The reefs, built by Desmophyllum pertusum, a slow-growing, cold-water stony coral, were healthier, larger, and richer with life than anticipated. One of the largest reef complexes was found at 300 meters depth and covered an area of 1.3 square kilometers—more than 180 FIFA football fields. The tallest mound measured 40 meters in height.

A sponge (Haliclona sp) atop a large mound of Desmophyllum pertusum, a slow-growing, cold-water stony coral species recently designated as vulnerable to extinction, documented at 269 meters deep. (Image credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute)

A sponge (Haliclona sp) atop a large mound of Desmophyllum pertusum, a slow-growing, cold-water stony coral species recently designated as vulnerable to extinction, documented at 269 meters deep. (Image credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute)

“We always expect to find the unexpected, but the diversity and complexity of what we found exceeded all our expectations,” said the expedition’s Chief Scientist, Dr. Alvar Carranza of the Universidad de la República and the Centro Universitario Regional del Este. Carranza and others had first detected the coral reefs in 2010 using mapping technology.

Blackbelly rosefish (Helicolenus dactylopterus) were documented among soft mushroom corals (Heteropolypus sp) at 246 meters deep off the coast of Uruguay. (Image credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute)

Blackbelly rosefish (Helicolenus dactylopterus) were documented among soft mushroom corals (Heteropolypus sp) at 246 meters deep off the coast of Uruguay. (Image credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute)

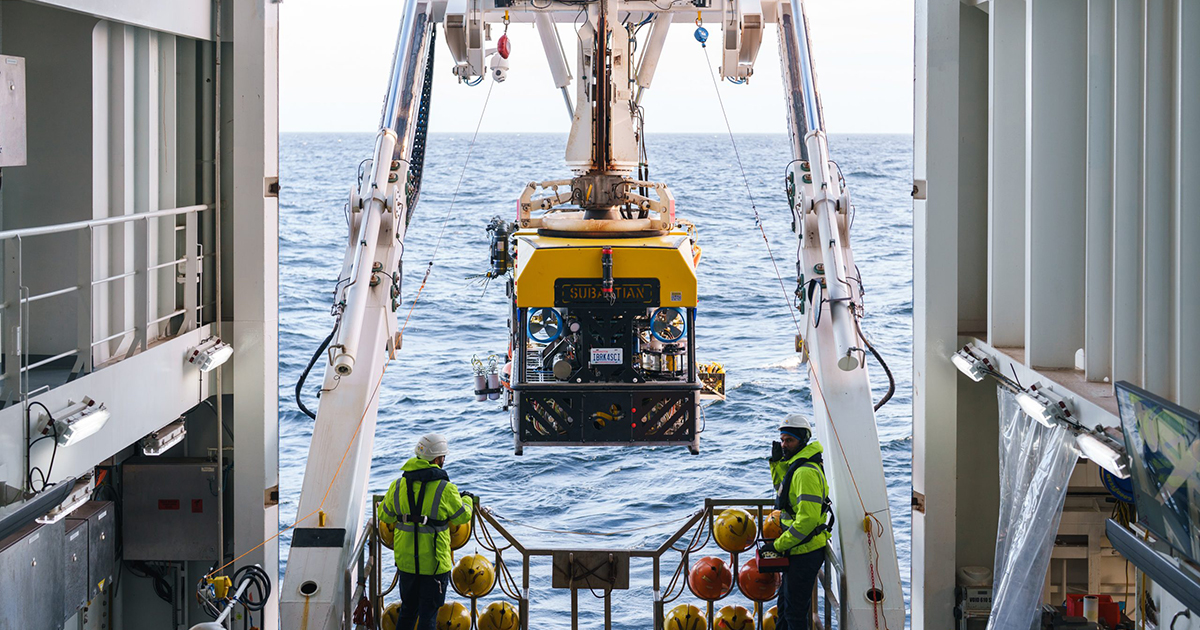

Using Schmidt Ocean Institute’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) SuBastian on board research vessel Falkor (too), the team observed a mix of both temperate and subtropical species, supported by warm and cold-water currents that meet off Uruguay’s coast. Colorful residents found living among the reefs included bellowsfish (also known as hummingbird fish), slit shell snails, groupers, and sharks.

A deep-sea catshark (Scyliorhinus haeckelii) documented at 198 meters on the outer edge of the continental shelf, near the head of the La Paloma submarine canyon. (Image credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute)

A deep-sea catshark (Scyliorhinus haeckelii) documented at 198 meters on the outer edge of the continental shelf, near the head of the La Paloma submarine canyon. (Image credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute)

The data collected from the expedition will guide how Uruguay’s marine resources are managed, Carranza said. While there is only one confirmed vulnerable marine ecosystem, or VME, in Uruguay at this time, the 29-day expedition provides evidence that more vulnerable areas exist. The team discovered at least 30 suspected new species, including sponges, snails, and crustaceans. They documented hundreds of species never before seen in Uruguayan waters, such as crystal squids, the dumbo octopus, and tripod fish.

They were also the first to explore the wreck of the ROU Uruguay, a cannon-class destroyer that initially served as the USS Baron during World War II. The United States transferred it to Uruguay in 1952, who used it for several decades as a patrol and training ship until sinking it as a Naval exercise in 1995. The science team spent a full day studying the wreck, which now serves as a reef habitat. They also collected data to better understand how the shipwreck has changed over time and assess the presence of any contaminants.

The research team explored the shipwreck of the ROU Uruguay underwater, collecting data on the cannon-class destroyer that now serves as a reef habitat. The ship, initially the USS Baron during World War II, was donated by the US to Uruguay in 1952 and sunk in 1995 as a naval exercise. (Image credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute)

The research team explored the shipwreck of the ROU Uruguay underwater, collecting data on the cannon-class destroyer that now serves as a reef habitat. The ship, initially the USS Baron during World War II, was donated by the US to Uruguay in 1952 and sunk in 1995 as a naval exercise. (Image credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute)

“Discovering marine life reveals the hidden depths of the oceans and transforms the way we perceive our world,” said team member Dr. Leticia Burone of the Universidad de la República Uruguay. “R/V Falkor (too)’s divestream capabilities allowed us to connect directly with the people of Uruguay and show them our discoveries in real-time.”

Chief Scientist Alvar Carranza from the Universidad de la República in Uruguay, along with members of the science team, narrates streaming deep-sea footage for audiences watching in Uruguay and around the world. (Image credit: Alex Ingle, Schmidt Ocean Institute)

Chief Scientist Alvar Carranza from the Universidad de la República in Uruguay, along with members of the science team, narrates streaming deep-sea footage for audiences watching in Uruguay and around the world. (Image credit: Alex Ingle, Schmidt Ocean Institute)

In another location they observed worms (Lamellibrachia victori) that live on cold seeps—areas where chemicals, such as methane, are emitted from the seafloor—growing adjacent to the reef mounds. These two communities survive on different energy sources. Deepwater corals rely on microscopic food from the water column, whereas the worms feed on chemical energy from the seafloor.

“We’ve seen glimpses of this relationship in the Gulf of Mexico, but I have not seen a more perfect visual example of the association,” said Dr. Erik Cordes, a deep-sea coral and seep expert who is a professor at Temple University and has led previous expeditions with Schmidt Ocean Institute. It is a natural part of the community’s biological evolution. “The reefs they discovered are incredible.”

The team also observed a sea snail called an ovulid feeding on gorgonian soft coral, which is a common image in tropical areas of the ocean; however, in these cooler waters, it is akin to finding a giraffe in Antarctica, said Carranza.

“This was Schmidt Ocean Institute’s 100th expedition and we are delighted that it took place in the beautiful waters off Uruguay with such an engaging team of scientists,” said Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Executive Director, Dr. Jyotika Virmani. “We were also honored that Uruguay’s President Yamandú Orsi graciously visited the vessel just before it set sail to wish the scientists and crew a successful voyage as they explored this previously never-before-seen part of the world.”

Research Vessel Falkor (too) sails off the coast of Uruguay. Data collected during the expedition will help inform how marine resources are managed and protected in Uruguayan waters. (Image credit: Alex Ingle, Schmidt Ocean Institute)

Research Vessel Falkor (too) sails off the coast of Uruguay. Data collected during the expedition will help inform how marine resources are managed and protected in Uruguayan waters. (Image credit: Alex Ingle, Schmidt Ocean Institute)