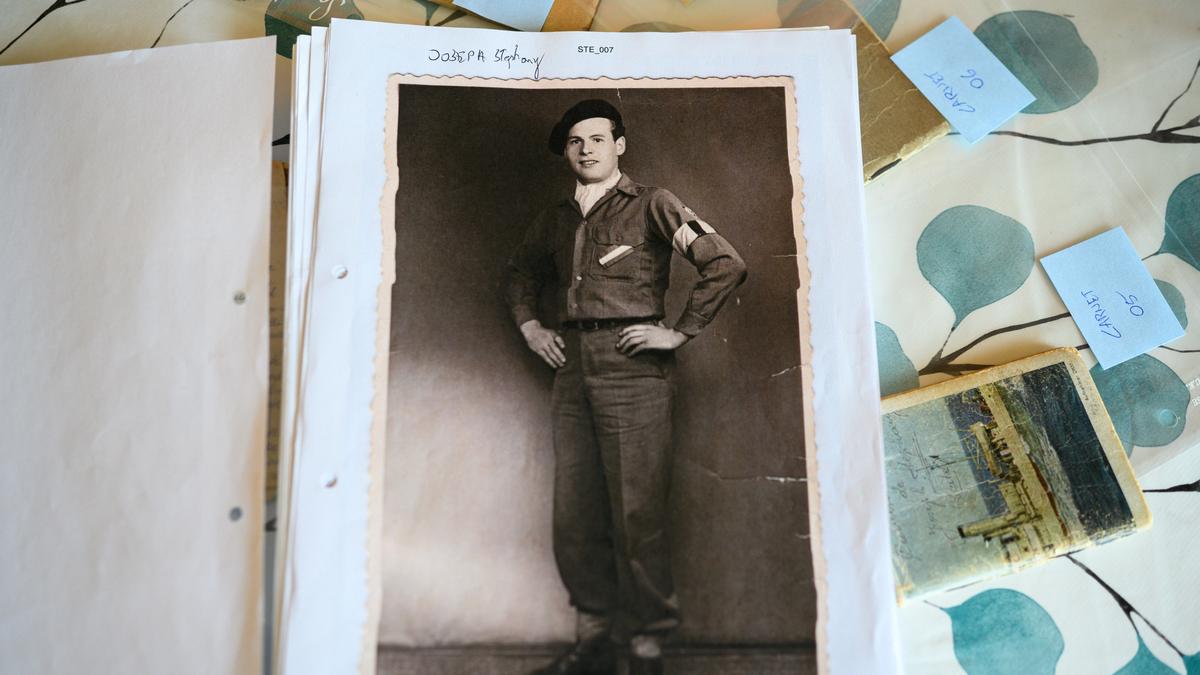

After Joseph Stephany’s death in 2009, his son Richard came across a bundle of notebooks, stitched together by hand. They contained his father’s diary from the time when he was an inmate in the Wehrmacht prison Fort Zinna in Torgau, eastern Germany. He was held there, threatened with execution, between March 1944 and May 1945, awaiting his sentence for being a deserter and resistance fighter.

It was the first time that Richard Stephany read his father’s story in his own words – written in French and in small, careful handwriting.

“J’ai eu de beaux rêves…” (I had beautiful dreams) reads an entry from 7 March 1945. “In one [of these dreams] I was in Boberstein, in another I managed to escape from prison…”

It’s a faint message of hope written in one the largest military prisons in Germany during the Second World War.

For Richard Stephany, son of Joseph Stephany, the publication of his father’s diaries is more than just an act of remembrance. It is also a reflection on totalitarianism and how one can rebel against it © Photo credit: Gilles Kayser

Fort Zinna was the central Wehrmacht prison and the seat of the Reich’s court martial. By 1945, more than 1,000 death sentences had been passed at the prison, including those of several Luxembourgers. There are 54 names on a list kept by Joseph Stephany entitled “Mes copains condamnés à mort” (My friends sentenced to death.) Fourteen of them are marked with a small cross.

Richard Stephany knew about these diaries while his father was still alive, but the son could not bear reading them during his father’s lifetime. He felt they were too intimate, too sensitive. Today, however, he is left with a number of questions to which he can no longer find answers.

From the volunteer company to the SS

The prison diary of Joseph Stephany, written in French in small, careful handwriting © Photo credit: Gilles Kayser

Joseph Stephany, born in 1921 in Huldange, grew up in simple rural circumstances. To give him a better education, his parents sent him to a convent boarding school in Marseille. As a result, he spoke and wrote fluent French, a skill he later used in his diaries in prison to distance himself from the language of the occupying forces.

He returned to Luxembourg in 1939. At the beginning of 1940, he joined the Luxembourg Volunteer Company with the aim of becoming a gendarme. After the German invasion in May of that year, this company was placed under German administration. It was quickly transferred to the SS, the Nazi regime’s elite paramilitary corps.

Joseph Stephany defended his time in the SS after the war, saying he did not join voluntarily but was forced. Like other young men in the volunteer company, he was likely threatened and pressured, his son believes today.

At the machine gun in what is now Ukraine

In the spring of 1941, Stephany was assigned to the 7th SS Volunteer Division “Westland”, a troop that was involved in the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany shortly afterwards. As a machine gunner, he fought on the front line in what is now Ukraine. On 17 September 1941, he was hit in the head by a shell fragment. “That must have been south of the Dnieper,” says his son.

A small piece of metal smashed through his skull, two centimetres from the top of his head. He suffered a second splinter wound to his temple. Stephany lost consciousness and when he woke up again, the right side of his body was paralysed.

Joseph Stephany’s police identity card issued in June 1940 © Photo credit: Gilles Kayser

But he had survived. After stops in Kriwoi Rog and Krakow, he was hospitalised in Prague. His recovery took six months. The injury left a deep, V-shaped dent in his skull. At this time, Germany was still winning the war and there was still medical care available. “A year later, nobody would have picked me up,” Stephany later wrote laconically.

Also read:How a young Luxembourger escaped joining the Hitler Youth

Inner distance from the Nazis

After his release from hospital, he returned to Luxembourg. In the summer of 1942, Stephany deserted and joined the “Armée Secrète” (Secret Army) resistance movement in the Belgian Ardennes, in which Jean, Jacques and Josette from the Stephany family were already fighting. He took part in sabotage operations and helped to hide downed Allied pilots.

Now I am back from Germany, my life as an illegal is over, I am a free man again – and on this day I close my diary. Signed: Jos Stephany

Joseph Stephany

Member of the volunteer company, SS soldier and then resistance fighter in the Armée Secrète in Belgium

On 30 March 1944, his unit was betrayed after one such operation. Stephany and two other resistance fighters were arrested by the field gendarmerie in the Belgian Ardennes near Marche-en-Famenne. A first interrogation, then a night in prison, a cigarette, a meal and the next day the transfer to Namur. On the same day, Stephany began writing his diary.

Medals awarded to Joseph Stephany as a resistance fighter and member of the Armée Secrète in Belgium. © Photo credit: Gilles Kayser

“Mon Dieu!” (My God) is his first entry as the cell door closes behind him. Joseph Stephany begins what would become almost 14 months of prison life in Fort Zinna in Torgau, Saxony. The first few days are marked by uncertainty, hunger and prayer. Stephany is very devout. He meticulously describes his everyday life: the food, his fellow prisoners, conversations, thoughts and fears. A German in the cell shares a cigarillo with him and stories from the front.

By the end of the war, there will be six booklets: notes from the innermost thoughts of a political prisoner. Stephany’s texts revolve around fear and hope. They describe small gestures of comfort. They also contain memories of landscapes, dreams and family. At the same time, they document the systematic repression of the resistance through isolation, court judgements and executions.

The diary entries revolve around fear and hope, small gestures of consolation, memories of landscapes, dreams and family © Photo credit: Gilles Kayser

At the very end, the young man, who was once a member of the SS and was arrested as a deserter and resistance fighter, describes the last days of his imprisonment and his return to freedom: waiting for planes that ultimately never came, the improvised journey home by train through a destroyed Germany, crossing the border into France and finally, on 25 May 1945, his arrival in Luxembourg.

Also read:The death of the Léonard brothers, a family tragedy long shrouded in silence

He finds his homeland changed. The joy of survival is mixed with the pain of his brother Jean’s death. In a final sentence, he notes simply: “Now I am back from Germany, my life as an illegal is over, I am a free man again – and on this day I close my diary. Signed: Jos Stephany.”

Eighty years after the end of the war, his son Richard regrets that he cannot tell his father’s story in any more detail. For him, however, publishing the diaries in book form is more than just an act of remembrance. It is a reflection on how young men sometimes submit to totalitarian systems, but sometimes also assert themselves and how they find the courage to resist.

The book “Als junger Luxemburger in NS-Haft – Die Tagebücher von Joseph Stephany” (A young Luxembourg in a Nazi prison – The diaries of Joseph Stephany) was produced with the support of the Oeuvre Nationale de Secours Grande-Duchesse Charlotte and the Federal State of Saxony, among others © Photo credit: Gilles Kayser

The diaries are published under the title “Als junger Luxemburger in NS-Haft – Die Tagebücher von Joseph Stephany” by Richard Stephany, published by the Musée National d’Histoire Militaire and Erinnerungsort Torgau / Stiftung Sächsische Gedenkstätten, 280 pages, €27. Can be ordered in the online shop of the Musée National d’Histoire Militaire (www.mnhm.net).

(This story was first published in the Luxemburger Wort. Translated using AI, edited by Cordula Schnuer.)