Third, external security assistance from the US, besides China, is a crucial multiplier. Pakistan received about $4.07 billion in foreign military financing over 2002-17, and sustained international military education and training. Congressional reporting lists the rehabilitation of F-16s, delivery of advanced medium range air-to-air missiles and Sidewinder missiles, Harpoon anti-ship missiles, P-3C upgrades and sophisticated night-vision and targeting systems—a suite that gave Pakistan credible air-superiority counters, sea-denial tools and surveillance and reconnaissance reach. Even as security assistance contracted after 2016, the US approved a $450-million sustainment package for Pakistan’s F-16 fleet in September 2022.

Moreover, the China-Pakistan axis transcends hardware. Exercise regimes amplify the technical effect of hardware transfers. The ‘Shaheen’ air exercises include dissimilar air-combat training; the ‘Warrior’ drills incorporate three-dimensional manoeuvre and air-ground integration; and the ‘Sea Guardian’ exercises have progressively introduced anti-submarine warfare, air defence, and maritime interception drills.

Fourth, the operational logic behind Pakistan’s claim is not to assert parity in every domain, but to claim theatre-level contestability to impose costs on India in the geographic slices and time horizons. Pakistan’s force design reflects that logic, concentrating on affordable, survivable combat platforms with modern sensors and stand-off weapons.

Fifth, information operations, intelligence expenditure and denial/obfuscation capabilities amplify Pakistan’s political coercion. A non-trivial portion of Pakistan’s security spending, nearly 20 percent, is allocated toward shaping narratives, cyber operations, and influence campaigns that impose strategic political costs on India.

Nevertheless, structural weaknesses impose hard ceilings. Pakistan’s tax-to-GDP ratio is among the world’s lowest, inflation spikes have eroded procurement power, and foreign exchange constraints routinely delay payments. These realities argue against a prolonged conflict in which India’s deeper pockets and larger industrial base would always outnumber Pakistan’s inventories.

For India, the counter-argument emphasises cumulative modernisation. But Indian modernisation faces its own headwinds—procurement lag, jointness frictions, and the need to split attention across two fronts with China.

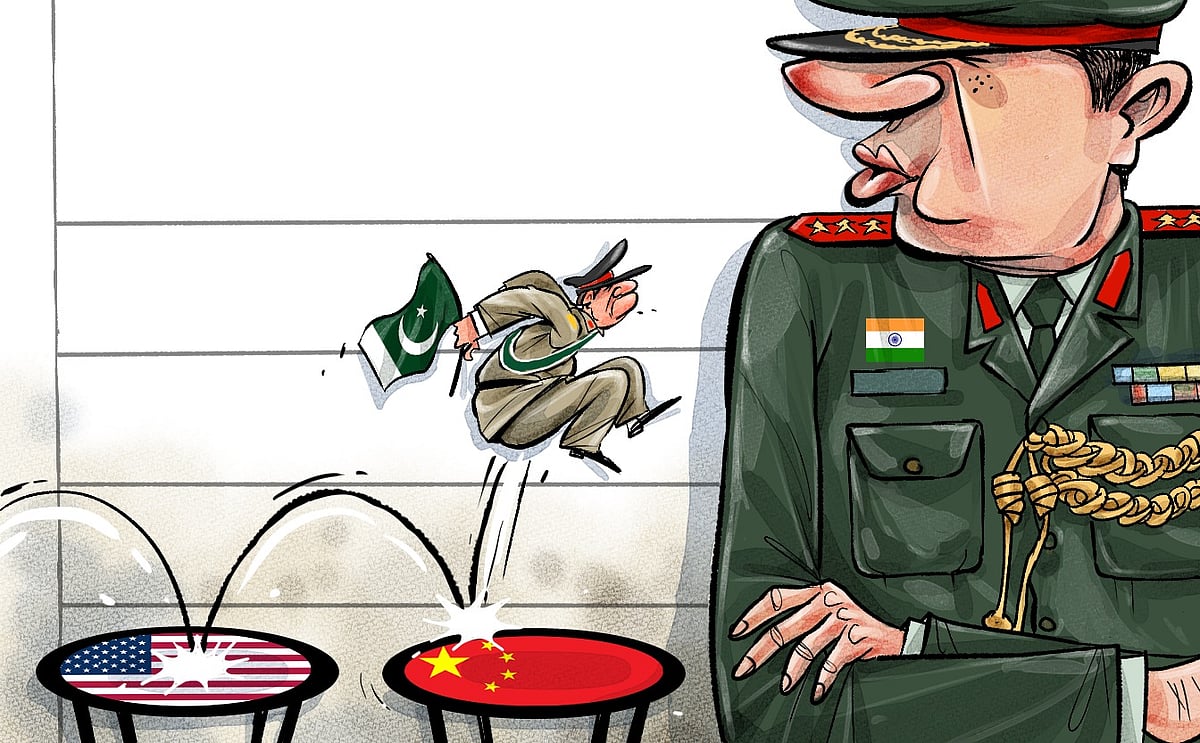

Pakistan exploits precisely those windows where India’s coordination costs are highest. Pakistan does not need to win everywhere; it needs to prevent India from achieving rapid, politically decisive gains anywhere.

Pakistan’s claim to ‘conventional parity’ with India is best interpreted as a claim about theatre-level, time-limited and domain-specific contestability rather than absolute equivalence.

If parity is read as comprehensive equivalence across duration, domain and strategic reach, then the claim fails. India, too, needs to up its game. Either increase defence spending from an average of 2.43 percent of GDP during 1960-2022 to at least 4 percent over the next decade, or significantly reduce the multi-theatre military challenges it confronts.

Manish Tewari | Member of parliament, lawyer, and former Union I&B minister

(Views are personal)

(manishtewari01@gmail.com)