In our study, we analysed trends in the incidence of seminoma and non-seminoma testicular cancer in Latvia from 1994 to 2017. We observed similar incidence and mortality trends as those reported in Scandinavian, Western European and other Baltic countries. Furthermore, increasing survival rates were observed.

Testicular cancer incidence remains highest in Northern Europe, with age-standardized rates of 11.7 in Norway and 11.2 per 100,000 individuals in Denmark [3, 16]. However, trends show only modest increases, with an APC of 2.4% (95% CI: 2.0–2.8) in Norway and 0.8% (95% CI: 0.4–1.3) in Denmark, indicating relatively stable patterns [3].

In contrast, countries in Central and Eastern Europe, where incidence rates are lower, have shown more pronounced increases, with APCs ranging from 3 to 5%. Our analysis revealed a similar trend in Latvia, with an incidence of 3.57 per 100,000 and an APC of 2.37% (95% CI: 0.78–3.94). Comparable results were observed in Lithuania (incidence 3.45 per 100,000; APC 2.97%, 95% CI: 0.9–5.1) [17,18,19,20].

This study demonstrates a five-year survival rate of 76% for Latvia, which is comparable to neighbouring countries—67% in Lithuania and 74.5% in Estonia [5, 11]. Our analysis also revealed a positive trend over time, with five-year survival increasing from 68.8% in 2000–2009 to 80.9% in 2010–2017, what reflects advancements in both treatment and diagnostic strategies. In a study conducted by Trama et al. based on EUROCARE-5 data, it was found that the five-year relative survival rate for patients with testicular cancer was 89% [19]. However, when considering age-standardized five-year survival rates across different parts of Europe (Northern, Central, Southern, and Eastern), the rate ranged from 80 to 92%.

Our findings indicate that survival curves for testicular cancer patients stabilized approximately 2–3 years post-diagnosis, suggesting durable long-term survival. Notably, five- and ten-year survival rates were nearly identical, differing by only around 5%.

This phenomenon suggested that once patients surpassed the initial critical period following diagnosis and treatment, the long-term survival outlook remained relatively consistent between the five-year and ten-year follow-ups. This finding underscores the importance of early detection and effective treatment for improving the overall prognosis of individuals diagnosed with testicular cancer.

Gurney et al. reported that in the majority of countries with available histological data, there was a higher incidence of seminoma than non-seminoma. Furthermore, both types of testicular cancer showed an increasing trend over time. The proportion of seminomas in Latvia is 56%, which is consistent with trends observed in Central European countries and slightly higher than in neighboring countries—46% in Lithuania and 37% in Estonia, respectively [17, 19,20,21,22,23]. Although both types have demonstrated upward trends in several high-incidence countries, seminomas have sometimes increased at a faster pace [3].

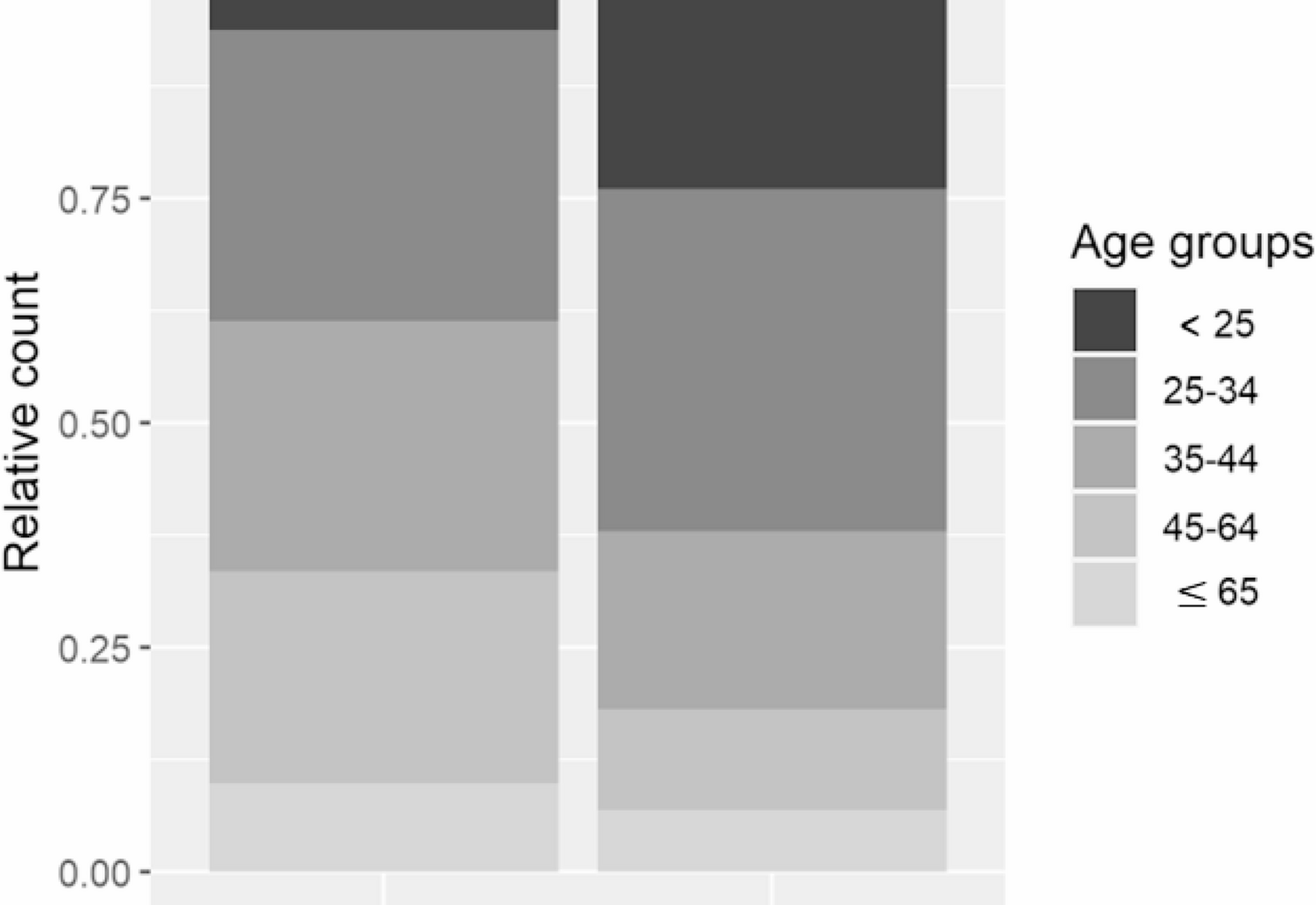

Regarding temporal patterns, seminoma and non-seminoma incidence rates have generally followed similar trends. However, some high-incidence countries show slight divergence in recent years [24]. In our analysis, both subtypes increased, with APCs of 4.1% (95% CI: 0.48–5.2) for seminomas and 3.18% (95% CI: 0.42–5.9) for non-seminomas. These trends are consistent with patterns observed in neighboring and other European countries [17, 19, 21] and confirm European data that seminomas are typically diagnosed around 10 years later (ages 35–40) than non-seminomas (around age 25) [3].

The observed age differences between seminomas and non-seminomas may be explained by distinct tumour biology. Non-seminomas typically demonstrate more aggressive behaviour, rapid progression, and a higher likelihood of metastatic presentation at diagnosis, contributing to their earlier age distribution [25].

Trama et al. reported five-year relative survival rates in Europe of 93.9% for seminoma and 88.3% for non-seminoma, underscoring the prognostic impact of histology [19]. The highest survival rates were observed in Northern Europe, reaching 97.7% for seminoma and 90.2% for non-seminoma.

In our study, we observed that the five-year cancer-specific survival rates were lower than reported in other countries and regions, 81% for seminomas and 76% for non-seminomas. These outcomes are also less favourable compared to Lithuania, where the five-year survival rates were 93.98% and 87.94%, respectively [21].

In our study, the majority of testicular cancer cases were observed among individuals from rural areas, aligning with findings by Sonneveld et al. [26]. While various environmental and hormonal factors have been proposed, only a few have shown consistent associations with increased testicular cancer risk [27]. This location pattern may be explained by a relatively high frequency of shared genetic traits among individuals with common ancestry in these regions, including genes potentially associated with testicular cancer susceptibility. While definitive causal relationships for many environmental exposures remain unconfirmed, prenatal exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals—such as pesticides (e.g., DDT), phthalates, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and bisphenol A (BPA)—is currently not considered a major concern in Latvia, given the country’s predominantly agrarian structure and limited industrial activity involving these substances [28, 29].

In our study, five-year cancer-specific survival was higher in rural areas compared to urban areas, at 78% and 69% respectively. This contrasts with findings from neighbouring countries such as Belarus, where survival rates were reported at 79% in urban areas and only 59% in rural areas [30]. Previous research on genitourinary tract cancers has suggested that better access to medical services in urban settings typically correlates with improved survival outcomes [31,32,33,34].

One possible explanation for the observed trend in Latvia may be the effectiveness of national healthcare programs that ensure timely access to diagnostics and treatment for cancer patients, even in rural areas. Additionally, rural environments may offer cleaner ecological conditions with lower exposure to environmental risk factors, which could positively influence cancer progression and survival.

Identifying early trends in rural versus urban cancer outcomes is important for designing targeted healthcare interventions. This is particularly relevant for underserved or vulnerable populations, where access to timely care may be inconsistent. Focused public health strategies can help reduce disparities and improve cancer survival across different geographic regions.

As demonstrated in our study, better survival rates were observed in younger age groups, particularly those under 45 years, with a five-year survival rate of 82.1%, consistent with findings by Møller et a l [25]. This aligns with the EUROCARE-5 data, which reported a five-year relative survival rate of 96.5% for individuals aged 15–39 years and impressive 90% for individuals older than 40 years [19].

The analysis by Fossa et al. presented intriguing findings, revealing an adverse impact of increasing age on testicular cancer-specific mortality [35]. The researchers proposed a hypothesis suggesting that the combination of reduced treatment intensity and heightened therapy-related toxicity might be a plausible explanation for the increased testicular carcinoma-specific mortality in patients older than 40 years. This study sheds light on the complex interplay of various factors that can influence the prognosis of older individuals with testicular cancer.

Physiological decreases in bone marrow capacity and kidney function [36], as well as a greater incidence of life-threatening conditions, such as second malignancy and cardiovascular disease, are observed among individuals who have survived testicular cancer than in the general population [37, 38].

The variation in five-year relative survival rates between our study and other Nordic and Baltic countries indicates that a meticulous analysis of the situation should be conducted. Several potential factors may explain these differences. One significant aspect is the presence of diagnostic uncertainty, which may result from limited access to advanced diagnostic tools. Additionally, the accessibility of urologists, particularly outside major cities, could contribute to delayed medical consultations and diagnoses. A concerning finding from our study is that nearly half of the patients presented with metastatic disease in clinical stage II and III, shedding light on the importance of early detection and prompt medical intervention.

Testicular cancer, a rare and malignant neoplasm, accounts for only 5% of all urologic diseases, with approximately 30 cases reported annually in Latvia. These patients are dispersed across various hospitals, leading to potential variations in treatment approaches and sometimes inadequate time intervals between diagnosis and treatment, especially for those with metastatic disease. Numerous studies emphasize the importance of centralizing the treatment of rare pathologies in a single clinical centre, where a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach can be employed. Such an approach ensures that patients receive standardized and optimal care, enhancing their chances of better outcomes and improved quality of life. The need for a more unified and coordinated approach for managing testicular cancer patients is paramount, and it underscores the significance of centralizing care to achieve the best possible results [39,40,41].

Since the introduction of cisplatin-based medicine for the treatment of testicular cancer, this once formidable disease has transformed into one of the most curable types of cancer. In developed countries, remarkable progress has been made in improving surveillance, leading to impressive five-year survival probabilities of up to 95% and a significant reduction in cancer-specific mortality. However, our study, which focused on Latvia, reveals a contrasting observation. Despite advancements in surveillance and treatment, the mortality rate in Latvia has not significantly changed. The average annual percentage change in the APC was 1.32 (95% CI −1.525 to 4.2) for cancer-specific mortality in Latvia.

Therefore, it is crucial to conduct long-term monitoring and follow-up of testicular cancer survivors. Population-based cancer registries can serve as valuable resources for conducting survivorship studies to better understand the health outcomes and long-term effects of testicular cancer and its treatments [42].

The imperative to enhance information, popularize the topic on social media, and improve education on cancer risk groups and self-examinations is of utmost importance—particularly for young boys and their parents—as it may contribute to earlier tumor detection. As stated in the insightful study McGuinness et al. [43], increasing awareness about cancer risk factors and empowering individuals with knowledge about self-examinations can be instrumental in early detection and prevention efforts. This concerted effort to improve awareness and education can pave the way for a healthier and more informed generation. Additionally, the education of general practitioners and the increased availability of testicular ultrasound in smaller hospitals and outpatient clinics—particularly in regions outside the capital—can ultimately contribute to earlier detection, improved cancer outcomes, and enhanced overall well-being.