Since the start of the war in Ukraine, Western media as well as public forums on social media have seen countless debates, opinions, and analyses of the potential threat that Russia would pose to Europe as a whole. This debate motivated, in no small part, the Swedish and Finnish entries into NATO.

Generally speaking, there are two main arguments being made regarding Russia and Europe:

1. The Russian military is weak, as is the country’s economy. The West must remain steadfast in its commitment to Ukraine, because it is only a matter of time before the Russian economy implodes and they will be defeated.

2. The Russian military is vast, strong, and formidable. It poses a grave threat to the European continent; before we know it, their tanks will roll into Paris.

Judging from how the arguments often go in defense of Europe’s growing defense budgets, one easily gets the impression that political leaders both in Brussels and in Europe’s national capitals believe both these arguments to be true. Unfortunately, that is not possible: the second argument necessitates a strong, resilient Russian economy—the very opposite of what the first argument suggests.

The two arguments above cannot be true at the same point in time. Either Russia’s economic implosion is imminent, or its economy is resilient enough to at least continue the war in Ukraine.

I understand those who predict the collapse of the Russian economy; it is partly a rational argument based on how the economic sanctions against Russia were sold to us. Partly, it is a kind of wishful thinking wrapped in the dispassionate attire of a forecast. The underlying argument is that Russia started this war by invading Ukraine; therefore Russia is the perpetrator and should be duly punished. An imploding economy would be a punishment fitting the crime.

With that said, the more I search the media, the research literature, even academic publications, the more I am struck by the lack of close-examination writing on the Russian economy. It stands to reason that those who believe in a Russian economic collapse should be monitoring their economy with great care; if a country with 164 million people really were to implode economically, it would cause a humanitarian crisis of epic proportions.

Given that Russia is in possession of what is probably the world’s largest arsenal of nuclear weapons, an implosion of that sort should be the cause of preparations for an urgent global intervention to keep those nukes from ending up in the wrong hands.

Yet I see no indications of any such preparations. I see no independent studies that explain how the West would prepare to intervene when the Russian economy implodes. I cannot find any research on the timing of that event. The closest I can get is the study from Yale University three years ago, which I criticized heavily for its analytical inconsistencies, its methodological flaws, and its distortion of facts.

Leaving the demagoguery from pro- and anti-Russian agitators aside, we can take a look at the Russian economy through established global producers of economic statistics. One reliable source is the United Nations national accounts database; another, and very different in nature, is TradingEconomics.com. The former is a multinational bureaucracy with significant resources on hand; the latter is a private company that delivers economic statistics based on subscriptions or single purchases.

Both the UN national accounts office and TradingEconomics have been around long enough to have proven the quality of their products. This also means that they have established methods for compensating for inconsistencies and methodological differences in the national collection of original data.

This is important when it comes to examining the Russian economy. It is easy to find critics who—often without any formal training in economics—dismiss Russian economic statistics as a priori unreliable. By relying on established statistical outlets, we neutralize such criticism and can therefore ignore it from hereon.

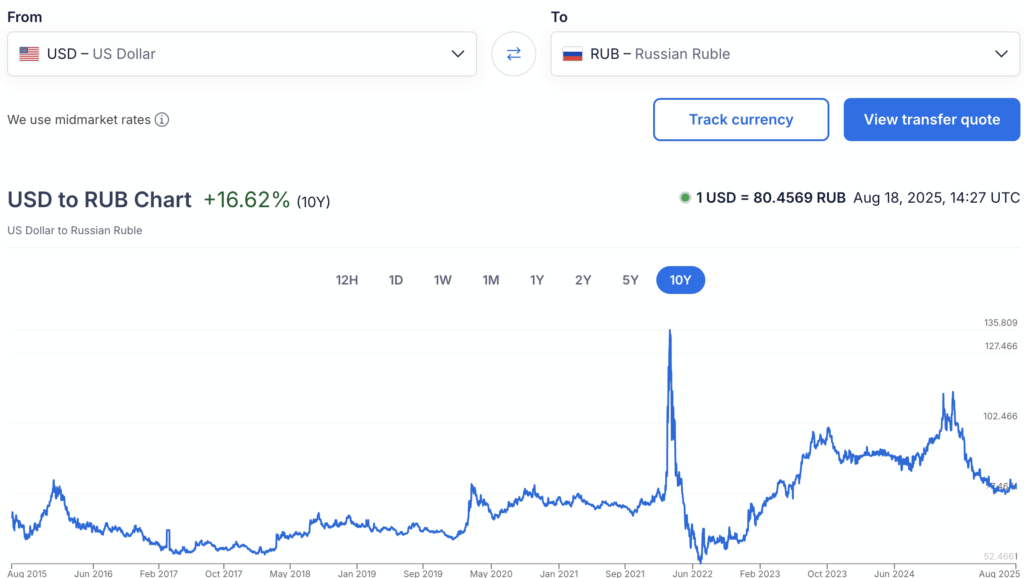

A nation’s exchange rate is a good first-impression indicator of how its economy is performing. Figure 1, courtesy of xe.com, reports the rate between the U.S. dollar and the Russian ruble over the past 10 years. The rate was relatively stable in the years leading up to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. A short but intense period of exchange rate turbulence replaced the previous calm; notably, though, that period resulted in a short-term strengthening of the ruble. After a weakening of the Russian currency, it has gained new strength this year:

Figure 1

Source: xe.com

Source: xe.com

The strengthening of the ruble in the past several months indicates that the Russian economy is not at all weak. It does not mean that the Russian economy is an unbreakable machine of prosperity and growth—far from it—but it suggests that when it comes to international transactions, for the purposes of both trade and financial investments, Russia appears to be doing comparatively well.

To make sure the ruble resiliency in Figure 1 is not the result of a weakening of the dollar, Figure 2 presents the same exchange-rate comparison but with the euro instead of the dollar. The long-term pattern as well as the recent ruble appreciation are largely the same as for the dollar:

Figure 2

Source: xe.com

Source: xe.com

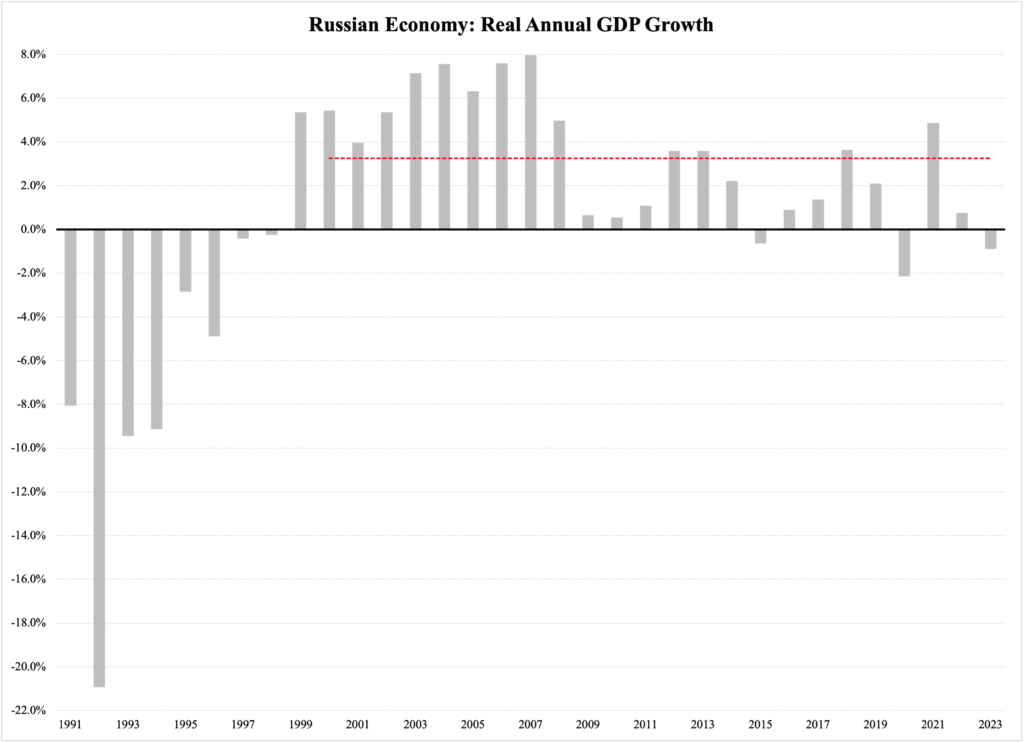

Turning to more substantive statistics, Figure 3 reports annual GDP growth figures—adjusted for inflation—from 1991 through 2023. Anyone looking for an economic implosion in Russia should examine closely what happened in the 1990s: from the dissolution of the Soviet Union to the turn of the millennium, 39% of their economy vanished.

Since the turn of the millennium, the Russian economy has grown at rates that are impressive by European standards. The dashed red line in Figure 3 reports the 3.2% average inflation-adjusted GDP growth rate since the year 2000. Although real growth rates have been lower more recently, the ups and downs are consistent with a regular economy going through growth periods and recessions.

Figure 3

Source of raw data: United Nations

Source of raw data: United Nations

Since the UN database only provides data through 2023—the 2024 figures will not be out for a while—we can of course not use Figure 3 to determine the state of the Russian economy today. However, the long-term average growth and the cyclical pattern tell us that Russia has a perfectly normal, industrialized economy that by and large functions like other industrialized economies.

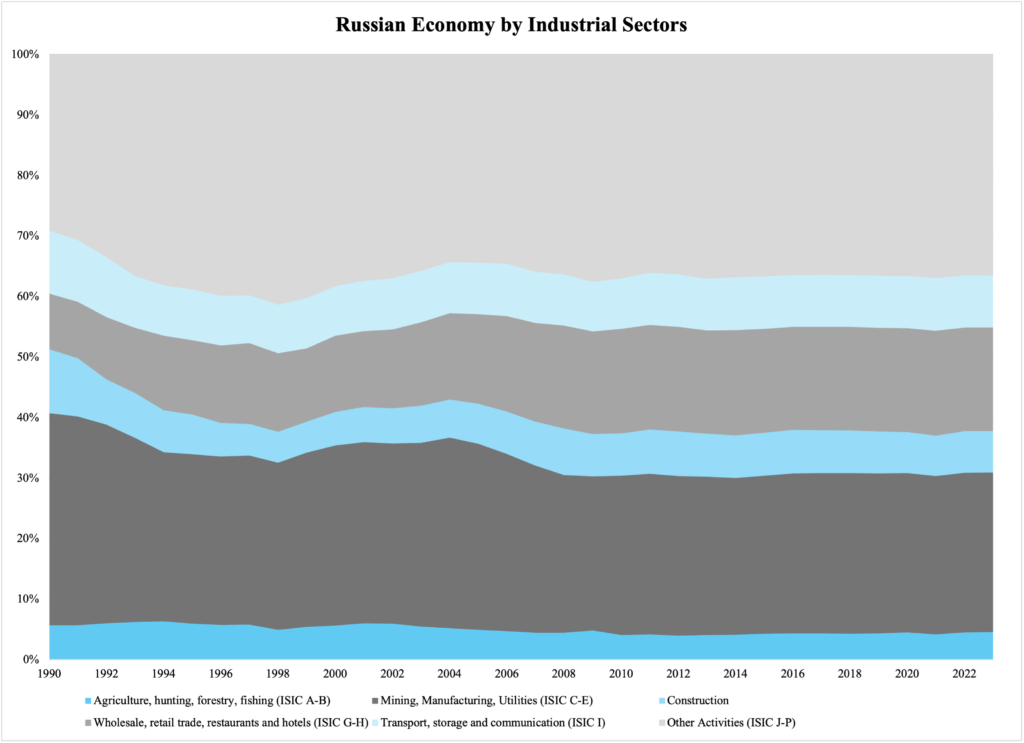

Figure 4 confirms the same point by reporting Russia’s GDP broken down by industrial sector. The largest one, “other activities,” consists of all kinds of services, from banking and finance to engineering services and tourism.

Figure 4

Source of raw data: United Nations

Source of raw data: United Nations

Manufacturing, which is part of the broader group that also includes mining and utilities, contributes 15% of the value to Russia’s GDP.

From a long-term structural perspective, the Russian economy looks solid. A closer look at the present paints a somewhat less positive picture. According to TradingEconomics.com,

Real GDP growth in 2024 was 4.1%, but the latest year-to-year number for the second quarter of 2025 is only 1.1%;

Unemployment is a low 2.2%, but it is unclear how large a part of that is attributable to military enlistment and to the state-funded war industry;

Inflation is on its way down, with the latest observed rate being 8.8%, although the decline is too slow for a brisk return to price stability;

The Russian central bank currently holds its deposit rate at 18.7%, which is extreme compared to Western economies;

The consolidated government debt is only 16.4% of GDP, but the budget deficit is at 1.7% of GDP, and it shows no signs of ending.

In combination, the high inflation rate, the extreme interest rate, and the budget deficit are a growing threat to the Russian economy. It is difficult to say exactly how serious that threat is, but if the Russian war effort continues at its current levels, there is a good chance that the deficit becomes an acute problem a year from now.

Add to this the fact that gross fixed capital formation, or business investments, appear to have declined sharply in the last year. The gut reaction among Western economists is to attribute this to very high interest rates, but based on my own research, I beg to differ, at least to some degree. In my studies of the relationship between interest rates and capital formation, I have never found a higher correlation than about 10%.

With that said, I have not looked particularly at economies with extremely high interest rates, a category to which the Russian economy no doubt belongs. The correlation could be higher, which is bad news, of course, for Russia. However, it is also good news, as the central banks can execute a series of stimulating rate cuts once the war effort is over and inflation under control.

To sum up, Russia’s economy remains in good shape and is able to provide for the war effort. However, things will change for the worse in the relatively near future, possibly already as soon as this winter.