Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth’s indifference to the Constitution and American law, as well as his disdain for “tepid legality” as the governing standard for the use of U.S. military power, places him at sharp odds with those who founded this nation and held the office of the Presidency. John Quincy Adams, after serving as secretary of state and president, said, “the war power is strictly constitutional.” Like his predecessors in the nation’s highest office, Adams fully understood that the president’s authority over foreign relations was no less circumscribed than the domestic powers conferred by the Constitution.

Hegseth’s blithe disregard of law is unbecoming of a constitutional officer whose authority exists only by virtue of that vested in his office by the Constitution, which he has sworn an oath to uphold, and such powers as Congress, to which he is legally accountable and subject to removal through impeachment, may choose to confer upon him. Hegseth’s arrogant dismissal of legal boundaries invites the scale of scorn that the founders reserved for usurpers, those who abused power and obstructed justice, beginning with King George III, whom they singled out in the Declaration of Independence as a tyrant.

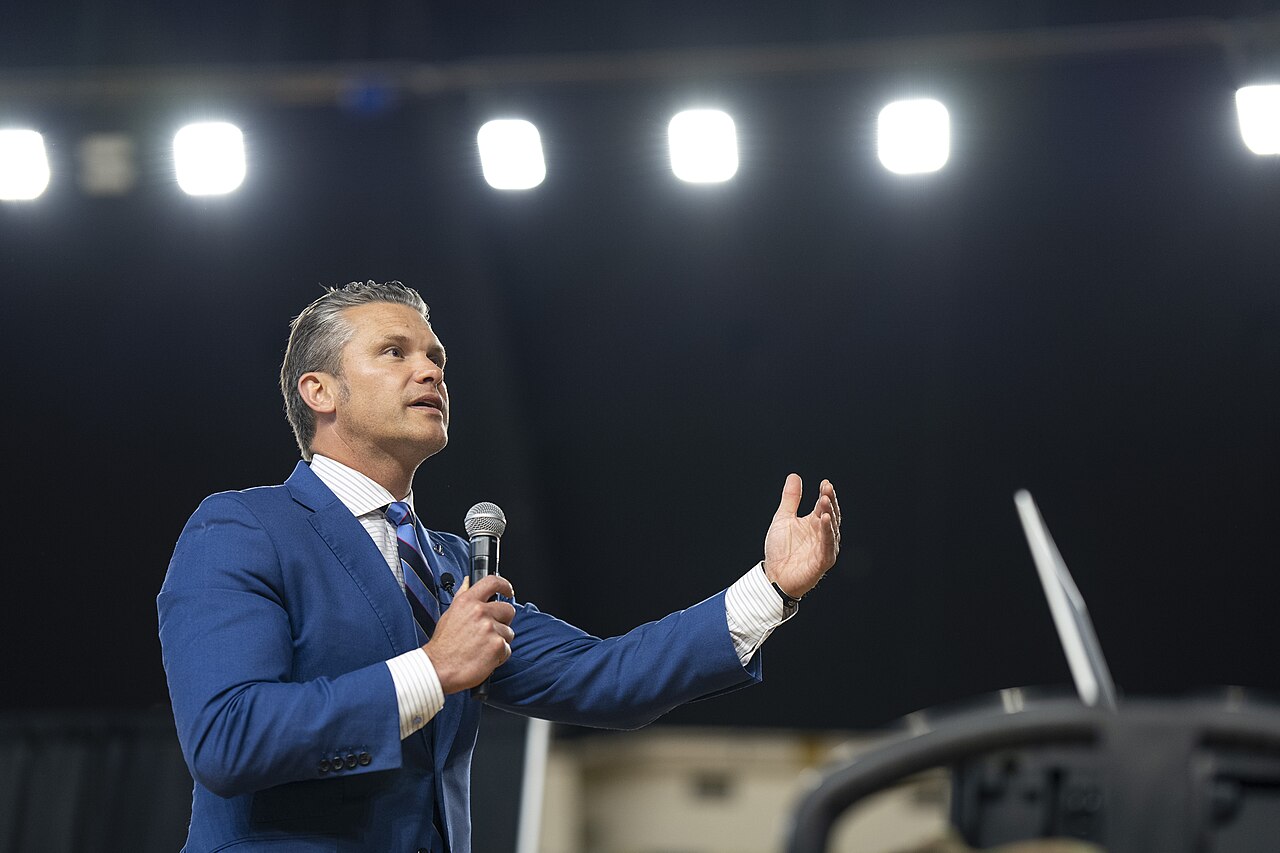

Hegseth’s enthusiasm for President Donald Trump’s executive order changing the name of “Department of Defense” to the “Department of War” was reflected in his slam-poetry-like explanation of the rebranding as not just a name change, but a shift in attitude, posture and strategy. Hegseth said the war department is “going to go on offense, not just defense. Maximum lethality, not tepid legality. Violent effect, not politically correct.” Successful prosecution of wars always has been, and always will be, the goal of our armed forces, but it is critical to recall that war, from its commencement to its conclusion, must be conducted in accord with the Constitution and applicable laws. On this point, the founders, and judicial rulings issued at the dawn of the republic, were crystal clear.

Respect for the Constitution and its allocation of the war power to Congress, fortified by the presidential oath of office and the Article II duty “to take care to faithfully execute the laws,” informed the decisions of founding presidents when questions of war and military hostilities arose. No early president — Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, for example — shared Hegseth’s disdain for legality.

In 1801, and again in 1805, President Jefferson, faced with military threats from Tripoli and Spain, respectively, refused to go on “offense,” when, “considering that Congress alone is constitutionally invested with changing our condition from peace to war, I have thought it my duty to await their authority for using force.” The threat of invasion did not stop Jefferson from consultation with Congress.

President Madison, the chief architect of the Constitution, reiterated the constitutional governance of the use of force on June 1, 1812, when he called attention to the English attacks on American shipping. He referred to Congress the question of whether we should oppose “force to force in defense of our national rights,” which he said, was a “solemn question which the Constitution wisely confides to the legislative department of the Government.”

After the adoption of the Monroe Doctrine, Colombia sought protection from France in 1824. President Monroe, who was a delegate to the Virginia Convention, stated, “The Executive has no right to compromise the nation in any question of war.” He echoed Secretary of State Adams, who declared that the Constitution vests that power in Congress, alone.

Chief Justice John Marshall, a vigorous participant in the Virginia Ratification Convention, stated in Talbot v. Seeman (1801): “The whole power of war being, by the Constitution vested in Congress, the acts of that body can alone be resorted to as our guides in this inquiry.” There was no departure from this understanding in the crisis of the Civil War. In the Prize Cases (1862), the high court held: “By the Constitution, Congress alone has the power to declare a national or foreign war.” The president, “has no power to initiate or declare war against a foreign nation or a domestic State. If a war be made by invasion of a foreign nation, the president is bound to resist force by force. He does not initiate the war but is bound to accept the challenge.”

In matters of war and peace, the founders, unlike Secretary Hegseth, demonstrated respect, not disdain, for legality.