Over the summer, federal enforcement operations have continued to hit the Central Coast, and verified reports of ICE, Border Patrol, or other federal agencies conducting immigration-related activity are coming through the 805 Immigration Coalition’s 24/7 Rapid Response Hotline nearly every day.

In June, enforcement operations in Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, and Ventura counties manifested through crews of federal agents, often masked, rolling in unmarked vehicles, and donning bulletproof vests carrying a variety of agency insignia — ICE, ERO (Enforcement and Removal Operations), HSI (Homeland Security Investigations), FBI, or the generic “Police” — making arrests without warrants in public areas. According to advocates with 805 UndocuFund, an organization keeping track of enforcement activity on the Central Coast, many of these arrests occurred in areas with high populations of Latino working-class residents, including Santa Barbara’s Eastside and Westside neighborhoods.

Enforcement operations continued through June, stoking community fears and sparking public demonstrations where immigrant rights advocates called on local governments to protect undocumented and mixed-status residents. On July 10, community concerns intensified when federal agencies raided two Central Coast cannabis facilities and arrested more than 300 workers — the largest single-day operation since the Trump administration launched its mass deportation agenda.

Following the July 10 raids, legal observers with the Rapid Response Hotline have noted that federal agencies changed up their tactics, and while there are still reports of immigration-reated arrests a few times a week, there have been fewer daily calls and messages coming into the 24/7 hotline.

Beatriz Basurto, a co-organizer of the Rapid Response Hotline with 805 UndocuFund, says she is hesitant to say federal authorities have eased up on daily operations. “I’m careful about saying they’ve slowed down,” she said. “If anything, they’ve started to do it more quietly. It’s still happening — they’re still kidnapping people — but it’s been more low-profile.”

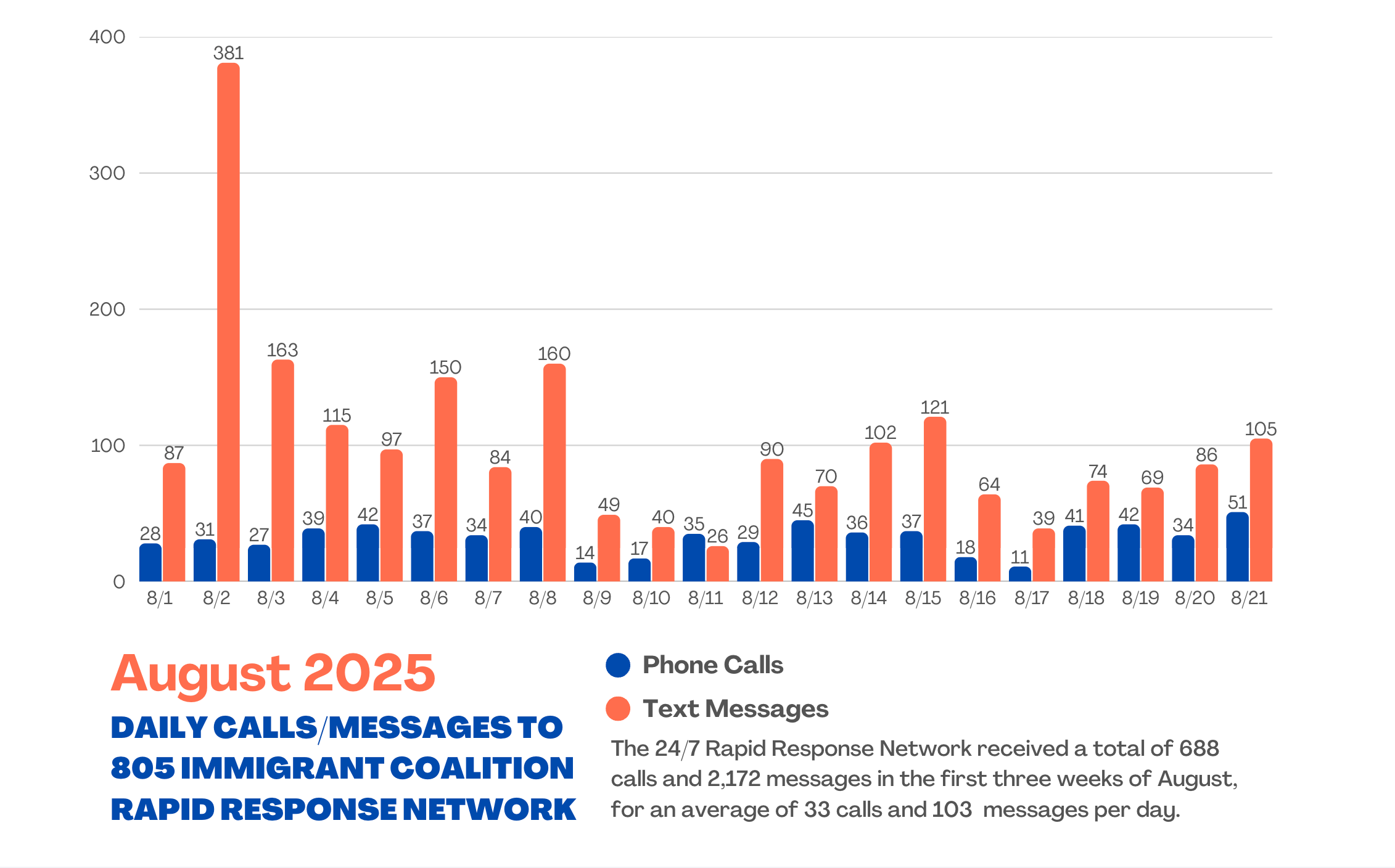

The Rapid Response Hotline fielded 688 calls and 2,172 text messages in the first three weeks of August, averaging about 33 calls and 103 messages a day. Hotline volunteers investigate public tips and send community alerts for verified ICE activity. On August 21, the hotline recorded five ICE arrests, including a report of a U.S. citizen who was temporarily detained by ICE officers who said his car matched the description of a suspect.

[Click to zoom] The Rapid Response Hotline saw a slight slowdown in its daily calls in August, following a boom in immigration enforcement activity in June and July. | Credit: Chart made by Ryan P. Cruz; data provided by 805 UndocuFund.

In recent months, Basurto says, federal authorities have become more aware of advocates and legal observers holding daily community watches, and many immigration arrests now occur in the early mornings or late at night when there’s fewer potential for public witnesses. It also appears as though ICE and other agencies have been making more arrests of undocumented individuals at local jails, courthouses, and the regional ICE offices, she said. These types of arrests can make it difficult for witnesses to keep track of arrest numbers.

“We assume that, because they are not meeting their quota on the streets, they are now getting people from their buildings and offices,” Basurto said. “Observers have witnessed people going in and not coming back out.”

Basurto says the targeting of undocumented and mixed-status families has left people feeling like they “have to look over their shoulders,” and made many question whether they would attend large public gatherings such as Santa Barbara’s Fiesta — though immigration enforcement has, to this point, steered clear of major community events.

Technically, the temporary restraining order brought about by the ACLU’s lawsuit challenging the federal government’s “indiscriminate” immigration enforcement put a stop to the random arrests based on racial profiling in Southern California. But advocates with 805 UndocuFund are not convinced that federal agencies will comply with the order, and there are worries about the potential for even more aggressive enforcement once ICE has access to its $170 billion budget in October.

“That’s looming over us, because that’s when their new budget kicks in,” Basurto said. The government launched an effort to hire up to 10,000 more deportation officers, offering signing bonuses to new recruits and lifting age requirements to attract more applicants. “All these things they’re doing, it’s only setting up for disaster. They are signing up to traumatize these families and communities.”

While ICE is in search of new officers, 805 UndocuFund continues to host community training sessions for volunteer legal observers and to offer support for families who have been impacted by immigration enforcement — including children returning to school after enduring the trauma of losing one or both parents to deportation.

“The best we can do is funnel people’s anger into support for immigrants,” she said. “We have to make sure we are changing the culture of how we look at all of this. We shouldn’t accept this normalization of the kidnapping of our community members.”