Justice Anthony Kennedy considered quitting the Supreme Court over abortion.

Kennedy, who served from 1988 to 2018, makes the revelation in a new book as he explains how he balanced his Catholic faith and ultimately cast the deciding vote in 1992 that saved abortion rights for the next three decades.

His writings and a recent book by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, a conservative Catholic who provided the key vote in 2022 to end a constitutional right to obtain an abortion, provide a rare window into personal conflicts regarding religion and the law.

Catholics have increasingly dominated the high court and prompted debate over how the justices’ faith influences their decisions. The books arrive at a larger moment in America as Christian nationalism appears to be growing and debate over faith and politics has escalated.

“Because of my ever-constant belief that life must be protected from the moment of conception,” Kennedy wrote in his book to be published on October 14, “I struggled with the idea that the Constitution should allow some choice to end a pregnancy.”

Kennedy says he was particularly torn during the 1992 case Planned Parenthood v. Casey, when the justices were deciding whether to affirm or reverse Roe v. Wade, the milestone that made abortion legal nationwide.

“The struggle led me to wonder whether it would be wrong for me, morally, to stay on the Court if doing so would require me to rule under the law that women have the right to end a pregnancy in its early, pre-viability stage,” Kennedy writes. “My conclusion, reached in private and without discussion with others, was to stay on the Court.”

Today’s Supreme Court, controlled by justices more solidly conservative than Kennedy, has permitted greater mixing of church and state, through a coach’s prayers at public school football games, government financing of sectarian education, and religious monuments on government land.

The court has also moved rightward on social policy issues imbued with a religious dimension, such as reproductive rights and LGBTQ rights. The latter will soon be tested again, when the court in October hears a dispute over state efforts to prohibit health care professionals from engaging in “conversion therapy” with minors to change their sexual orientation or gender identity.

The justices will also take up a challenge to state bans on trans athletes in school sports. (In a case earlier this year, as the right-wing majority let states ban puberty blockers and hormone therapy for youths seeking to transition to match their gender identity, Barrett suggested she opposed granting transgender identity the same anti-discriminatory protections that the Constitution provides based on race and sex.)

University of Virginia law professor Douglas Laycock, who has long focused on cases involving the First Amendment guarantees of religion, says people naturally wonder how the justices’ faith plays into their decisions.

“There’s lots of speculation about how religion is influencing them,” he said. “It’s always useful to know how they approach cases.”

Yet Laycock cautions that explanations may be shaded by a kind of wishful thinking. “These are people resolving what appear to be deep, internal conflicts,” he said.

Both Kennedy and Barrett, appointed in 2020 and still sitting, have been pivotal justices. Their new books and respective records demonstrate how much the court has changed over time on controversies that touch on religion.

Kennedy ended up casting the key vote to reaffirm the 1973 Roe v. Wade case, concluding the Constitution protected a right to abortion before viability, that is, the point at which a fetus can survive outside the womb. That was the law until 2022, when Barrett went in the opposite direction and provided the fifth vote to strike down Roe.

In “Listening to the Law,” published in September, Barrett defended her vote in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Center. While she writes about her Catholicism in the context of the death penalty, she avoids any mention of her faith as she explained why she rejected Roe.

Kennedy writes in his book that he disliked being described as the court’s “swing vote,” but the centrist conservative constantly made the difference in important cases. An appointee of President Ronald Reagan, Kennedy navigated between the right- and left-wing blocs, over time aligning more with the left on social issues.

“My colleagues knew, too, that religious and traditional family values had led me to feel some personal conflict over these matters,” Kennedy wrote as he discussed his votes on gay rights in “Life, Law & Liberty.” “Because my colleagues knew of these tensions, and the cases looked as if they would be closely divided, the opinions were assigned to me.”

On gay rights, Kennedy clashed most with fellow Catholic Antonin Scalia, with whom he served for nearly his whole time, until Scalia’s death in 2016. Kennedy reveals in his book that after the court’s 2015 opinion declaring a right to same-sex marriage, Scalia rarely spoke to him or attended the justices’ lunches.

Such differences between Kennedy and Scalia offer a reminder that the court’s conservative Catholics cover a range. There was an even greater difference with their Catholic colleague William Brennan, an unyielding liberal. Brennan sat from 1956-1990 and died in 1997.

In 1973 when Roe was decided, Brennan was the only Catholic on the Supreme Court. “I wouldn’t under any circumstances condone an abortion in my private life,” he said, according to a 2010 Brennan biography by Seth Stern and Stephen Wermiel. “But that has nothing to do with whether or not those who have different views are entitled to have them and are entitled to be protected in their exercise of them. That’s my job in applying and interpreting the Constitution.”

There are now six justices on the right wing who are either practicing Catholics (Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh and Barrett) or were raised Catholic (Neil Gorsuch, now an Episcopalian). A seventh Catholic justice, Sonia Sotomayor, firmly resides on the liberal wing.

Among those current Catholics, Alito has been most outspoken in his views. He has headlined Catholic-sponsored events and regularly contends that religion is under siege.

Last year in a speech to graduates of Franciscan University of Steubenville in Ohio, he said, “Freedom of religion is also imperiled. When you venture into the world you may well find yourself in a job or a community or a social setting when you will be pressured to endorse ideas you don’t believe, or to abandon core beliefs. It will be up to you to stand firm.”

Barrett says in her book that she was surprised her Catholicism was raised in a 2017 hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, when President Donald Trump first nominated her for a seat on a Chicago-based US appellate court.

Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein referred to the writings of Barrett, who was then a University of Notre Dame law professor. “The conclusion one draws,” Feinstein said, “is that the dogma lives loudly within you. And that’s of concern when you come to big issues that large numbers of people have fought for, for years in this country.”

Some Republican senators said Barrett had been wrongly confronted with a “religious test,” and even Feinstein’s Democratic colleagues thought she had awkwardly raised the issue. (For her 2020 Supreme Court hearing, Democratic senators largely avoided questions involving religion or her association with the Christian group People of Praise.)

In her book, Barrett writes, without naming Feinstein, who has since died, “Some suggest that people of faith have a particularly difficult time following the law rather than their moral views. (I faced that criticism as a Catholic, most sharply when the Senate Judiciary Committee conducted a hearing to consider my nomination to the Seventh Circuit.) I’m not sure why.”

She then adds, “Fortunately for the health of our country, people of faith are not the only Americans with firm convictions about right and wrong. Nonreligious judges also have deeply held moral commitments, which means that they too face conflicts between those commitments and the demands of the law. A secular humanist who passionately believes that access to abortion is a moral imperative must set aside her views, no less than the judge whose faith informs a moral objection to abortion.”

Barrett referred to her personal opposition to capital punishment and her votes to uphold the death penalty.

“For me, death penalty cases drive home the collision between the law and my personal beliefs,” she writes. “Long before I was a judge – before I was even a member of the bar – I co-authored an academic article expressing a moral objection to capital punishment.”

She then noted that she cast a vote in 2022 with the majority to reinstate a death sentence for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, convicted in the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

“Swearing to apply the law faithfully means deciding each case based on my best judgment about what the law is,” she writes. “If I decide a case based on my judgment about what the law should be, I’m cheating.”

Both Barrett and Kennedy make clear that their Catholicism is central to their personal identities. Kennedy ended up aligning less with church teachings.

At the time he was conflicted over his Catholicism and abortion rights, Kennedy concluded: “To resign in effect would have been to say that the judicial oath to protect constitutional rights is not binding in difficult or controversial cases. And as a practical matter, in those times, it was possible that my successor would be less concerned about protecting the unborn.”

Scalia and gay rights

Kennedy suggests that his decisions favoring gay rights came with less anguish. But this is where he fought with Scalia, a fellow Catholic of the same generation (both were born in 1936) and similarly appointed by Reagan.

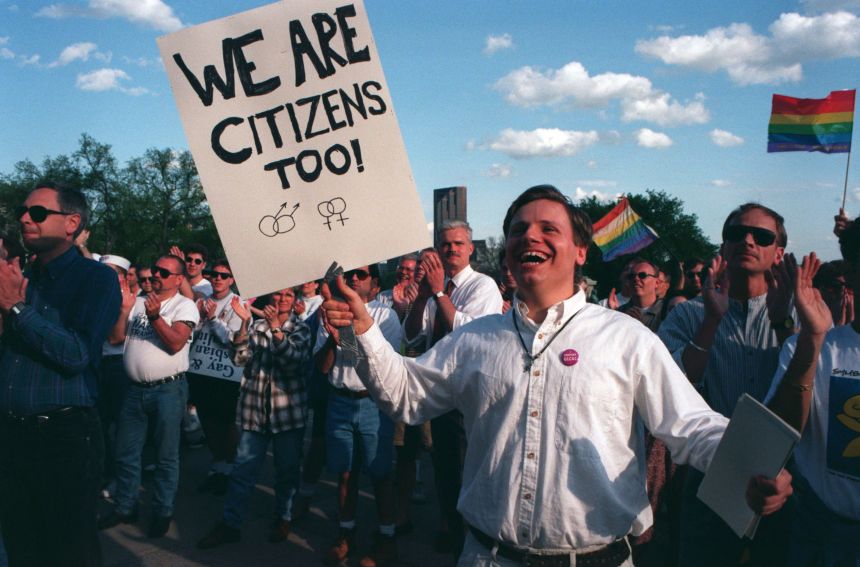

When Kennedy authored his first major opinion favoring LGBTQ interests, in a 1996 case that struck down a Colorado state ballot initiative that prevented localities from protecting gay and lesbian rights, he was startled by Scalia’s dissenting views.

The Kennedy majority had said the voter initiative violated the constitutional guarantee of equal protection and had seemed “inexplicable by anything but animus.”

Scalia countered in his dissenting opinion, “This Court has no business imposing upon all Americans the resolution favored by the elite class from which Members of this institution are selected, pronouncing that ‘animosity’ toward homosexuality is evil.”

In his new book, Kennedy writes, “The vehemence of the dissent – and of Justice Scalia’s dissents in later cases on the subject – truly surprised and disappointed me and a number of my colleagues.”

About two decades after that ruling in Romer v. Evans, their relations worsened when Kennedy crafted the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges decision allowing same-sex marriage nationwide and Scalia penned a harsh dissent.

“After Obergefell was announced in June and our new session began in October, Nino rarely came to lunch with us or stopped by to chat,” Kennedy writes, adding that his children were upset by the dissent’s “rare personal attack” on Kennedy.

Then in early February 2016, Scalia visited Kennedy in his chambers. Referring to Scalia by his nickname, Kennedy wrote, “Nino said he had come to regret deeply the tone of his Obergefell dissent and its personal references. He apologized for being intemperate. We both smiled, and the matter was resolved.”

Scalia was about to leave for a hunting trip in Texas.

Kennedy recalled him saying, “Tony, this is my last long trip.” Scalia died a little over a week later while on that trip.

“Those parting words were the last we ever spoke to each other.”