The architect David Kroyanker, who penned dozens of books on Jerusalem’s urban landscape, died Saturday in his home at the age of 86.

Born and raised in Jerusalem’s Rehavia neighborhood to German Jewish parents, Kroyanker dedicated his life to documenting the city’s complex urban fabric and preserving its architectural heritage.

Though trained as an architect and planner, Kroyanker was best known for his written works chronicling the Jerusalem cityscape. He authored over 30 books and many more pamphlets and articles about the capital’s architectural heritage.

The researcher was a frequent campaigner to save the city’s historic structures from demolition during a period of rapid urban expansion in the capital, unified under Israeli rule after the 1967 Six Day War.

After completing his army service in the IDF Paratroopers Brigade, Kroyanker traveled abroad to study at London’s esteemed Architectural Association School of Architecture in the 1960s. Upon returning to Israel, he took up a job working for the renowned architect David Resnick.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

Kroyanker then began working in the Jerusalem Municipality’s urban planning department, where he remained for around a decade.

David Kroyanker as a Jerusalem city planner in 1971. (Courtesy)

While employed by the city, the architect railed against the demolition of the old building of the Talitha Kumi orphanage, established in the 19th century by German nuns in what is now Jerusalem’s city center.

Though the structure was eventually torn down in 1980, Kroyanker then led an effort to memorialize the building by erecting pieces of its original facade outside the new department store, which replaced it. The memorial today stands conspicuously, with its arched entrance and turret clock, between two bus stops.

Talitha Kumi (photo credit: Shmuel Bar-Am)

After leaving the municipality, Kroyanker transitioned to writing about Jerusalem’s architecture, authoring dozens of books filled with his sketches of buildings throughout the city, historic photographs and neighborhood plans.

His first major work was a six-volume series written over the span of a decade entitled “Jerusalem Architecture: Periods and Styles,” which covers the history of construction by Jews, Arabs and Europeans, examining why certain buildings and neighborhoods differ from one another.

In an interview with The Times of Israel, Kroyanker characterized the project by comparing the neighborhoods of Rehavia and Talibye, side-by-side and built more or less at the same time in the early 20th century.

While Rehavia was built by German Jews as a European-style garden suburb, neighboring Talbiye was full of ornate mansions built by well-to-do Arabs, “for whom showing off economic wealth was very important,” Kroyanker said. “By comparison, the Jews who built Rehavia, although some of them were also wealthy, were less interested in exhibiting their wealth.”

He received several awards for his decades of work, including the Teddy Kollek Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006, and Yakir Yerushalayim (“Worthy Citizen of Jerusalem”) in 2010.

Taking leave of Jerusalem

Despite his lifelong fascination with his birthplace, Kroyanker left Jerusalem in 2012 amid a large-scale flight of its urban, largely secular aristocracy — many of whom left due to the city’s increasingly religious character.

For Kroyanker, the decision to relocate was reportedly familial. Both of his daughters left the city as adults, and the scales finally tipped after his grandchildren were born, convincing Kroyanker to pack his things and bid farewell to the city he was raised in.

Though he insisted that he made his decision in light of his growing family outside the capital, Kroyanker often voiced discontent with the burgeoning influence of the city’s ultra-Orthodox population.

“If you ask me, it’s the number one problem in Jerusalem, and I think that what is winning in Jerusalem is demographics, and therefore I’m not particularly optimistic about its future,” he told Haaretz in 2010.

He also took issue with the new residential projects popping up in Jerusalem, many of which he said were built to serve a political agenda, with no concern for the capital’s urban character.

The Gilo neighborhood of Jerusalem, as it seen from Beit Jala in the West Bank, on February 16. 2025. (Wisam Hashlamoun/Flash90)

“I’m less happy with the architecture of the neighborhoods built after 1967, such as Ramot, Gilo, Pisgat Ze’ev, which were built almost solely for political reasons, mainly to prevent the division of the city in the future. All these neighborhoods were built on the basis of political decisions over which the Jerusalem Municipality had almost no control,” he said in the same interview.

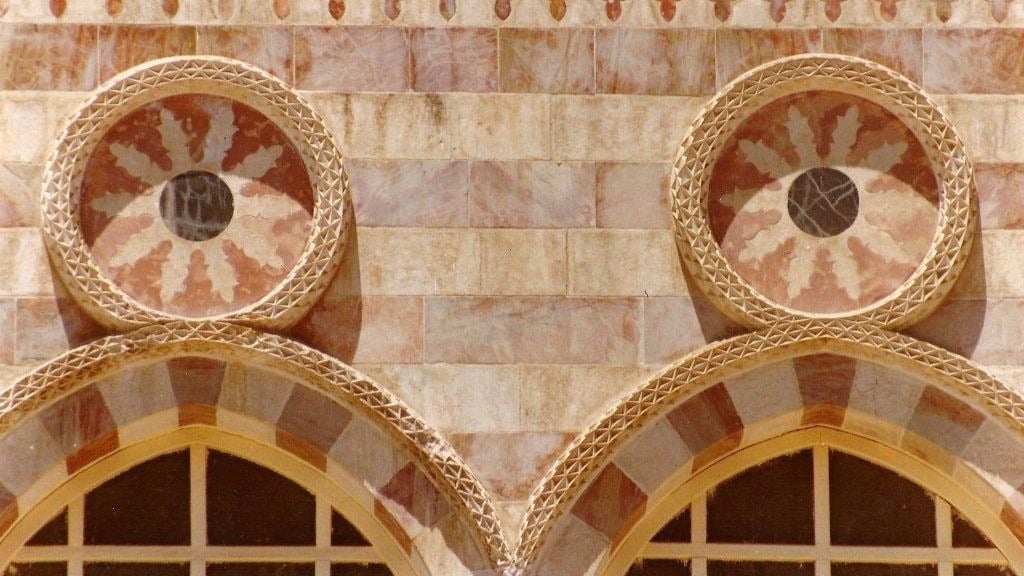

Kroyanker didn’t quit writing about his native Jerusalem after leaving, however. Five years after his departure, he wrote a four-volume set — “Jerusalem: God is in the Details” — focused on the minute designs that embellish Jerusalem’s historic buildings, from the Mamluk period until the end of the 20th century.

The work was a departure from his tendency to survey neighborhoods building by building, and focused instead on the “design identities” of the different nationalities, cultures, religious and ethnic groups that have built in Jerusalem for generations.

Muslim design identity (Courtesy)

The final book he published, titled “Jerusalem That Once Was” (2024), was meant to be his last work before his passing, in which he sought to conserve parts of the city’s built history that were destroyed, eroded or altered beyond recognition.

He noted with a tinge of sadness in the book the disappearance of Mandate-era architectural standards that shaped the city’s one-of-a-kind aesthetic: a ban on high-rise construction, building in valleys and a regulation stipulating that structures could only be made from Jerusalem’s native stone.

After he took leave of Jerusalem, Kroyanker confessed to The Times of Israel that he often missed taking strolls throughout the city.

The architect and writer David Kroyanker in Jaffa street at the center of Jerusalem September 2, 2005. (Yossi Zamir/ Flash90)

“I miss those days in which I would go to the Old City and walk the alleyways,” he said. “In Tel Aviv, I don’t go anywhere. I went once to [the gentrifying south Tel Aviv neighborhood] Florentin to look at the graffiti. Sometimes I do miss Jerusalem. To be honest, sometimes I do.”

Kroyanker is survived by two daughters and his grandchildren. His funeral was held Sunday at Kibbutz HaHamisha, located in central Israel.