China’s economy may be slowing again. While the country has weathered the storm of Donald Trump’s trade war better than the United States — thanks to a more diversified set of trade relationships — its domestic economy is beginning to sputter. Exports rose in the last quarter, even as American exports fell, but internal economic growth is less promising.

Industrial output grew 5.7% last month, which is robust by Western standards but still marks a significant reduction from June’s 6.8% rate. More worrying yet is that retail sales grew only 3.7%, sharply down from the previous month’s 4.8% pace.

This is particularly worrying because that 4.8% figure was already low. The basic problem with China’s economy is no secret: domestic consumption is inadequate for a country at its level of development. At barely half of total output, it falls well below the roughly 90% average seen in most developed economies, and this gap has widened as consumption has weakened following the collapse of the housing market. Since property investment is the main saving vehicle for most Chinese households, they have compensated for their losses by tightening their purse strings and boosting their savings.

Faced with inadequate demand, therefore, firms have taken to increasing their exports. That has swamped the world with inexpensive goods and drawn increasing ire from trading partners. If it hasn’t already done so, this export-oriented growth strategy is now finally approaching its limits.

The solution to China’s slowdown is, then, no mystery: reduce investment and increase consumption. Beijing has been trying to bring about a long-overdue rebalancing of the economy, and has enjoyed some recent success in the country’s major cities. There, housing has bottomed out, investment’s share of local output has decreased, and governments have steered what investment does take place towards high-quality, strategic industries.

Unfortunately, governments in smaller cities haven’t yet got the hang of this new approach. Faced with declining growth, they have tried to meet the national target of over 5% annual expansion by investing yet more. The result is excess capacity and output, unprofitable firms, and falling prices — all of which only compounds the downward spiral of Chinese firms.

To successfully rebalance the economy, the country would first need to reduce its excess capacity by allowing a lot of producers to go to the wall. One estimate is that as many as 80% of China’s existing property developers will have to go bust before the market completes its stabilisation. If not quite as dramatic a fall, the same will be true of other sectors, such as car manufacturing.

Then, those firms which survive any shakeout will need to spend more on compensation — whether on higher wages or more generous benefits — in order to facilitate the rise in consumption. That, however, would hit corporate margins, fundamentally challenging the existing model. Powerful interests on which the ruling party’s power rests will feel undermined — hence the struggle to reform.

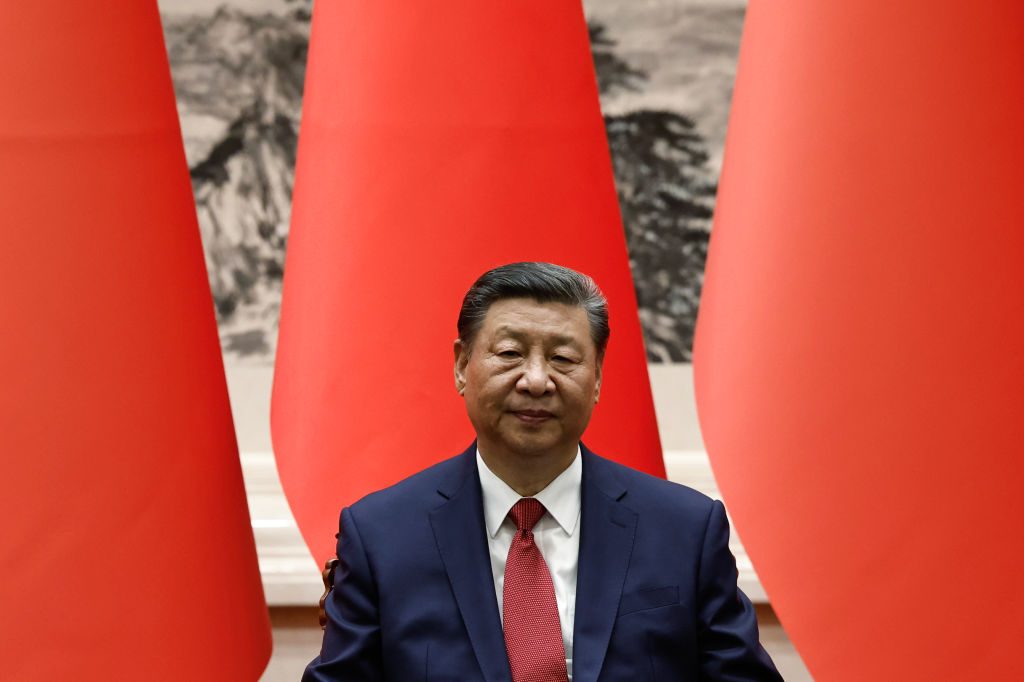

China’s economic travails show that even autocracies struggle to make painful adjustments. But a curious outcome is that we now seem to live in a world where the US and Chinese economies are in various ways converging. The second Trump administration, which is using its political leverage to steer companies towards national goals and penalise those which resist, is starting to resemble Xi Jinping’s model of state guidance of a market economy. But the more worrying convergence is that both economies now appear to be slowing. The result is weakening demand for the rest of the world’s output.

In a world economy that is still struggling to recover from the pandemic recession, that will be a major concern to almost everyone.