The Allied cracking of Germany’s Enigma machine reshaped the course of World War II. Now, Europe is racing to harness a far more powerful code-breaking tool — the quantum computer, but it’s running short on the software needed to do it.

In the near future, the quantum computer holds the power to impact sectors from defence, to health care, chemicals and more with hardware already more and more accessible.

But cracking the physical infrastructure is one thing. Cracking on with the software is another entirely.

Experts, investors, and policymakers are increasingly paying attention to the code locked inside quantum computers – technology that could one day break cryptographic algorithms rapidly and upend the world’s digital systems as we know them.

Though an array of developers across Europe work on hardware, the EU needs to shift focus to software development, says quantum engineer and researcher Olivier Ezratty.

“If Europe overlooks the strategic importance of quantum software development, it risks falling behind in the global race,” he said, adding that the European Commission’s current quantum strategy is focusing too heavily on hardware.

What is quantum, and why should we be good at it?

While classic computers use millions of electrons to process information as binary bits – either 0 or 1 – quantum computers use single particles like atoms or photons as quantum bits, or so-called qubits, which can exist in multiple states at once.

This may sound abstract, but is a fundamental difference. In practice, it means quantum computers can solve some problems far more efficiently than conventional computers – some requests that might take a conventional computer years could be solved within minutes or hours with a quantum computer.

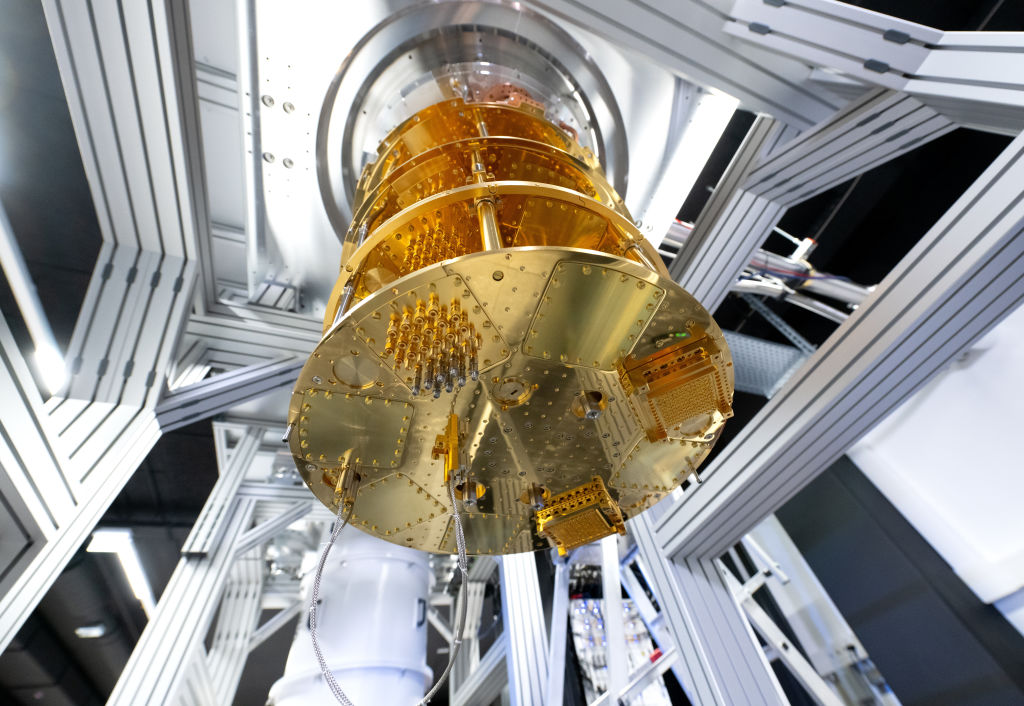

Across the EU, multiple companies are developing hardware at every level of the tech stack: Germany’s Toptica provides cutting-edge photonic lasers, while Finland’s Bluefors is a leading supplier of dilution refrigerators – essential for cooling quantum systems close to absolute zero, a critical requirement for quantum computing. Denmark’s Sparrow Quantum produces photonic chips, and French startup Alice & Bob has demonstrated its ability to develop error-resistant quantum computing.

In addition to that, Finland’s IQM is famous for its pioneering of quantum computers. French cloud providers OVHcloud and Scaleway have linked several quantum startups emulators to their platforms, which allows users to develop quantum software at a much lower price point. The cloud operators are expected to offer access to real quantum computers soon.

But for Ezratty, these private initiatives are not enough to spur European quantum development and make it competitive globally.

In short: European companies are developing all you need for your quantum hardware – from chips to cables to cloud access – but the crucially needed software development that is a must to get a quantum computer off the ground is falling short.

Across the pond, US tech giant IBM offers an open source software kit, Qiskit, designed to help developers learn quantum programming. Through this, IBM is not only building a talent pool familiar with their tools but fostering early ecosystem integration.

Others such as QC Ware (US), Riverlane (UK), Classiq (Israel), and Horizon Quantum (Singapore) are developing their own software tools, too.

Where is the EU standing in comparison?

For now, Europeans have done a good job in financing quantum startups. However, this trajectory might eventually come to an end, especially when one looks at funding beyond Europe’s borders.

For now, the majority of the bloc’s quantum tech investments come from public funds, 51% to be exact, according to a 2024 McKinsey study. In comparison to just 2% in the US and 10% in the UK.

In addition to that, unlocking private investment proves historically difficult for companies in the EU: Between 2001 and 2023, the UK attracted 1.36x more private funding into quantum tech than the EU as a whole, for example.

The European Commission has acknowledged a financing gap, too. “[P]rivate investment is becoming the key differentiator between success and failure,” the Commission’s quantum strategy, published last month, reads.

Some EU quantum startups managed to raise significant amounts, though. IQM has pulled in a total of €200 million, Pasqal and Alice & Bob have raised €140 million and €130 million respectively.

But looking at funding rounds across the Atlantic, the European rounds are dwarfed in comparison. US-based QuEra closed a $230 million funding round in February, for example, while Maryland, US-based IonQ pulled in $360 million.

“For companies that are now at the growth stage, the EU lacks specialised venture capital funds that can act as lead investors in later stages funding rounds,” Olivier Tonneau, founder of Quantonation, a French early stage quantum investment fund, told Euractiv.

Ideas to scale up investment include getting the EU to ease rules for banks, insurers, and pension funds to unlock more quantum scale-up financing – something the Commission has been indirectly considering after prompting from lobbyists.

(nl, jp, vib)