It’s been a rough summer for Nicolai Tangen, the wealthy former hedge fund manager in London who came home to Norway to lead its huge sovereign wealth fund. The so-called Oil Fund, which Tangen has tried to demystify and even make “cool,” keeps growing but both he and it have sparked controversy along the way.

Nicolai Tangen still wears suits and ties from time to time, but has brought a more casual and “cool” style to the central bank’s Oil Fund offices. Now he needs to roll up his sleeves and fix a serious situation involving the fund’s investments in Israel. PHOTO: NBIM

Nicolai Tangen still wears suits and ties from time to time, but has brought a more casual and “cool” style to the central bank’s Oil Fund offices. Now he needs to roll up his sleeves and fix a serious situation involving the fund’s investments in Israel. PHOTO: NBIM

Right now the Oil Fund and Tangen are caught in an uproar, after the fund’s high ethical standards failed to halt highly profitable but questionable stakes in several Israeli companies. The Oil Fund’s suddenly problematic portfolio dominated headlines and news broadcasts this week, putting not only Tangen but also Norway’s central bank and the government on the defensive.

It’s especially embarrassing for the country because UN officials had already been questioning and criticizing Norwegian investments in Israeli companies. Both Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre and Finance Minister Jens Stoltenberg, who’s politically responsible for the central bank and its Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM) that runs the Oil Fund, had denied any “contributions” to Israel’s illegal occupation of the West Bank or alleged genocide in Gaza.

Now there’s no denying how the Oil Fund has profited on stakes in Israeli companies that help service and maintain Israel’s fighter jets, supply cameras for drones that drop grenades on Gaza and even own real estate on the West Bank. Stoltenberg has thus demanded a detailed rundown of the Oil Fund’s investments in Israel and a re-evaluation of them. The Oil Fund’s ethics council, on which the government has long relied to maintain Norway’s investment standards, has also been found to have been too weak in enforcing them: “We aren’t rigged for such extreme situations as Gaza,” its leader, Svein Richard Brandtzæg, told newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN) this week.

Some Members of Parliament still blame the Oil Fund’s own management, led by Tangen, for all the trouble that’s made Norway once again look like a war profiteer. Sales of Norwegian gas to Europe after Russia invaded Ukraine have raised such accusations before, now also its profits on Israeli investments. They’re likely to be sold off, with some recommending that profits realized be donated to good causes.

It’s all put Tangen, otherwise known for attracting attention, in an uncomfortable position, with some Norwegian politicians even calling for his resignation. He just won a second term as head of NBIM and claims to love his job, even though he took a huge cut in his own income when he took it on and faced lots of opposition along the way.

His casual style and insistence on being on a first-name basis has changed the culture at the Oil Fund and seems to have loosened it up, while profits keep rolling in. Tangen set the mood on his first day back in 2020, when he literally rolled into work on an electric scooter. Such scooters have since created massive controversy themselves, but with Tangen, it signalled a new era for the Oil Fund and at NBIM. It has since begun offering podcasts starring Tangen himself, a TV series on its inner workings and, not least, lots of controversy over what were perhaps overly friendly relations with Elon Musk. Tangen, who often uses the word “cool,” had promised Musk (through text messages he didn’t realize could be made public) one of the “coolest” dinners he’d ever eat but Musk didn’t want to come after the Oil Fund voted against his huge pay package.

The impressive interior of the Kunstsilo in Kristiansand, which houses Nicolai Tangen’s collection of modern art, has helped make it a huge attraction both for Norwegians and tourists alike. PHOTO: NewsinEnglish.no/Morten Møst

The impressive interior of the Kunstsilo in Kristiansand, which houses Nicolai Tangen’s collection of modern art, has helped make it a huge attraction both for Norwegians and tourists alike. PHOTO: NewsinEnglish.no/Morten Møst

Tangen, meanwhile, has donated his huge private collection of contemporary art to what’s now one of Norway’s major attractions, the so-called Kunstsilo art museum in Tangen’s hometown of Kristiansand, built inside old grain silos at the southern Norwegian city’s harbour. It’s been a huge success both with both Norwegians and visitors, winning lots of publicity in international publications and at home. Tangen and Norwegian artist Sverre Bjertnæs are also currently campaigning to maintain graphics as an art form. Tangen told newspaper Aftenposten recently that graphics are a more democratic form of art because they’re more available to the public and relatively affordable.

Tangen also remains an accomplished chef, wants NBIM employees to be happy and comfortable around him and travels constantly, not least since many of them are spread over offices around the world. The traveling, however, also caused him some public discomfort earlier this summer when his personal expense accounts generated more unwelcome headlines.

Both newspaper DN and business news service E24 reported how Tangen’s business class airline tickets, meals and hotels have cost NBIM around NOK 2 million (USD 200,000) since 2020, and then he claimed to have misunderstood the rules for reimbursement. When flights (mostly business class) involve an element of personal travel that makes airline tickets more expensive, the employee is supposed to pay the difference. Tangen ended up paying around NOK 230,000 back to NBIM, along with a “strong apology” for having misunderstood the rules: “When a mistake is made I take full responsibility,” Tangen told DN. “I’m very sorry this has happened.”

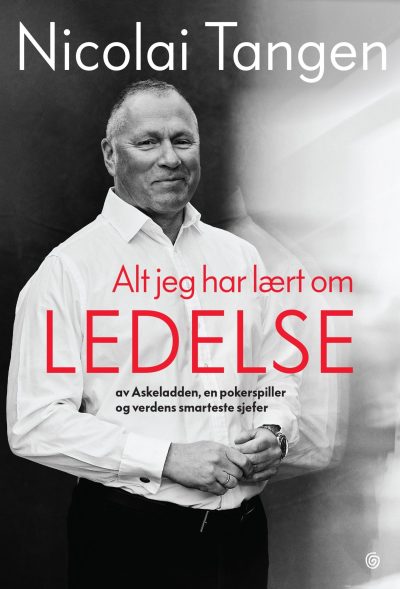

Just before all the headlines hit about the Oil Fund’s stakes in Israeli companies, E24 also reported that Tangen was about to release a book about leadership, what he’s learned from other leaders, and some of his experiences at the Oil Fund. He admits in the book that he had a “terrible” time during the conflict with Elon Musk, realized how “the system around me didn’t like this type of attention” and even feared his contract as NBIM chief wouldn’t be renewed.

Oil fund chief Nicolai Tangen’s new book, the title of which roughly translates into “Everything I have learned about leadership, from Askeladden (a mythical Norwegian character seeking his fortunes), a poker player and the world’s smartest chief executives.” PHOTO: Kagge Forlag

Oil fund chief Nicolai Tangen’s new book, the title of which roughly translates into “Everything I have learned about leadership, from Askeladden (a mythical Norwegian character seeking his fortunes), a poker player and the world’s smartest chief executives.” PHOTO: Kagge Forlag

“It would have been nice to say that I brushed it all aside … took it like a man … but the truth is that even though I held up during all press conferences and interviews, I was feeling terrible,” Tangen wrote in the book entitled Alt jeg har lært om ledelse (Everything I’ve learned about leadership). He credits central bank boss Ida Bache Wolden, who’s also his immediate superior, for calling him at home to see how he was doing. It meant a lot to him, he wrote, that his boss cared and offered support, as did many colleagues.

The book, which builds upon his podcasts called In Good Company, otherwise offers advice on how to deal with crises and how other chief executives have done so. He’s interviewed more than 100 business leaders in his podcasts, and felt a need to share what he’d learned from them. He also worries that many people with power in high positions are more keen to rule than to lead.

His book project wasn’t known and apparently meant to be a surprise. E24, however, got wind of it and went to extraordinary measures to read a copy that had been submitted by Tangen’s publisher (Kagge Forlag) to Norway’s state directorate for culture, in the hopes of including it in a state purchasing program. Then Tangen was subjected to more critical press coverage, when his publisher tried to halt E24’s news article about it. That backfired entirely and instead the book was released four weeks earlier, on Tuesday, the very day that news broke about the Oil Fund’s Israeli investments.

Reviews of the book have been mixed but Tangen has his supporters, including those who think he’s done a good job opening up NBIM and the Oil Fund’s activities to the public. The fund itself is hugely important in Norway, not only as a means of ensuring pensions for future generations but also as a source of funding for the state budget. Even though only 3 percent of the value of the fund can be spent in any given year (so as not to overheat Norway’s economy) the fund allows Norway to avoid budget deficits year after year. The amount of annual withdrawals was also reduced several years ago from 4 percent, since the fund had grown so much. It still ranks as among the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world.

Tangen certainly seems keen on continuing to run it, preferring to call it Pengelandslaget, a sort of national team committed to the goal of earning more money for Norway. Big money, with the fund worth NOK 20,318 billion, or roughly USD 2,032 billion, as this story was being written on Friday afternoon. He wants to keep his job after the recent rash of controversy around both him and the fund.

He also has his critics, but newspaper Aftenposten even editorialized on Thursday that the Oil Fund should continue to invest in Israeli companies, as long as they’re not involved in any violations of the rule of law or crimes against humanity. Without sanctions against Israel, any total pullout would be seen as political and that could be unfortunate. Better to boost the capacity and expertise of the fund’s ethics council, wrote Aftenposten, to recommend exclusion of companies directly involved in Israel’s war apparatus.

Norway’s Greens Party, the Socialist Left and the Reds have all called for pulling out all Oil Fund investments in Israel. The Greens also have called for Tangen’s resignation, but have little support for that. Finance Minister Stoltenberg has given the central bank, NBIM and its ethics council until August 20 to come up with a full overview and status of the Oil Fund’s investments in Israel.

NewsinEnglish.no/Nina Berglund