-like nuclear fuel, encased in ceramic layers designed to prevent meltdowns even at extreme temperatures. Unlike traditional reactors, the microreactor cools with non-radioactive helium gas and has an automatic shutdown system that enables natural, air-based cooling due to its compact size, Cartman said.

TRISO fuel particles are made up of a uranium, carbon and oxygen fuel kernel that’s encapsulated by three layers of carbon- and ceramic-based materials to prevent the release of radioactive fission products. (U.S. Department of Energy rendering)

TRISO fuel particles are made up of a uranium, carbon and oxygen fuel kernel that’s encapsulated by three layers of carbon- and ceramic-based materials to prevent the release of radioactive fission products. (U.S. Department of Energy rendering)

Radiant says its facility, fuel storage area and transport methods will be built to endure natural disasters and accidents, with shielding used in the reactors and areas where nuclear work is conducted. Cartman added that the manufactured reactors will not operate until they are connected at customer sites.

Daniel Thomas, a department manager at INL Used Fuel Management, told Wyoming lawmakers in May that dry cask storage has a strong safety record, with “zero release of radiation” in nearly 40 years in the U.S., according to WyoFile, adding that there have been “zero accidents” during transportation over millions of miles. While a 2016 presentation by Donna Gilmore, founder of San Onofre Safety, raised concerns about canisters leaking or cracking and advocated for thick-wall casks over thin-wall, the NRC says that since the first casks were loaded in 1986, dry cask storage has not released any radiation that affected the public or contaminated the environment.

The NRC estimates the radiological risks of transporting spent nuclear fuel as very low — often four to five times lower than natural background radiation — and has not identified any likely truck accident scenarios that could result in the release of radioactive materials.

Discussing the risks and the project in interviews with Oil City News and during town halls and government meetings, Radiant representatives have maintained the company’s commitment to transparency.

“We know the details of what we’re doing and we want to be able to share as much as we can,” said Ray Wert, Radiant Industries’ Vice President of Communications and Marketing. “We are very interested in continuing to be transparent and continue to answer literally any question that comes our way.”

That includes discussing why Radiant wants to be so close to Bar Nunn. Shivanandan said there are several reasons: to meet NRC distance rules for its minimal fuel use, to encourage community involvement, to shorten employee commutes and to lower utility costs.

Radiant’s technology is selected to be the first tested at INL’s DOME facility in 50 years, with a test deadline of July 4, 2026. That will mark a key step toward commercial use and a response to President Donald Trump’s executive orders for new reactor tests.

The economic benefits are a cornerstone of the project’s appeal to supporters. Radiant expects to create 70–80 jobs, growing to about 230–250 local jobs as production increases to 50 reactors per year. Company executives say they anticipate 90% of the jobs would be filled by local hires from Wyoming.

“I’ll continue to evaluate it based upon the information I have, but the information I have up to this point is that this is a legitimate, viable project that can be beneficial to our community for generations, and so in that respect, I’m going to keep an open mind about it,” Commissioner Peter Nicolaysen said during the Natrona County Board of Commissioners meeting June 17.

During that meeting, the commissioners lent their support to the Economic Development Joint Powers Board’s application for a $25 million state grant from the Wyoming Business Council.

A future in the balance

The Wyoming Joint Minerals, Business and Economic Development Committee met July 30 to discuss a draft bill that, if passed by the Wyoming Legislature in 2026, would specifically allow for Radiant’s business model of storing spent nuclear fuel within Wyoming, provided the device it’s used in is manufactured in the state.

After over seven hours of discussion with speakers including Allemand, his fellow state lawmakers, Radiant representatives and residents and leaders from Bar Nunn, Casper and Gillette presenting arguments for and against the bill, the committee postponed a decision on sending the draft to the full Legislature for the 2026 session.

Oil City News reporters Tommy Culkin, Nick Perkins and Garrett Grochowski and WyoFile contributed to this report.

Disclosure: Radiant Industries is an advertiser with Upslope Media, an agency owned by Oil City News owner and publisher Shawn Houck. Upslope Media clients play no role in Oil City News’s journalism.

Related