Five years on from a fraudulent election organized by the Lukashenka dictatorship, Belarus’s best-known opposition leader-in-exile believes there’s still hope.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, an opposition candidate in the 2020 presidential election, wants to emphasize that the August anniversary marks more than the theft of a popular vote; it is also the five-year anniversary of Belarus’ peaceful, popular uprising. Following the announcement of Aliaksandr Lukashenka’s victory, and Tsikhanouskaya’s widely supported declaration that it was falsified, the largest demonstrations in Belarusian history erupted nationwide. More than 65,000 people were jailed, and many protesters were beaten.

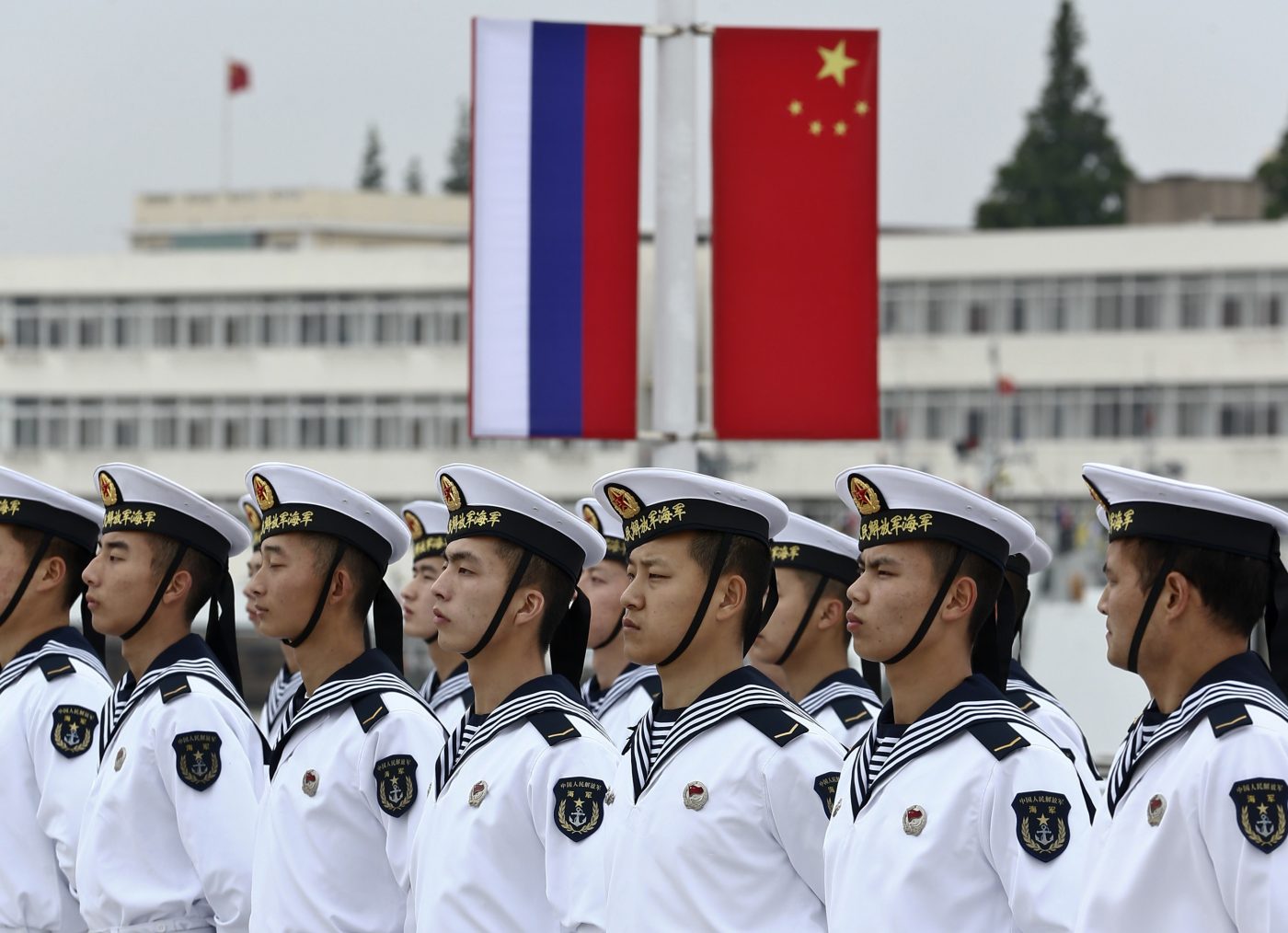

The outlook, since then, has been bleak — Lukashenka is now an even closer ally of Vladimir Putin and supports his invasion of Ukraine, among other things by providing military bases and prisoner-of-war camps. Belarusians live under repression and in fear, and dissenters are rounded up every day.

But all is not lost, and Tsikhanouskaya described a possible path forward. The Belarusian opposition continues to work in exile and hopes to keep resistance alive. Belarus will need help from the outside, she says, and continued US and European Union (EU) support remains critical.

“The aspirations that people showed five years ago when they wanted democracy, freedom, a different political course for their country — this has not expired,” said Katia Glod, an independent analyst and political risk consultant.

The opposition also seeks to emphasize that aiding democratic efforts in Belarus fit into a broader regional policy of opposing the Kremlin’s imperial expansionism. “Belarus isn’t always on the top of the agenda, but as long as it remains under Putin and Lukashenka, it will always be a threat to Ukraine, NATO, and regional stability,” said Tsikhanouskaya. A long-term hope for Belarusian democratization is that it could incite a similar movement in Russia.

Western allies ought to turn up the heart on the Lukashenka regime instead of engaging him, according to the 42 year-old former teacher. “For years, the West tried to play with the Lukashenka regime, which only emboldened him.” Belarus’s opposition has gained diplomatic ground, though, developing formalized relationships with the EU, Canada, and the UK, and maintaining a strategic dialogue with the US.

The opposition hopes allies can help push change in Belarus by adopting a more assertive policy, including options such as sanctions, political isolation, or non-recognition. Tsikhanouskaya also suggested the appointment of a US special envoy to Belarus similar to retired Lt. Gen. Keith Kellogg, who serves as the special envoy to Ukraine and Russia.

Get the Latest

Sign up to receive regular emails and stay informed about CEPA’s work.

Outside pressure has clearly had some effect — Tsikhanouskaya’s own husband was released from prison after a meeting between the US Special Envoy for Ukraine and Russia, and Lukashenka. But over 1,100 political prisoners remain.

As a shared policy objective between the West and the Belarusian opposition, the war in Ukraine in particular offers two opportunities to the pro-democracy movement in Belarus.

First, Russia’s war of aggression is generally unpopular among Belarusians. According to a Chatham House survey, only one-third of Belarus’ population supports the war in Ukraine, and Glod notes only 4% support direct Belarusian involvement on Ukrainian soil. Any escalation of Belarusian involvement, combined with domestic discontent, might add fuel to the opposition’s mobilization efforts.

Second, any outcome negotiated between Russia and Ukraine will affect Lukashenka’s strategic position. A favorable outcome for Ukraine could also be an opportunity for the Belarusian opposition. “If peace is made on Ukraine’s terms, it could weaken Putin and Lukashenka with him; that could be our moment to push for change,” said Tsikhanouskaya.

Beyond grand policy measures, allies also have a role to play in supporting grassroots efforts at democratic mobilization. One particularly important fight is in the media space, where most journalists work in exile or at home, although they face arrest and isolation. Yet independent Belarusian media have often proved tech-savvy and continue to operate and overcome barriers to internet access within the country.

Tsikhanouskaya also believes in the importance of preserving Belarusian culture, in stark contrast to the Russian identity that threatens to take over. In strengthening relations with Putin, Lukashenka appears willing to diminish the Belarusian identity to curry favor from the Kremlin. “You might be detained only for speaking the Belarusian language,” said Tsikhanouskaya.

Maryia Sadouskaya-Komlach argued for financial support to organizations trying to support Belarusian cultural identity, both within the country and beyond, where exiles represent an ethnic minority. A forward-facing Belarusian identity might help garner attention to opposition efforts.

This is especially important as Russia and Belarus try to gain ground in the public opinion sphere, hoping to boost support for pro-Russian parties across the EU. One such tactic is the weaponization of legal migration, welcoming legal migrants who hope to seek asylum in Europe in Belarus, and then pushing them to cross borders illegally into the rest of Europe. The hope is that in doing so, Belarus and Russia can spur anti-immigration sentiment and thereby provoke an anti-democratic backlash in Western and Central Europe.

Most recently, Belarus has seen an increase in flights originating from Benghazi in Libya. According to Sadouskaya-Komlach, Lukashenka might hope to use immigration — stopping the flow of illegal migrants — as a bargaining chip against EU leadership.

At present, as so often with dictatorships, the achievement of popular freedom seems far off. That’s not to say the regime has much legitimacy — its rigged elections generate widespread popular disillusionment. The same Chatham House survey found that nearly 40% fewer Belarusians planned to vote in January’s presidential election, with likely participation falling from 75% in 2020 and just 36% planning to do so in 2026. Pro-democracy voters were 50% less likely to cast a vote, citing the belief that the election’s outcome was predetermined and voting against Lukashenka was pointless.

Lukashenka is very clearly disliked and mistrusted by many Belarusians. Tsikhanouskaya and other opposition leaders are fighting to keep alive the hope that one day, sooner rather than later, they will have an opportunity to express this and throw off the country’s pro-Russian dictatorship.

This August 7, 2025, meeting was chaired by CEPA Vice President Christopher Walker and attended by Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, Katia Glod, and Maryia Sadouskaya-Komlach.

This edited version of the discussion is the work of Amy Graham, who is an Intern with the Editorial team at CEPA.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions expressed on Europe’s Edge are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

Europe’s Edge

CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America.