We’re a few days into the Novena to St. Augustine for his feast on August 28. To my mind, any excuse will suffice to talk about the thought of that great saint. His feast day in the first year of Augustinian Leo XIV’s pontificate simply can’t be passed up.

During a pause in the conversations on faith and reason at this summer’s 2025 Free Society Seminar in Slovakia, our editor-in-chief and I shared the mutual sense that, after a fair amount of philosophical engagement over the years, maybe the greatest pleasure and light come from reading St. Augustine and one of his influences, Plato.

Augustine thought the Platonists were, of the pagan philosophers, the closest to the greater truths of Christianity. As I read Augustine’s City of God, it seems apparent that he was also familiar with Aristotle. The influences were indirect: he knew Plato through “Neo-Platonic” writers who came centuries after Plato himself, and he had Cicero’s work on Greek philosophy.

Pope Benedict XVI sought to bring elements of Augustine’s theology back to prominence, emphasizing the relational aspects of our being human as equal in importance to our reason. The rational nature that we are given in the image of God had received great attention in the Thomistic tradition, but other aspects of the divinity for which we are built sometimes became obscured.

In his Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas quotes Augustine constantly, more than any other Church Father and (depending on whose word count you trust) more than Aristotle. We can leave the exact accounting to others, but Thomas’s reliance on these two sources is evident.

He seems to have at least two projects in mind. First, to correct the many misinterpretations of Augustine that had sprung up in the eight or nine centuries between the two.

Second, to reconcile the thought of Augustine and Aristotle. Both figures had much to say about the natural life of man and the divine or supernatural aspects of the cosmos.

That reconciliation does not align the two perfectly, and sometimes Aquinas seems to overreach a bit in pressing his case. But it demonstrates that Aristotle’s reason (and ours) can take us a long way towards the truths that ultimately Catholic teaching, based in no small part on St. Augustine’s gifts of faith and reason, can best grasp and express.

As Augustine explains in On Free Choice of the Will, we use our reason to understand better the revealed precepts of the faith, though the Christian mysteries ultimately are beyond us.

Aristotle was not the only pagan philosopher to draw Augustine’s attention. In City of God, he deals with the Stoics.

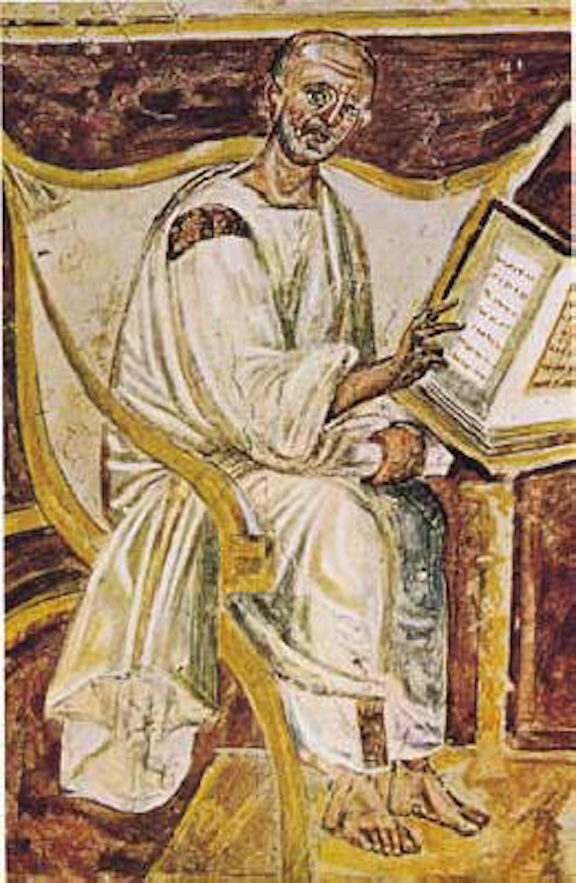

St. Augustine by an unknown artist, 6th century [Lateran Palace, Rome]. This is the earliest known painting (a fresco) of Augustine of Hippo.

St. Augustine by an unknown artist, 6th century [Lateran Palace, Rome]. This is the earliest known painting (a fresco) of Augustine of Hippo.

While some people think of Stoicism as a “cult of suffering,” that’s far from true, if you think of “cult” as worship or love of suffering for its own sake. The Stoics were concerned with peace of mind, which called for accepting suffering as part our “fate” and part of the way we build necessary virtues. We accept suffering, but we don’t love it just to suffer, and that acceptance contributes to peace of mind.

The gods of the Stoics were made of matter, like us. They believed that the suffering we endure is sent or permitted by the gods for our own sake; our mistake comes in thinking it’s an evil, and that shakes our peace.

What Stoicism lacked was an eternal and spiritual meaning to our suffering in this life. With no afterlife, suffering might help us be more virtuous in this life, but it could not lead to spiritual salvation and resurrection of the body.

St. Augustine particularly criticized the Stoics for their approval and even admiration of suicide. Catholic Christianity offered a better way to a true and final peace of mind.

In our day, Stoic resignation appeals to many who, lacking faith, have no hope of the great gifts of Christian surrender. Reading St. Augustine, especially his Confessions and seeing his guilt for his sins transformed into faith, hope and love, might help them open themselves to those gifts.

Again in City of God, Augustine quotes the Psalms to introduce the idea of his title. That city consists of the saints in Heaven and those whose earthly pilgrimage is still underway. These are the souls who have turned to God, worshipping and adoring Him.

By contrast, the earthly city, sometimes called the city of man, consists of those who love themselves and orient their lives and choices accordingly, unconcerned with the divine.

The two cities on earth are intermixed. Earthly political communities – cities – host a mingling of the City of God and the earthly city.

So in this life, there is no barrier between the two cities, though there is a gulf between the City of God’s components in eternity and in time. And if there were such a barrier, no political force, not even a Roman emperor, could breach it. Only God incarnate could, as He crossed the gulf to us.

Both cities have peace as their aim, as the Stoics too hoped for. The City of God has in Heaven – and is moving towards on earth – a final peace. The city of man also wants peace, if only to enjoy the temporal goods it prefers to the prospect of the divine.

We are fortunate, says Augustine, if we live in a time and place where we can enjoy earthly peace.

But all of our attempts at progress will never make the earthly city into the City of God on earth. That making of all things new will only be complete at the end of time, through God’s choice, not our will. And while our efforts to improve our condition and reduce suffering for those around us are essential, our demand for earthly perfection is futile and even dangerous.

Pope Benedict presented us with a great gift in reminding us of St. Augustine’s teaching. Now we’ll see what the new pope of the great saint’s order will give us on his feast day.