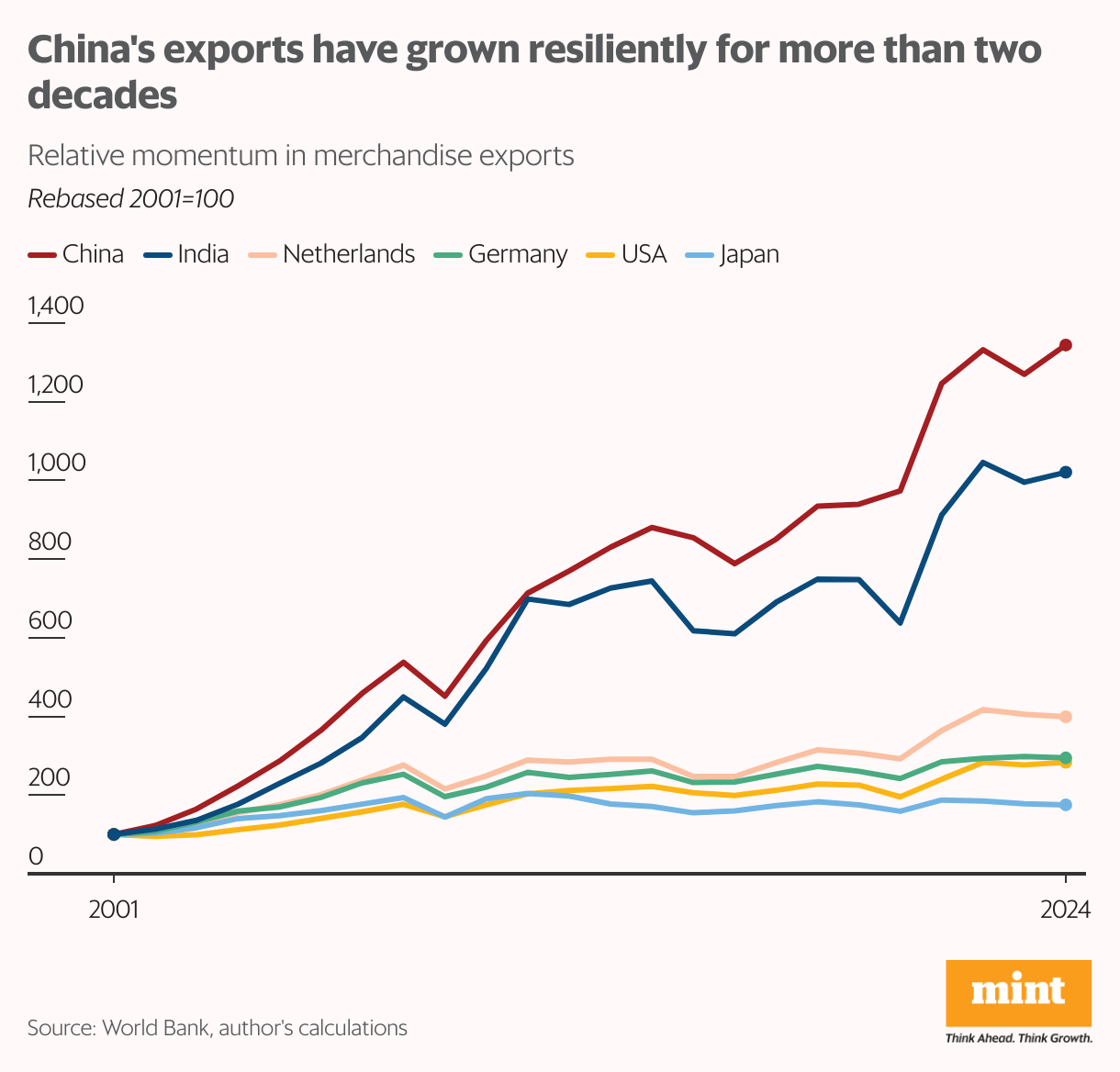

Does this mean that the Chinese export juggernaut has been halted? Well, not really.

In fact, exports from China appear to be remarkably resilient even in the face of trade tensions. China has been preparing for a trade shock since tariffs were first imposed in 2018, during the previous Trump presidency. By the time Trump rolled out his new tariff plan again in 2025, Chinese authorities had already taken steps to mitigate the risk they faced from relying so heavily on exports.

Find new markets

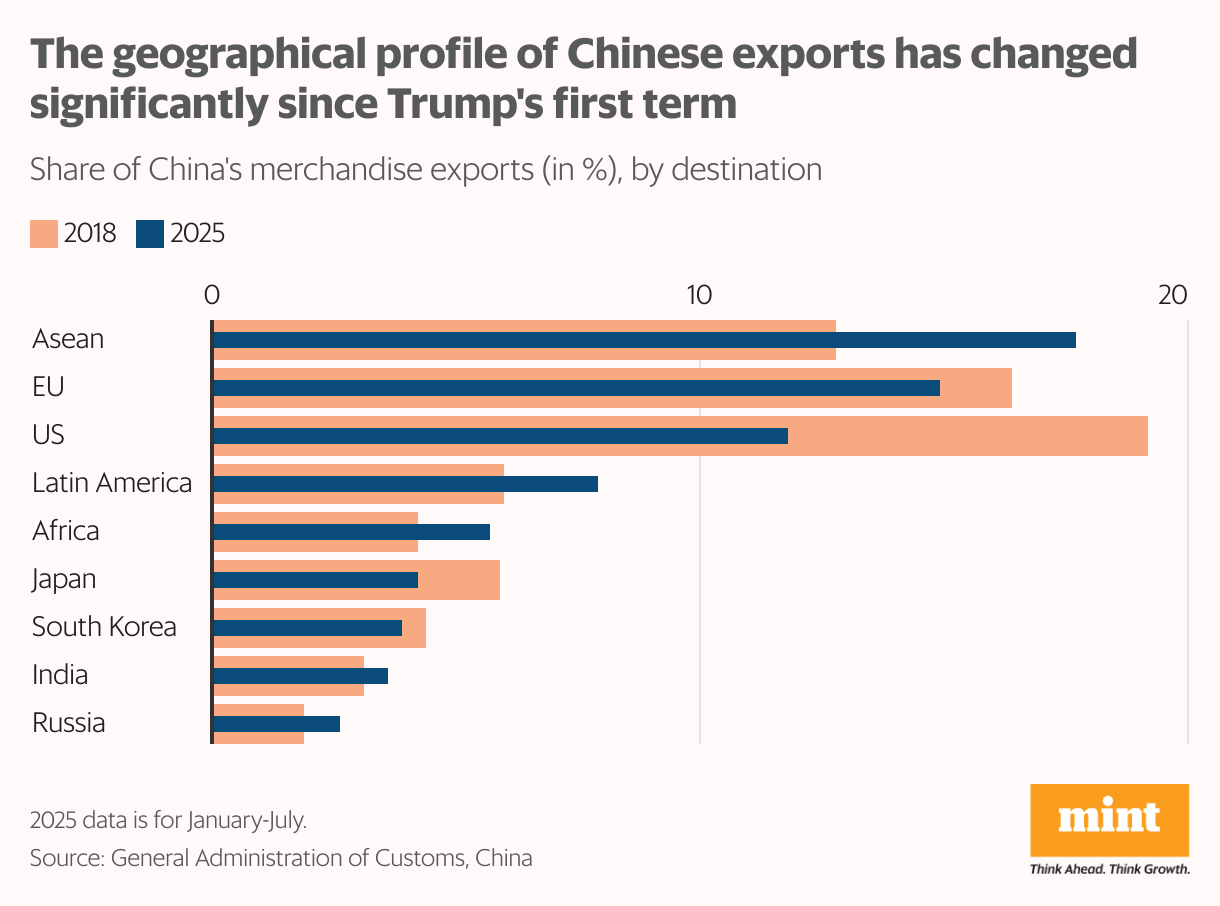

China’s core strategy was to reduce reliance on the US by diversifying into new export markets. Since 2018, the US’s share in China’s exports has declined by nearly eight percentage points. This was mostly set off by the increase in export shares of members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), Latin America, and Africa.

In Africa, China has established deep trade links by riding on the Belt and Road Initiative (all except one African nation has signed up for it in some form). The BRI modus operandi is as follows: China lends money to poorer nations for developing infrastructure and industrial zones. Chinese firms carry out the task of building projects and maintaining them. In return, China gains valuable natural resources or access to ports, and can introduce its products into African markets.

China’s influence on African consumption is the result of years of policy planning: cheap Chinese solar panels dominate Africa, Chinese company Transsion controls half of Africa’s smartphone market, and China accounts for more than 40% of Africa’s textile imports.

Latin America and Africa provide mineral and agricultural inputs; in return, they buy Chinese products. The added bonus? Given that most emerging market currencies have been depreciating against the dollar, trading partners are happy to use the Chinese renminbi to settle trades, thereby furthering Beijing’s ambition to internationalize the use of its currency.

Produce overseas

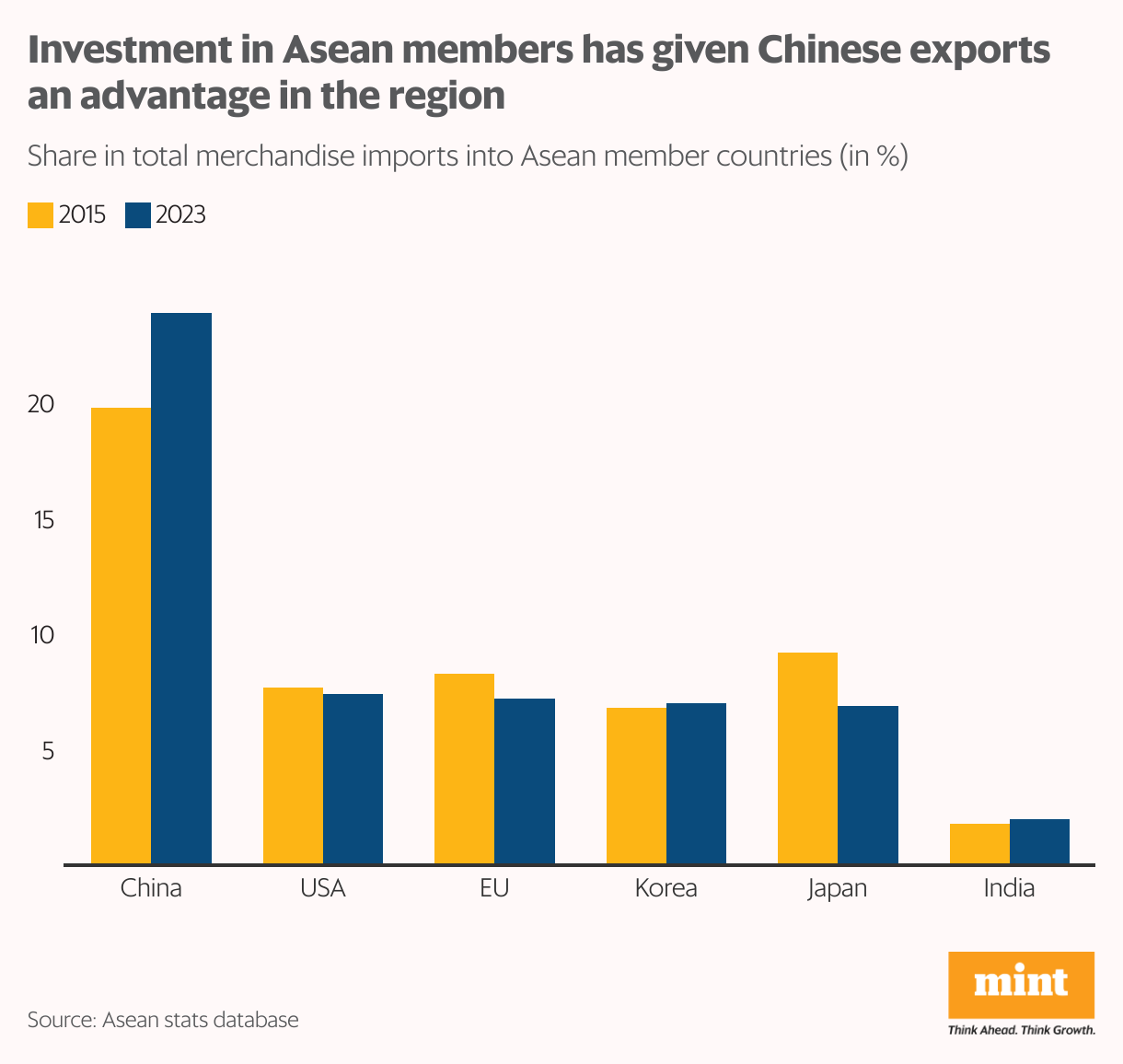

Here’s another strategic step that China has taken: investing heavily in production facilities in the Asean member countries. The initial motivation was to reduce costs, but since 2018, these locations have been used to re-route Chinese exports and evade US tariffs. Going forward, the adoption of stricter rules of origin is expected to reduce such transshipments. But exports to Asean member nations will continue to flourish for two reasons.

One, having manufacturing bases in the region is a huge advantage. A plant of Chinese conglomerate BYD in Thailand—which went operational in July 2024—has brought jobs to the host country, and also serves neighbouring high-growth markets. At present, BYD dominates new electric vehicle (EV) sales in Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore.

Two, over time, Chinese investments also lead to domestic value addition, thus creating a win-win situation for China as well as the host country. For instance, China is currently building a new BYD factory in Cambodia, while also developing EV charging infrastructure and training local workers with a view to building capabilities there.

Both these strategies seem to have paid off handsomely for Beijing: China now accounts for nearly a quarter of the total goods imported into Asean nations, up from around 20% just about a decade ago.

Adapt and innovate

But the key reason why China’s exports are resilient even in the face of current challenges is the ability of its companies to adapt and innovate.

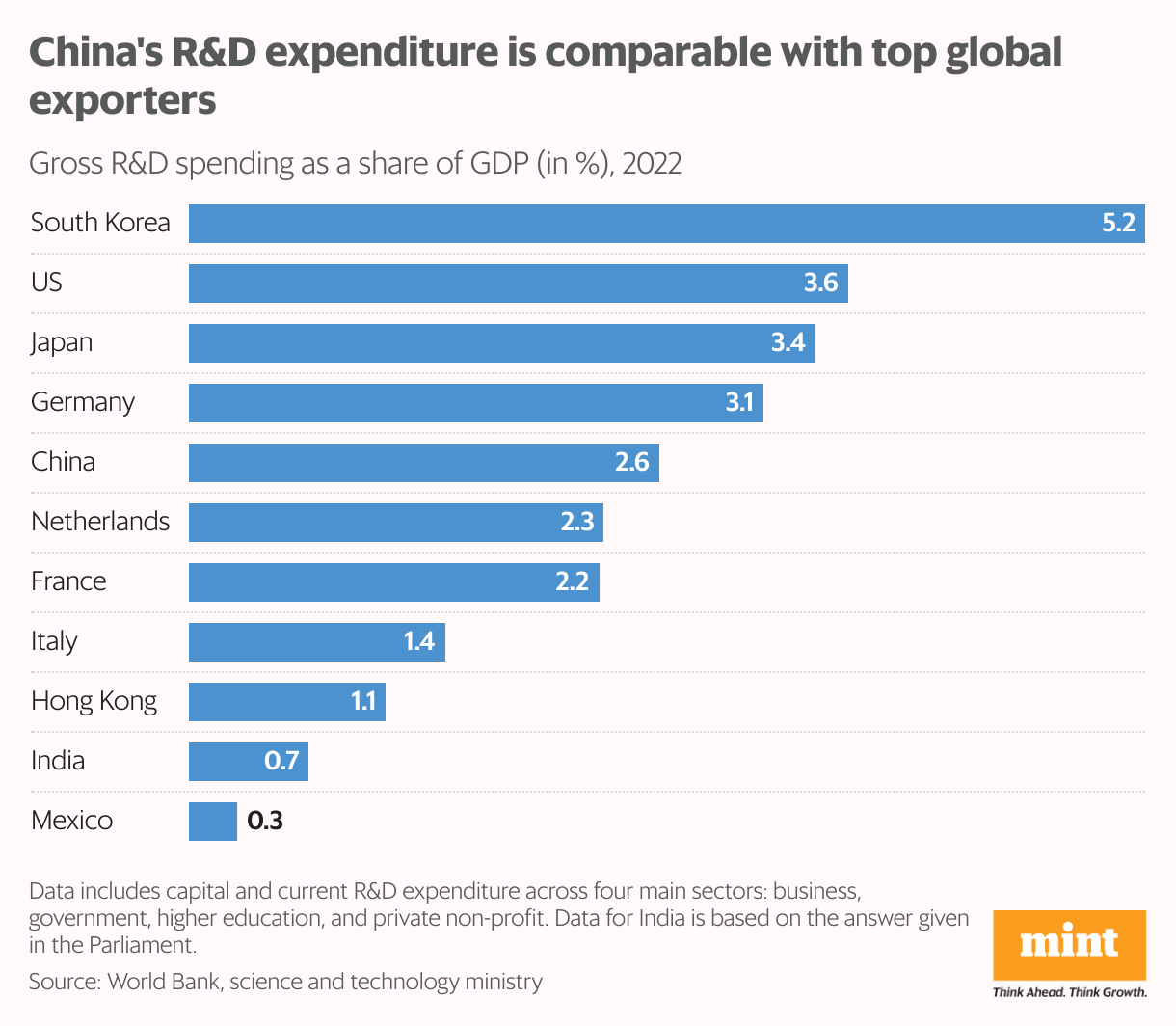

Studies show that innovation allows exporters to manage hostile economic environments because their products are state-of-the-art and high in quality, and remain in demand even in tough years. Innovation is more than entrepreneurial spirit—it is the outcome of expertise in research and development (R&D) and technological prowess.

The ability to innovate with the backing of research has propelled China from being a seller of cheap plastic goods to the developer of a pathbreaker such as DeepSeek, an artificial intelligence firm that took the world by storm last year. China’s gross expenditure on R&D is around 2.5% of GDP, comparable with the top exporting nations. Since 2015, China’s patent office has received over a million applications each year—in 2023, it issued 920,790 patents, the highest in the world.

Moreover, a new government anti-innovation campaign is urging businesses to avoid price wars and focus on quality and innovation—clearly, policymakers are aware of the critical role of R&D spending in securing future profitability.

What does all this mean?

In summary, China has developed a formidable export sector, which is keeping it afloat. It has a 14.5% share in global exports, well-entrenched in global supply chains, driven by innovation and productivity, with access to a wide range of markets, and showcasing a diverse array of products, ranging from Labubu dolls to rare earth metals. As Indian policymakers scramble to mitigate the impact of the US tariffs on India, there is much to learn from China’s journey of building resilience in exports.

The author is an independent writer in economics and finance.