Brussels – The upcoming elections in Moldova are described by several observers as the most crucial in the recent history of the young Balkan democracy. On Sunday, voters will stake the future of their country at the ballot box. In renewing the Parliament in Chișinău, voters will have to choose whether to remain on the pro-European path mapped out by the President of the Republic, Maia Sandu, or heed the opposition’s call to turn towards Moscow’s orbit.

Currently, no party or coalition appears to be able to secure an absolute majority in the 101-member assembly, which requires 51 seats. Virtually all polls paint a general picture of deep uncertainty and high fragmentation. An eventual stalemate would complicate negotiations to form an executive, risking paralysing the small but strategic Balkan country by leaving it particularly exposed to strong regional geopolitical tensions, and potentially mothballing the EU rapprochement as well.

The eve’s projections

On the one hand, Sandu’s Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), whose leading candidate is the Speaker of the House, Igor Grosu, is in free fall. After its dazzling success at the 2021 parliamentary elections, when it won 52.8 per cent of the vote and 63 seats, the main national pro-European force is now projected to receive between 34 and 48 per cent.

The President of the Moldovan Parliament, Igor Grosu (photo: Antoine Tardy via Imagoeconomica)

The President of the Moldovan Parliament, Igor Grosu (photo: Antoine Tardy via Imagoeconomica)

Voters are sceptical of the unfulfilled promises of the liberal-conservatives, especially with regard to dealing with the heavy economic impacts caused by the war in Ukraine and the failure to implement the reform agenda. The only thing that is certain, if these estimates are confirmed, is that PAS will lose the absolute majority it held in the outgoing legislature and will have to form a coalition to govern.

On the other hand, closely threatening PAS is the Patriotic Bloc (BEP), an electoral cartel comprising the socialists of the PSMR, the communists of the PCRM, the Heart of Moldova (PRIM), and the Future of Moldova (PVM). Altogether, this diverse alliance of left-wing forces—gathered behind the Socialist leader Igor Dodon, Sandu’s predecessor in the presidency of the Republic—could reach between 21 and 36 per cent of the preferences, vying for the top spot with PAS. BEP is pushing for a more “balanced” geopolitical approach: a closer rapprochement with Moscow, albeit without breaking ties with Brussels, and the strategic neutrality of Chișinău (which would thus remain outside NATO).

Other parties that tend to be pro-Russian are the Our Party (PN), led by Renato Usatîi and credited between 8 and 12 per cent of the vote, and the Alternative Bloc (BEA), another centre-left coalition, self-styled pro-European but indirectly linked to Bep, currently hovering around 7-8 per cent. Even if the multifaceted pro-Russian left-wing forces ultimately prevail, however, the road to forming a government would not necessarily be smooth. Dodon might have to step aside, leaving a third-party figure (perhaps a technician) in charge of the prime ministership and leading the executive action from the rear.

The leader of the PSRM, Igor Dodon (photo: Daniel Mihailescu/AFP)

The leader of the PSRM, Igor Dodon (photo: Daniel Mihailescu/AFP)

In fact, the accuracy of the polls is also limited by the fact that, in most cases, they do not account for the Moldovan diaspora. As was the case in last autumn’s elections, votes from abroad (around 8 per cent of the total) overturned what appeared to be solid results, thus tilting the balance in favour of Sandu and PAS in both the presidential rounds and the constitutional referendum on EU membership.

The geopolitical dimension

The stakes in these elections, rather than the leadership of the government, thus seem to be the very geopolitical trajectory of Moldova. According to analysts, this will be the most important vote since independence in 1991: on one plate is Chișinău’s path towards entry into the twelve-star club, on the other is the Balkan nation’s return to the Kremlin orbit, abandoned after Soviet domination.

The country has been an official candidate since June 2022, the political go-ahead for the start of accession negotiations dates back to December 2023, and the first intergovernmental conference with the Twenty-Seven was convened in June 2024, in parallel with that of Ukraine. Currently, there’s substantial progress, mainly in the areas of justice, anti-corruption, and dismantling the oligarchic structures inherited from the Soviet Union. However, given the informal coupling with that of Kyiv (over which Budapest’s veto remains in place), the Chișinău file also remains blocked, despite the EU executive considering both nations to be “ready” to open the Fundamentals Cluster.

The Balkan country is also crucial from a geostrategic perspective for Western support of Kyiv. Since the start of Russian aggression in 2022, it has hosted over 1.5 million Ukrainian refugees and currently provides protection to over 100,000 refugees. Above all, Moldova serves as a key base for the transfer of military supplies to the invaded country and also constitutes a vital hub for the transportation of grain products to and from Ukraine. Add to this the risks associated with Russia’s military presence in Transnistria, the pro-Kremlin separatist region.

Moscow Interference

For several months, and with increasing insistence in recent weeks, Sandu and its European allies have been sounding the alarm about the massive election interference campaigns orchestrated by the Federation to sabotage Sunday’s vote. Following the script already seen in the past year, not only in Moldova itself (where an estimated 130,000 votes were bought by Russia last autumn) but also in Romania and Georgia, Moscow is allegedly resorting to hybrid online and offline tactics, already widely known in Brussels.

In addition to traditional vote-buying, the Moldovan authorities reported a series of disinformation campaigns targeting both Brussels and PAS, including the use of artificial intelligence-generated content to personally discredit prominent pro-EU politicians. Fake websites artfully imitate real newspapers to spread pro-Russian propaganda and even fake government proclamations on the web, and even the Russian Orthodox Church seems to have mobilised.

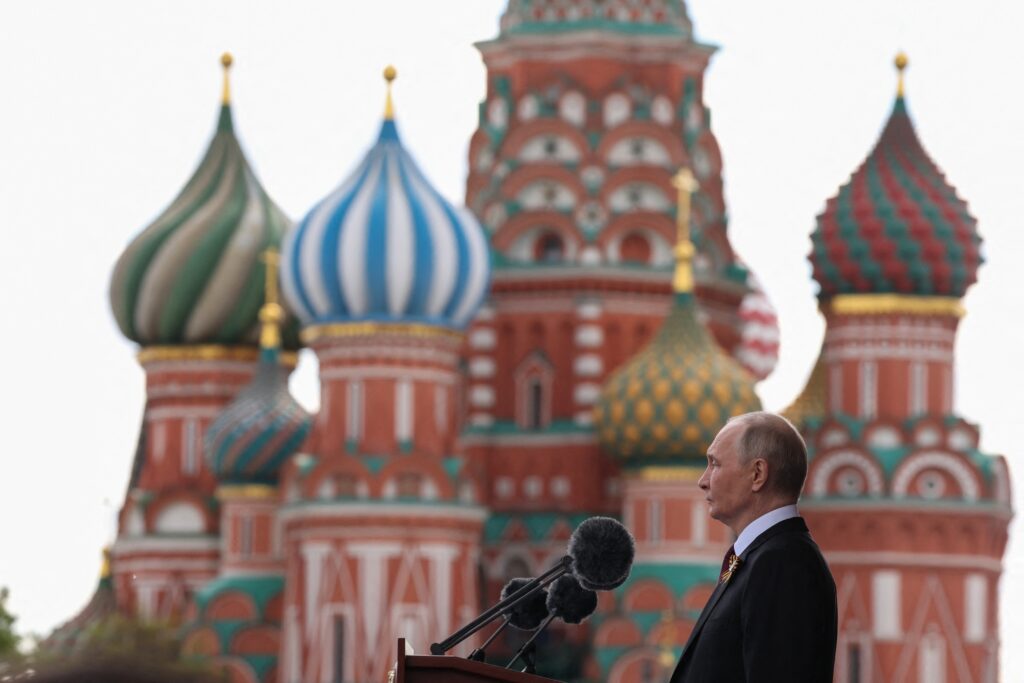

Russian President Vladimir Putin (photo: Vyacheslav Prokofyev/Sputnik via AFP)

Russian President Vladimir Putin (photo: Vyacheslav Prokofyev/Sputnik via AFP)

At the beginning of the month, Sandu invoked the EU’s support in front of the EU Parliament in defence of Moldova’s fragile democracy. At the end of August, a trio of heavyweights such as Emmanuel Macron, Friedrich Merz and Donald Tusk had visited Chișinău

to show symbolically the proximity of the Twenty-Seven. Just yesterday (24 September), Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky warned the UN General Assembly about the dangers of Russian electoral manipulation.

For the Liberal Renew group leader in Strasbourg, Valérie Hayer, “the future of Moldova lies in a strong and united EU.” “We stand by all Moldovans who defend their democracy,” she said, adding that “Russia’s attempts to interfere in Moldovan democracy are reprehensible and must have consequences.” According to her deputy, Dan Barna, “the EU must strengthen Moldova’s resilience and ensure the integrity of the vote.”

Berlaymont Foreign Affairs spokeswoman Anitta Hipper said this morning that Brussels places “full confidence in the Moldovan authorities” and guarantees “full support” to Chișinău, including through a new “European digital media monitoring hub” as well as the €1.9 billion provided under the Growth Plan for Moldova prepared by the EU in autumn 2024. “The EU is training, advising, and offering technical equipment” to the country, Hipper added.

English version by the Translation Service of Withub