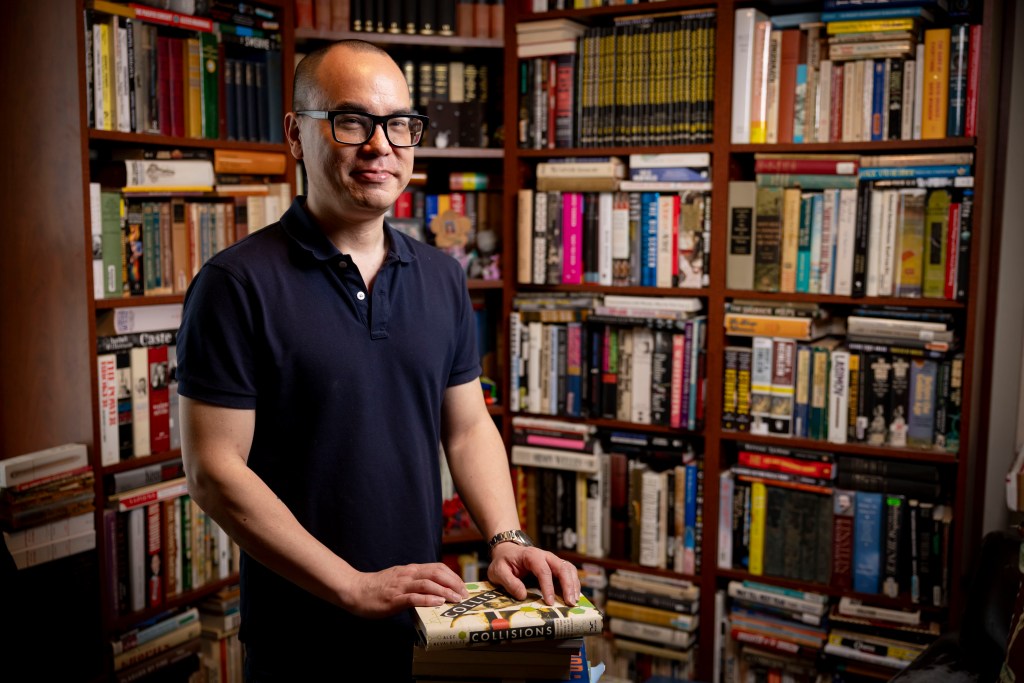

Luis W. Alvarez, physicist, genius, conspiracy debunker, military hawk, Zelig, University of Chicago dyspeptic, to cut to the chase, was not a very pleasant man. He was not especially liked by colleagues. It’s hard to tell if he was even liked by his kids. And so, for Alec Nevala-Lee of Oak Park, who has become an underrated biographer of Great Jerks in Science, Alvarez was perfect.

Nevala-Lee’s previous biography was on Buckminster Fuller, architect, futurist, longtime professor at Southern Illinois University, but also an infamously obtuse, inscrutable mansplainer’s mansplainer — his lectures seemed to go on for days. Before that, Nevala-Lee wrote “Astounding,” a harrowing account of the men behind mid-century science fiction, particularly editor John W. Campbell, who could be described charitably as fascist.

His next book, already in the works, is about those lovable scamps behind the RAND Corporation, the most despised think tank in history. Am I nuts or do I see a pattern here?

“No question!” Nevala-Lee said the other day, getting a little loud in his neighborhood library. “I like intelligent people who succeed in one field only to try and apply those skills elsewhere and decide that they should convince the world that only they have the answer to certain problems.”

At the risk of playing pop psychologist, I asked a natural follow-up:

Is that you, too?

“I mean, uh… I get it.” He smiled. “Am I a reasonably intelligent person who thought a lot about where to apply their skills? Sure.” I asked this because he attended Harvard University and left with a degree in classics and an over-confident idea that knowing the classics was really the only way to become a writer. So when his fiction-writing career stalled before it could get started, he decided to reinvent himself. He developed a talent for writing quite accessible histories of the boorish.

The boorish, but brilliant.

As Nevala-Lee explains in “Collisions: A Physicist’s Journey From Hiroshima to the Death of the Dinosaurs,” his surprisingly breezy new history of Luis Alvarez, the Nobel laureate and occasional Chicagoan was pragmatic, for better and for worse. He preferred to work where his skills would get noticed by the widest number of important people — smartly leading to funding and fame. Alvarez had, Nevala-Lee writes, taste when it came to science. Meaning, eventually, after years of frustration in Hyde Park, he knew how to pick projects that “were both achievable and important.”

Which is an understatement.

Alvarez learned how to position himself at the heart of the 20th century.

He helped develop radar during World War II. He worked on the creation of the atomic bomb with Enrico Fermi and J. Robert Oppenheimer. He flew behind the Enola Gay as a scientific observer while it dropped the first nuclear weapon on Japan. In fact, Alvarez’s bubble chamber, the project that would earn him a Nobel, may have been his least publicized work: a pressurized chamber to help scientists study particle behavior. It was groundbreaking, though not as thrilling as proving — using a bunch of watermelons and a high-powered rifle — why the Warren Commission was probably correct about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. In Alvarez’s last decades, as if knocking out a little extra credit, he even gave us the answer to a mystery we all know the answer to now: He explained how a planet ruled by dinosaurs could go extinct nearly overnight.

But … he was also something of a bootlicker.

“Alvarez knew how to cleave to power,” Nevala-Lee said. “In a way I find interesting. The contrast to Oppenheimer is real, because Oppenheimer, equally brilliant, spoke his truth as he saw it.”

He came to regret his role in creating nuclear weapons, so at the peak of McCarthy-era paranoia, his loyalty to the government was doubted and the head of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory had his security clearance revoked.

Alec Nevala-Lee’s new book “Collisions: A Physicist’s Journey from Hiroshima to the Death of the Dinosaurs,” in his Oak Park home office on June 9, 2025. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Alec Nevala-Lee’s new book “Collisions: A Physicist’s Journey from Hiroshima to the Death of the Dinosaurs,” in his Oak Park home office on June 9, 2025. (Brian Cassella/Chicago Tribune)

Alvarez, meanwhile, “was very careful about alienating people he needed to get stuff done,” Nevala-Lee said. “In fact, and this is important, he doubled down and felt the solution to the Soviet problem was definitely a thermonuclear bomb. Alvarez would even become one of those people who was all for mutual assured destruction. Oppenheimer was not. Alvarez had such a high opinion of his own intelligence that when he sees someone equally bright, like Oppenheimer, opposing him on a fundamental point, he assumed it couldn’t be he’s wrong — no, Oppenheimer must be compromised. I don’t know if he really believed that for sure, but I think so: Alvarez saw it to his advantage if Oppenheimer could be neutralized. He was causing problems, and Alvarez’s work would go smoother if he was out of the way.”

In the end, ever an opportunist, Alvarez testified Oppenheimer was loyal to his country, yet wrong on nukes. Not the profile in courage that makes for Oscar biopics. (Indeed, in Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer,” Alvarez is mostly on hand to say Germans just split the atom. Then he’s gone from the picture. Alvarez, whose career was just getting started in 1939, wouldn’t have been pleased.)

To make matters worse, egads — Alvarez didn’t seem to be a big fan of Chicago.

Scientist Luis Walter Alvarez with a radio transmitter used in a radar ground-controlled approach system built to help guide airplanes to land. (AP)

His ex-wife lived here with his ex-mother-in-law. During the development of the bomb, while traveling constantly between MIT and Los Alamos, he would call Chicago his “decompression chamber,” but after working for a while at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, he felt rudderless and assumed all of the interesting science was being done elsewhere. He became something of a legend around Hyde Park — “high on my list of mythological figures,” is how one scientist at University of Chicago described him — but Alvarez himself complained bitterly of his undergraduate education at the school, a place where, he said: “Most of the graduate students didn’t understand any quantum mechanics, largely for the reason that the professors had just learned it themselves.”

He sounds, in many ways, I told Nevala-Lee, like the archetypal UC student.

How so, he asked.

Arrogant, awkward, questioning yet has all the answers; inquisitive yet careerist.

“I mean, that describes Alvarez,” Nevala-Lee said. “I think of him now as someone who understood how to get things done. But he was abrasive, didn’t treat subordinates well — it was a problem. He would have gotten more accomplished if people didn’t feel personally attacked by him so much. He assumed if you were in physics at his level, you get this treatment. Can’t take it, find another field.”

Tack on a whimsical side — a study of UFOs, a study of pyramids, a genuine love for the science of the Superball by Wham-O — and Alvarez even sounds like a descendant of, well, Elon Musk. Nevala-Lee can see it. He was once enthralled himself by “the American idea of visionary genius.” Nevala-Lee is 45 now, though younger, “I had an exaggerated sense of my own abilities. I thought of myself as someone who could enter the world and solve its problems myself. Elon Musk was that guy about 10 years ago. I’ve since become pretty skeptical of this idea of a visionary genius. I don’t know now if they ever did exist. Deep down, our figures like this, they all have the same problems.”

By the way, since you’re probably wondering, for the record, Nevala-Lee is a nice guy.

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com

Alec Nevala-Lee will discuss “Collisions” on Monday, Aug. 18, at the Harold Washington Library, 400 S. State St. The event begins at 6 p.m. and is free.