Is the global economy changing? This question was posed last week by Karl-Heinz Paqué, economist and chairman of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, in his column on the reforms in Argentina. This week, the question of whether the global economy is changing was answered with a resounding “yes” by the EU”s trade deal with the US. Paqué continues his in-depth analysis following what he sees as an epoch-making event.

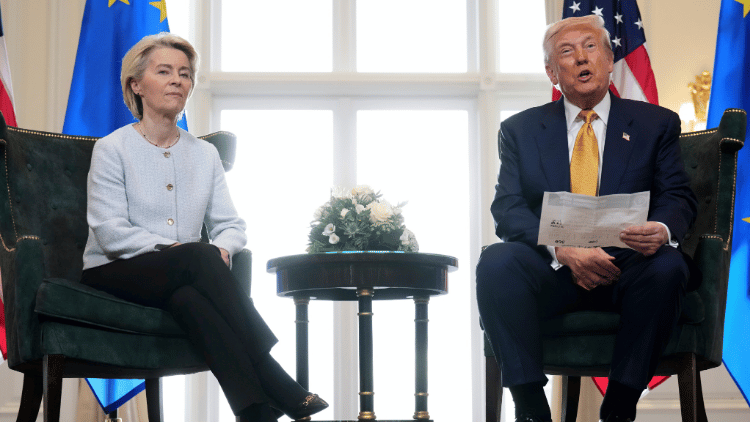

The latest trade agreement between the US and the EU – negotiated by Trump and Ursula von der Leyen – is a serious diplomatic defeat for the EU, the most serious in its trading history. The US is imposing a 15 percent tariff across the board, while the EU is not imposing any additional duties and is even reducing some tariffs on US imports. The declaration of intent to remove tariff protection in certain sectors (such as agriculture) on both sides is worthless with a negotiating partner like Trump. In addition, the EU is promising to import coal and gas from the US on a breathtaking scale and to invest in the US – incidentally, on behalf of its own private industry as part of a kind of planned economy “management without a mandate,” and this with a focus on energy sources that are considered “dirty” in Europe, thus massively contradicting the commitments and principles of its own energy policy.

The outcome of the negotiations could hardly be worse. It is an unconditional surrender by Europe. German EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (CDU) caved in completely to Trump’s threat to introduce a general tariff protection of 30 percent, apparently in agreement with German Chancellor Friedrich Merz (CDU).

Of course, Europe’s diplomatic weakness can be explained by more than the personal political failures of individuals. It is the result of the EU’s economic weakness. And that, in turn, has been developing and building up over two decades. There has been a consistent lack of an aggressive supply-side strategy to improve economic conditions in Europe – beyond a “Green Deal” that appeased the ecological conscience but did little to make Europe more competitive in the world. Only if this changes fundamentally will the EU have a chance of escaping the long-term decline of its prosperity and technological leadership. This change must begin as soon as possible. It will keep the EU busy for years, if not decades, alongside the (expensive but necessary) security and defense offensive that Trump recently forced Europe to adopt within NATO.

So, is Trump victorious on all fronts? Not at all. The American president is isolating his country in the vague, if not entirely unrealistic, hope that he can bring back good old industry to America, in a technologically modernized form, of course—at least that is the vision. This will fuel inflation in the short term and go completely wrong in the long term. The opposite of what is hoped for will happen, as is always the case with large-scale protectionist experiments. Tariff protection of 15 percent against the EU, 10 to 30 percent against the rest of the world, and 50 percent for selected industries such as aluminum and steel will drive even a large economy like that of the US into inefficiency and innovation weakness. Tariffs on this scale – the highest in the US since the temporary tariff peak of the infamous Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 – will massively reduce competitive pressure. If the tariffs remain this high, we will only have to wait two to three decades before the US follows the path already taken by many countries that have closed themselves off: stagnation and contraction.

So, does this spell the end of global economic integration, with a weak Europe and a closed-off US? Not necessarily. The new geopolitical and economic situation offers the countries of the Global South a unique opportunity to massively accelerate their own integration into the global economy. Above all, those nations that are already emerging economies or “middle-income countries,” i.e., those that already have a certain amount of economic power, have the necessary prerequisites for this. However, they need consistently liberal policies to achieve this. They must open up—through free trade agreements in almost all directions (except, presumably, Trump’s US, which does not want this at all). Latin American nations such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Uruguay may be the ideal candidates for integration in the medium term, as are Australia, Japan, Canada, South Korea, India, Indonesia, Thailand, and some countries on the African continent such as Kenya, Morocco, and South Africa. It is in the interests of a stagnating EU to reach out – the rapid conclusion of the EU-Mercosur agreement is a first test of this.

A new “globalization of the future”? You don’t have to be considered hopelessly melodramatic if you talk about this exactly 80 years after the end of World War II. For what is looming here is indeed an epochal turning point. The US is withdrawing as a liberal leading power for the foreseeable future and is closing itself off. Europe is preoccupied with itself, but at least it has the opportunity to finally implement radical internal reforms and restructure its global economic integration, less with the US and more with the Global South and democratic market economy partners from other regions of the world.