Gone are the days of preference for sons. South Korea is arguably now the world’s No. 1 daughter-loving nation

Illustration by Nam Kyung-don

Illustration by Nam Kyung-don “It’s a boy. I need words of consolation.”

An expectant mother on Korea’s largest online parenting forum, Moms Holic, expresses her frustration after learning about the gender of her baby-to-be.

Others share that sentiment.

“My husband and I plan to have a second child in two to three years, so we were really hoping the first would be a girl. Honestly, the prospect that we might have two boys in a row feels overwhelming,” another expecting mom writes, after an ultrasound session showed her first child would be a boy. “I feel sorry for the baby, but I can’t help feeling disappointed.”

Such sentiments, once unthinkable in a society that favored sons as heirs and family heads for centuries, have become common among expecting moms and dads, and even those already with children. Notoriously, in the patriarchal Korea of the past, families without sons were seen as doomed to end their lineage, with wives failing to bear sons taking the most blame.

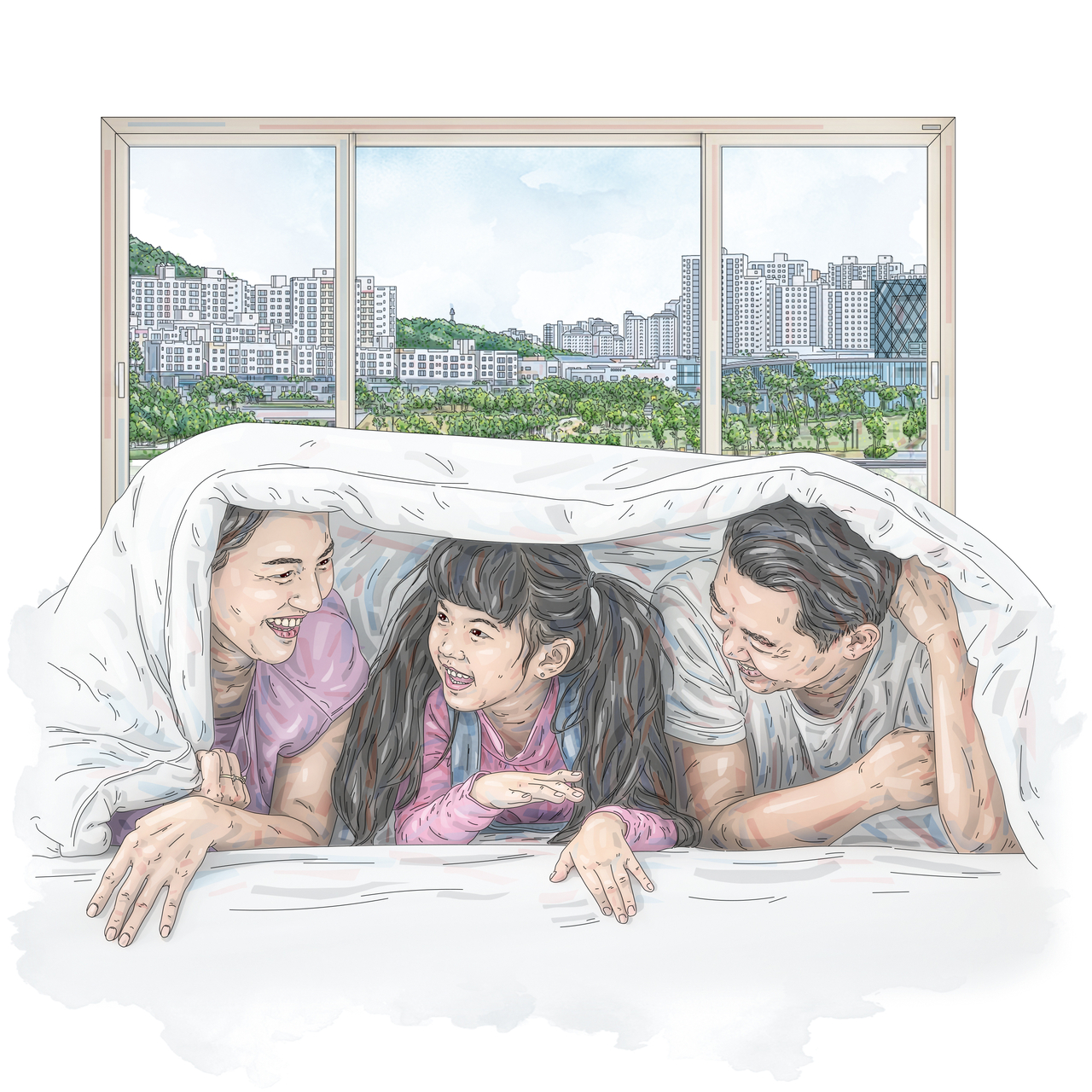

In a post uploaded on Aug. 14 to an online mom community, the writer says she has been crying for four days since learning her baby will be a boy. (Naver)

In a post uploaded on Aug. 14 to an online mom community, the writer says she has been crying for four days since learning her baby will be a boy. (Naver) Some would go so far as to post ultrasound images showing their baby’s genital area, hoping for a second opinion or a glimmer of hope.

“I’m 15 weeks pregnant, and the ultrasound shows something between the baby’s legs that looks like a penis,” one post reads. “I’ve heard the umbilical cord can sometimes get in the way and look like this. The doctor said it seems to be a boy, but could it still turn out to be a girl later?”

The desire for a daughter has sparked myths and online advice claiming to know ways to avoid conceiving a boy or to increase the chances of having a girl, although, of course, none of these are supported by science. In the past, such eagerness for tips would have been for conceiving a boy.

‘World’s No.1 daughter-loving nation’

South Korea is now the world’s No. 1 daughter-loving nation, a survey shows.

A Gallup International survey of 44,783 adults in 44 countries, conducted between October last year and February this year, asked, “If you could have only one child, would you want a son, a daughter, or does the gender not matter?”

Twenty-eight percent of 1,534 Korean respondents answered that they would prefer a daughter. Barely half of that, at 15 percent, would prefer a boy, while 56 percent said gender is irrelevant. This placed Korea at the top in terms of daughter preference, ahead of Japan, Spain and the Philippines, which all tied at 26 percent.

Gender preference in Korea has completely reversed in just three decades. In the same survey in 1992, 58 percent of Koreans said they preferred a son, while only 10 percent wanted a daughter.

A mother and daughter lie on a bed, hugging and smiling. (123rf)

A mother and daughter lie on a bed, hugging and smiling. (123rf) Local polls likewise show an increasing favor for daughters. A Korea Research survey released in June last year found that 62 percent of 1,000 adults nationwide agreed that “every family should have at least one daughter,” while only 36 percent expressed the same about sons.

The shift in gender preference is also evident in birth statistics.

The sex ratio at birth in 1990 was 116.5 boys for every 100 girls, indicating possible prenatal selection by parents favoring boys. By 2023, the figure is down to 105.1, aligning with the natural sex ratio at birth, according to Statistics Korea.

‘Less demanding to raise, more caring’

Why do the parents of today want daughters?

Oh Seo-eun, 42, mother of an 8-year-old son and a 5-year-old daughter, told The Korea Herald that she truly feels the difference between raising a boy and a girl when spending time outdoors. She says girls, in general, tend to be less demanding from a childcare perspective.

“When we go to an amusement park, my son wants to keep riding rides or running around, while my daughter enjoys not only the rides but also browsing toys at the gift shop or sitting in a cafe to have ice cream. So when we go out, my husband usually takes charge of our son,” she said.

Boys often have higher energy levels and, without proper supervision, may be more prone to accidents or getting into trouble, she added.

“When my son was a newborn, his insurance premium was 10,000-20,000 won ($7-$14) higher than a girl’s. Back then I didn’t understand why, but now I do. Boys are definitely more active, and it takes a lot more energy from moms.”

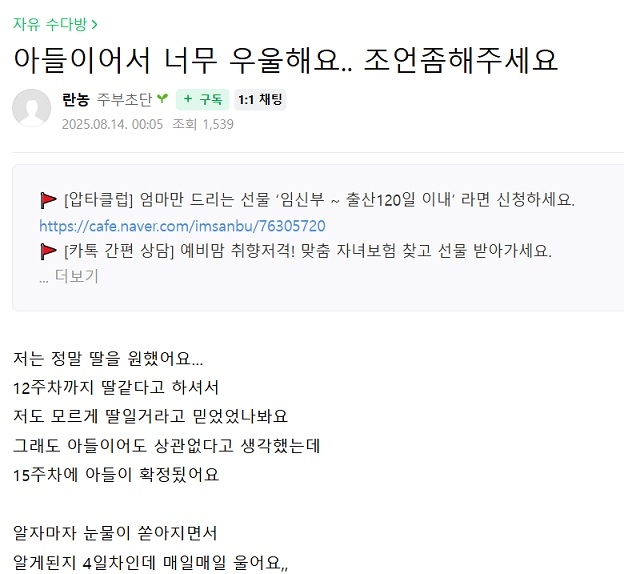

According to a woman surnamed Yang, 37, who is raising a 3-year-old son and a 1-year-old daughter, the gentler nature of daughters brings a different kind of emotional warmth.

“Our son shows affection through physical gestures like hugs and kisses, while our daughter often reads our facial expressions and shows affection with words. Daughters seem more thoughtful and maybe that’s just their nature,” she told The Korea Herald.

Yang’s son (left) and daughter look out the window of their apartment. (Yang)

Yang’s son (left) and daughter look out the window of their apartment. (Yang) Kim Sang-eun, 40, who has an 8-year-old son and a 4-year-old daughter, echoed Yang’s view that girls tend to be more caring, comparing herself with her older brother.

“I call my parents more often than my brother does, and I’m the one who makes sure to prepare gifts for their birthdays and occasions like Parents’ Day. I would never force my daughter to look after me, but I just feel like I’ll be closer to her, and I’m already looking forward to when she grows up,” she said.

Kim’s children observe a street cat. (Kim Sang-eun)

Kim’s children observe a street cat. (Kim Sang-eun) “From clothes and cosmetics to the experiences of pregnancy and childbirth, mothers often find more common ground with daughters, which is why many mothers hope for a daughter,” she said.

Kang Soon-ae, 73, who raised two daughters and a son and is now a grandmother to three girls, says she feels fortunate to have caring daughters.

“After my children started working, my daughters would still call just to chat about little things and check on me, like what I had for lunch. Mothers of only sons often envied that,” she said. She added that when her daughters gave birth to girls, she felt happy, knowing those baby girls would one day grow up to be their mothers’ best friends.

Aging concerns behind daughter preference

The preference for daughters in Korean society also reflects the growing role that daughters play in supporting their parents through various challenges in old age, such as illness and financial difficulties, according to Cho Young-tae, a professor of public health sciences at Seoul National University’s Graduate School of Public Health.

“Traditionally, sons were expected to carry on the family name and care for their parents, but today daughters are seen as the more dependable caregivers, especially when parents fall ill in old age,” he said.

A 2023 survey by Hanyang University’s Graduate School of Clinical Nursing found that 82.4 percent of 125 family members providing home care for elderly relatives with dementia were women, with daughters accounting for 42.4 percent, compared to just 15.2 percent for sons.

Other experts noted that lowered expectations of financial support from children have fueled the preference for daughters.

“In an era where young people struggle economically due to job shortages and soaring housing prices, parents no longer expect their children to support them financially. The focus of family relationships and the meaning of filial piety are shifting from economic to emotional value,” said Koo Jung-woo, a sociology professor at Sungkyunkwan University.

“Since daughters are often considered better at building emotional bonds, many parents feel it is essential to have a daughter when thinking about old age. Ultimately, concerns about later life seem to be reflected in the growing preference for daughters.”

cjh@heraldcorp.com