As hidebound Marxist regimes in eastern Europe were toppled at the end of the Cold War, many interpreted Ion Iliescu as the great communist survivor. To others he was simply an exemplary exponent of realpolitik after deposing the megalomaniac Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and ordering his execution on December 25, 1989. Thereafter, Ceausescu’s former propaganda chief balanced old-school authoritarianism with the playbook of liberal western democracy, although how truly democratic his three presidential terms were is still a matter of much debate.

With a largely poor and agrarian population and little economic development as a result of Ceausescu’s disastrous policies, Romania’s transition from totalitarianism was fated to be different from the “velvet revolution” happening at the same time in Czechoslovakia, which was led by the philosopher and intellectual Vaclav Havel.

When it became clear on December 21, 1989, that Ceausescu’s authority had been fatally breached after he was drowned out by protesters while speaking at a mass rally, the country descended into bloody chaos in which more than a thousand people were killed.

More than a thousand people were killed as anti-communist forces fought against Ceausescu’s regime in December 1989

JOEL ROBINE/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Perhaps a communist establishment figure who had been discredited by Ceausescu was the best that could be hoped for in a country where the army and the secret police remained powerful forces unready to cede power to revolutionaries.

Iliescu’s modern-day revolutionary credentials were based on the fact that he had lost his place as court favourite in Ceausescu’s regime in 1971. Opposing Ceausescu’s attempts to create his own cult of personality after a visit to North Korea — where the “dear leader” Kim Il Sung was a demigod whose divinity was attested by tearful devotion and monumentalist architecture — Iliescu had fallen from grace.

Eighteen years later and as part of an incongruous group of conspirators opposed to Ceausescu, Iliescu played his hand shrewdly, appearing on television to promise free elections, liberal economic reform and “liquidation of totalitarian state structures”. He soon emerged as the interim leader of what become known as the National Salvation Front (NSF).

Purist revolutionaries weren’t fooled. When Iliescu spoke at a rally in January 1990, crowds shouted “resign, resign”. Increasingly violent demonstrations the following month were dealt with in “the usual way”, prompting an editorial in The Times: “The threat of mob rule in Romania cannot be dismissed, and all governments have a duty to protect law and order. Yesterday’s response by Ion Iliescu, Romania’s acting president, far from achieving that goal is however calculated to foment further unrest …what lies behind the waves of demonstrations most of which have been remarkably peaceful, is the widespread suspicion that Romania has been cheated by a government itself largely composed of remnants of a dictatorial regime.”

In May 1990, Ilescu won 85 per cent of the vote to become Romania’s first freely elected head of state. Students gathered in the capital to protest the legitimacy of the election. In June that year, Iliescu brought thousands of miners to Bucharest by train from the Jiu Valley to disperse students who had been camping out in the capital’s University Square. At least five students were killed. Iliescu ludicrously characterised the protests as an “attempted coup by a force of extreme rightest elements”. The miners, he added, were a “powerful force for democracy”.

Disillusionment set in quickly. The former dissident and poet Ana Blandiana resigned from the NSF. Asked by The Observer in June 1990 if he were still a communist, Iliescu replied testily but did not give a definitive answer: “I’m getting really tired of this subject and I don’t think it is worth answering.”

He retained a tight grip on the press, and the national television station and state apparatus were largely manned by former communist officials who had served under Ceausescu. Iliescu strengthened his oligarchy by rewarding loyalty during the “restitution” of land taken by the former communist regime and privatisation of industry and state services that followed — even providing interest-free loans to favoured supporters. Romania would remain one of the poorest and most corrupt countries in Europe.

Iliescu was known in Romania as “Mr Smile” on account of his perpetual grin. He could be a witty and avuncular figure, but was unable to rid himself of the impression of something more sinister; an Observer profile in 1990 compared him to the gangster played by Bob Hoskins in the film The Long Good Friday. The journalist Anne McElvoy wrote of him in The Times: “Despite Mr Iliescu’s fluent English and eager smile, the whiff of the ancient regime clings to him.”

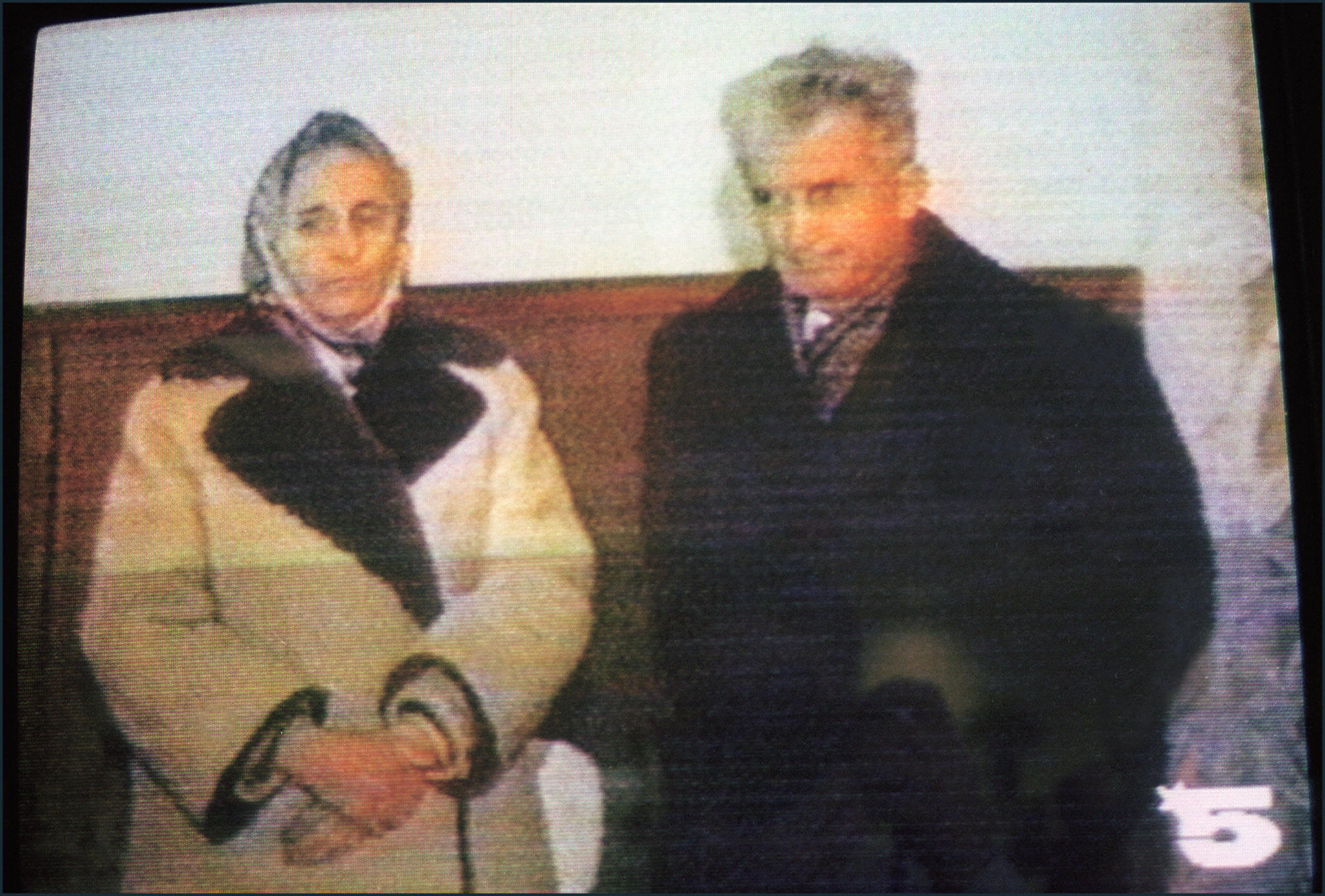

Elena and Nicolae Ceaucescu during their trial on December 25, 1989. They were executed together later that day

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Rather than a Polish-style “big bang”, Iliescu moved slowly towards economic restructuring. Not until his third presidency, from 2000 to 2004, did he initiate thorough reforms, succeeding in securing Romania’s entry into Nato in 2004 and the European Union in 2007. “Iliescu led the country’s transition to democracy without ever really fully embracing the changes necessary for Romania to become a full democracy,” said Vladimir Tismaneanu, a professor of politics at the University of Maryland. “He was neither a womaniser nor a lover of alcohol, and he didn’t get rich off the state. But his greatest vice was that he loved power too much.”

Ion Iliescu was born in 1930 in the Ilov district of Oltenita, in southern Romania. His paternal grandfather was a Russian Bolshevik who had fled to Romania to escape the tsarist police, and his father, Alexandru, a railway worker, had been a Romanian communist when the party was illegal, and died in prison in 1945.

Ion’s mother had abandoned the family when he was an infant and he was raised by his stepmother, Maria, and later by an aunt. He assuaged the emotional insecurity with communism. “I spent the first 16 years of my life fuelled by the idea that communism was going to bring happiness to the humble and would give them back their dignity,” he said.

Iliescu trained as an engineer, specialising in hydrology, and received degrees from the Faculty of Electrical Technology in the Polytechnic Institute in Bucharest and from the Moscow Institute for Energy. In 1955 he was employed as a design engineer at the Energy Engineering Institute in Bucharest. By now married to Nina, an engineer and expert on metal corrosion, who survives him, he joined the Romanian Communist Party in 1953 and served as secretary of the Union of Communist Youth (UCY) from 1956 to 1960.

In this capacity Iliescu travelled widely in the communist bloc. It strengthened rather than diluted his sense of Romanian nationalism and identity, which helped his political career in the early 1960s, when Romania struck out on an independent line in eastern Europe. In the early 1960s he rose through the ranks, and was elected a full member of the party’s Central Committee in 1965. He was minister for youth affairs from 1967 to 1971.

Iliescu was also a member of the Romanian parliament, where, in August 1968, he made an impassioned denunciation of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. It was music to the ears of Ceausescu. Further promotions followed and in 1971 “the Conducator” appointed Iliescu secretary of the Central Committee.

Iliescu fell from grace six months later. From 1971 to 1979 he was exiled to be secretary of local party organisations in the Timis and Iasi districts. In 1979 he was excluded entirely from the political arena and placed under close surveillance by the secret police. Iliescu cashed in on his professional qualifications and was made chairman of the National Council for Water Resources. But he was still too prominent a figure and in 1984 he was sacked.

Details of the anti-Ceausescu conspiracies of the 1980s are still obscure but it seems likely that Iliescu was involved in such groups from the middle of the decade. In September 1987 he published a full-page article in the weekly journal of the Romanian Writers’ Union calling for greater freedom of information and for social and political changes to overcome the prevailing inertia and alienation. Whether the NSF had been founded long before December 22 has never been established, but there is little doubt that it did not emerge in the heat of the revolution itself.

In October 1992, after a new constitution had been enacted, Iliescu was again elected president. When he lost the election in 1996 to Emil Constantinescu, he accepted the result and bided his time. With state apparatus still loyal to him, the strategy paid off. He was re-elected for a third term in 2000 and remained in power until his resignation and retirement in December 2004.

In 2018 Romanian state prosecutors charged Iliescu with crimes against humanity, alleging his culpability for the deaths of civilians during the revolution of 1989 by “approving military measures, some of which had an evidently diversionary character”, deliberately spreading misinformation, and taking advantage of the bloody chaos it caused to seize power. Court proceedings stalled, but last year prosecutors were reportedly to be preparing a new case. Iliescu called the charges “a farce”.

Ordering the executions of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu was one of his few regrets, because he acknowledged that it made him look no better. He attempted to write his own version of modern Romanian history with books including Revolution and Reform (1993).

Iliescu was proud of his legacy of overseeing what in his view was a difficult transition to democracy in Romania. Yet in 2006 a Romanian television station launched a vote to find the “100 Greatest Romanians”. Iliescu came in at 71st place, some way below Ceausescu. Whether history will ultimately be kinder to Iliescu as a realist and a pragmatist remains to be seen.

Ion Iliescu, Romanian politician, was born on March 3, 1930. He died of lung cancer on August 5, 2025, aged 95