“I used to try to plan my life a long time ahead, but then I realised that all these unexpected bends and new flows are coming all the time into life. It’s something like the weather in Iceland. And I’ve just adjusted to that. When I get an interesting invitation, well, then I’m interested,” says Rúrí, modestly smiling. She’s one of Iceland’s most internationally prolific artists, a pioneer in many ways. Though in recent years she’s mostly participated in group exhibitions in Iceland while having large solo shows abroad, today we meet as she prepares for Tíma Mát, a solo exhibition at the newly established feminist gallery Sind.

The invitation to do this show came from Snærós Sindradóttir, a former journalist and broadcasting host who, while finishing her Art Management degree in Budapest, had a “lightning bolt” moment — she wanted to start a feminist gallery. To my question whether she thinks that such a space is lacking in Reykjavík, she says, “I realised that coming from this paradise of equality in Iceland, we don’t really cherish something like this. We don’t really have a dedicated space which is very proud feminist. We assume that everyone is a feminist, and, therefore, we don’t label things like that. But I truly believe in clarity. I believe that it’s really important to give things the proper name and not have them lie somewhere in between.”

She clarifies that Sind being a feminist gallery doesn’t mean it’s only about exhibiting women and queer artists, “nor even feminist topical works, or political topical works. It’s also about how the operation is — it’s matriarchal.”

Photo by Art Bicnick.

When considering who should open the gallery, Snærós knew exactly who she wanted: Rúrí is her favourite artist. “Rúrí was at the top of the list, and I decided, why pick a big space on a very public street with very good visibility and not try to call my top spot?,” says Snærós.

Soon to be gone

In Tíma Mát, Rúrí’s combining new and old work — the oldest dating back to 2003, and the newest being just this year — bringing together both poetic and topical works. One thing that distinguishes them all, she says, is the fact that “they are nature-inspired.”

“I’ve been working with nature for a very long time,” says Rúrí. “My first work where I’m really working in a conceptual way with nature is from 1978. It’s not in this exhibition, but that’s how far back my interest in nature — and how we as human beings are related to nature — goes.”

“I’ve been studying what effect it could have on the shorelines of countries and continents if all ice on Earth melts due to global climate change.”

Rúrí’s work Archive — Endangered Waters, which represented Iceland in the 2003 Venice Biennale, consists of 52 photographs of waterfalls, many of which have been damaged or no longer exist due to the infamous Kárahnjúkar dam project. Urriðafoss, the lowest waterfall on the river Þjórsá, is the newest addition to the collection of waterfalls that will soon be completely gone. Through her powerful, conceptual observations, Rúrí brings attention to these manmade disasters.

Her concerns about nature extend far beyond Iceland’s threatened waterfalls. As we speak, the exhibition is still being set up, but on the wall behind Rúrí hang 12 cartographic drawings that seem distinctly familiar. I saw the larger-scale works from this series, titled Future Cartography, on view at Hafnarhús just a few weeks ago. “I’ve been studying what effect it could have on the shorelines of countries and continents if all ice on Earth melts due to global climate change,” Rúrí explains. “On the maps, one can see the present shoreline and the possible future.”

The precision of her approach is striking; it’s “science-based,” as Snærós puts it. Rúrí uses the same tools and databases as professional geographers when making these maps. “They are exact. It’s not a fantasy. Every line is correctly drawn according to NASA,” Rúrí says.

Medium matters

As we speak, Rúrí reflects on how much art made in Iceland has been minimalist. “I think it is so important that artists work with contemporary situations,” she says. “For several decades, Icelanders were really focusing on minimal art, and I often wondered whether that was a kind of an escape from being classified as political, because during the Cold War, it could be risky to voice one’s opinions in Iceland, just like everywhere else.”

“I’ve never been a minimalist,” Rúrí stresses, when we speak about her learning to use cartography tools. “I’m using so many different techniques in my art because I always look for the best technique or method to translate the concept into artworks. My life has been studying new techniques constantly,” she says, adding, “The concept is the heart of the artwork. My responsibility is to find the best way to translate the concept into the visual and material.”

“Photographing nature is not like taking a selfie.”

This often involves hours, months, or even years of hard work. “Photographing nature is not like taking a selfie, except for those who go to Reynisfjara,” says Rúrí, when I ask her about two beautiful but moody photographs of the sky and water. “It is often life-threatening. Many of the photographs I’ve been taking, I’ve been on the edge of a cliff to get the [shot of the] waterfall on the other side, just lying on my stomach with my arms outside or on the edge. It’s not an easy job to photograph waterfalls and rivers, and it’s the same with the ocean waves.”

Photographer Art Bicnick, who just returned from Reynisfjara, covering the aftermath of a child’s death on the extremely dangerous beach, interjects, trying to lighten the mood, “Did you take these at Reynisfjara?”

“I’m not stupid. I wouldn’t do that,” says Rúrí. “I take calculated risks. And the thing is, I’m always alone when I’m photographing in nature, so if I make a wrong step, it will be the last. Actually, I’m not seeking the thrill of danger. Not at all. I’m just ready to do everything in my power to do the work well.” She pauses for a moment and then adds, “For instance, going to the former Yugoslavia in the end of the war, it was very challenging. And it was the only time I think I’ve been facing automatic rifles pointing at me more than one at a time. I was in the wrong place, not intentionally.”

Intimate reflections

One of the more personal works in the exhibition, and according to Snærós, in Rúrí’s career, is a selection of works she did in collaboration with the Academy of Senses, a project that aims to introduce contemporary art in unexpected places. “We have been organising exhibitions in the countryside since 2017, going to places where there are no gallery spaces or classical exhibition locations, and putting up exhibitions with contemporary artists, most of whom have relations in the district where the exhibition is held,” Rúrí explains.

Her family on her father’s side hails from the Westfjords, so her contribution to one of these exhibitions is deeply rooted in her childhood memories. “As a child, I spent every summer in the Westfjords where my grandfather was born, and there, nature was our playground — rivers, waterfalls, the ocean, mountains. It was very precious for me, or is precious for me, to have had the opportunity to grow up in nature,” Rúrí explains. “When I was living in Flatey later, for two years after I was a grown woman, I kind of refreshed the experience of nature.”

Photo by Art Bicnick

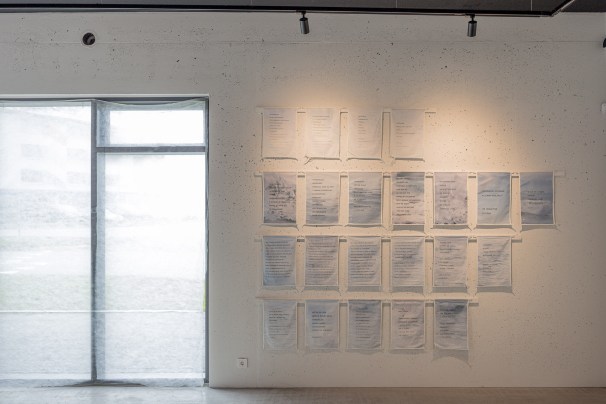

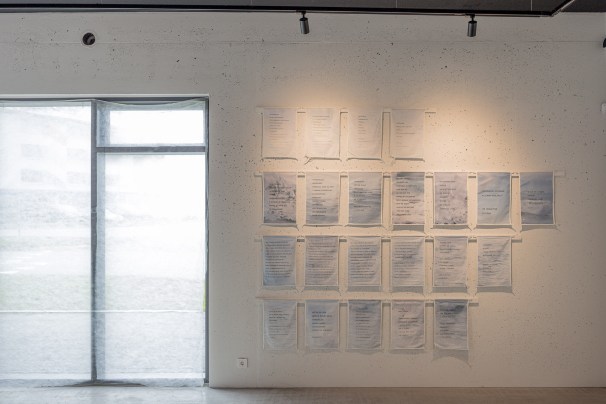

Rúrí gestures toward the wall where the flag works hang — fabric pieces featuring printed ocean photographs with poems written on them. These flags were displayed outdoors in nature, where the harsh weather wore them down, fading the colours. “The idea is similar to what is traditional in Nepal and Tibet,” Rúrí explains, “To put out flags with wishes and when nature has kind of dissolved the flags, nature has accepted the wishes.”

“These are kind of my way of expressing gratitude to the land and nature, the winds and the frost that have given me so much experience, and also referring to my heritage, through the older people in the family, the stories they told — bringing the knowledge from the older to younger generations.”

Before we end our conversation, Rúrí says that the exhibition is about respect for nature in different ways. She explains, “Emotional respect and intellectual respect. From my point of view, we have to consider the consequences of our doings. It’s about these two elements.”

A hard-working artist of remarkable scale and power, Rúrí, whose career spans five decades, shows no signs of slowing down. While preparing to open at Sind, she’s simultaneously working on solo exhibitions in Vilnius and São Paulo that open in just four weeks.

“There was a theory that what makes a difference between humans and animals was the ability to make tools,” Rúrí concludes. “I think that’s a mistake — it’s the ability to make art.”

Rúrí’s exhibition Tíma Mát runs at Sind until September 27.