Tuesday 30 September 2025 5:19 am

| Updated:

Monday 29 September 2025 2:45 pm

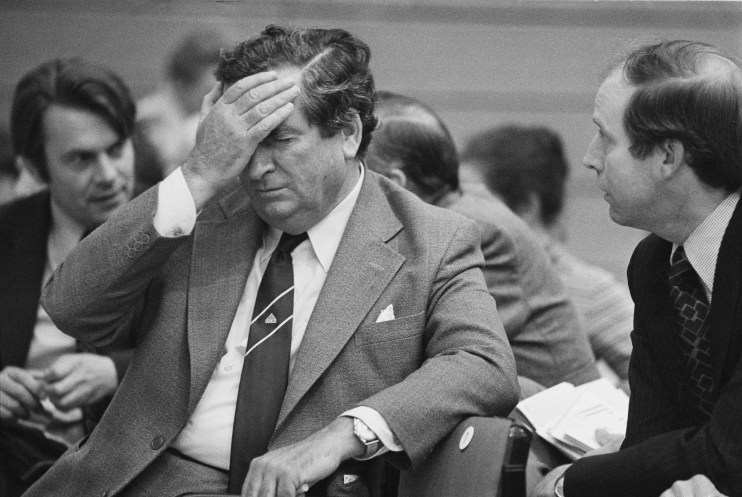

English Labour Party politician and Chancellor of the Exchequer, Denis Healey (1917 – 2015) at the Labour Party Conference in Brighton on 3rd October 1977. (Photo by John Williams/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

English Labour Party politician and Chancellor of the Exchequer, Denis Healey (1917 – 2015) at the Labour Party Conference in Brighton on 3rd October 1977. (Photo by John Williams/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

49 years ago today, sterling crashed to its lowest ever point against the dollar. Denis Healey stared down his socialist opponents and asked the IMF for a loan – paving the way for Margaret Thatcher’s election victory, writes Eliot Wilson

Denis Winston Healey, chancellor of the Exchequer (1974-79) and Labour’s indomitable intellectual brawler, soaked up pressure like few politicians could. At 26 he had been beach master for the 2nd Infantry Brigade during the Anzio landings, getting thousands of soldiers ashore in the middle of the night. He read Plato and Kant, but once warned a patronising admiral he would “chew his balls off”.

Even for Healey, though the last few days of September and the beginning of October 1976 would be challenging.

On 28 September, Healey was in the VIP lounge at Heathrow, preparing to fly to Hong Kong for a meeting of Commonwealth finance ministers, then to the International Monetary Fund’s annual meeting, taking place in Manila. The British economy was mired in problems: inflation was 14.5 per cent (though down from a high of 23.7 per cent earlier in the year); the balance of payments deficit was ballooning at more than £2bn; and Britain’s foreign exchange reserves were at a record low of just over $5bn.

Most alarming was the collapsing value of sterling. At the beginning of the year a pound was worth $2.20, but that figure had tumbled and by September the two currencies were much more evenly weighted, with $1.69 to the pound. The value had dropped by another two cents the preceding day, and as Healey enjoyed the airport lounge, more bad news reached him. Sterling had fallen yet again, and was now at $1.63, its lowest ever value against the dollar.

Healey acted decisively: he abandoned his journey and returned to the Treasury on Horse Guards Road. He knew how serious the crisis was. The government had been running a fiscal deficit of 10 per cent of GDP, and the cabinet could not agree on meaningful reductions in public expenditure. Over the next months foreign loans amounting to $18bn were due for repayment, and the usual institutional investors had stopped buying government debt. Britain had run out of credit.

The government was also foundering. Jim Callaghan, recently installed as Prime Minister, was leading a minority administration with very little internal unity. Joel Barnett, the puckish, sharp-minded Jewish accountant who was Healey’s deputy, later wrote that “there is no comparable example of such intellectual and political incoherence in a Party coming to office in the 20th century history of the United Kingdom”.

Healey and Callaghan had reached a momentous decision. At the IMF meeting, the Chancellor had planned to apply for a loan of $3.9bn, at that point the biggest the IMF had ever considered. With sterling virtually in freefall, Britain desperately needed liquidity.

Spending cuts

Back in London, Healey resolved to march towards the sound of gunfire. Forty-nine years ago today, on Thursday 30 September 1976, the Chancellor flew to Blackpool to make his case to the Labour Party Conference. He knew the left-wing delegates would instinctively hate the idea of being a supplicant to the mavens of international finance, and would fear the conditions that might come with the money. The IMF, at that point run by a liberal Dutch economist (who, oddly, was a practising Sufi) would expect cuts in spending.

Healey had been voted off Labour’s National Executive Committee the previous year by party members who wanted stronger socialist economic policies, so had to wait to be called from the floor to speak. He had sat through speeches denouncing “people who control the world’s capital”, and calls for massive export controls and a siege economy. But Healey was a man to bring a bazooka to a knife fight.

“I do not come with the Treasury view,” he began boomingly. “I come from the battlefront.”

His case was simple. He would negotiate with the IMF on the basis of existing government economic policies. But the party had to get behind those policies, because any other course of action “would mean a Tory government”. He was withering about the preceding speakers.

“I have never heard of a siege economy in which we stop imports coming in and demand total freedom for exports to go out. That is the sort of siege economy some of our critics are asking for… it would be a recipe for a trade war and a return to the conditions of the Thirties. Do you think that would be of advantage to any of us?”

Some delegates booed and heckled but the conference backed the government. The loan was agreed by December, of such a size that the IMF itself had to borrow money to fund it, and Healey kept the lights on for the government. Spending cuts, wage controls and junking a destructive wealth tax saw inflation and unemployment begin to fall, and the government had repaid the loan in full by 1979. It was not quite monetarism avant la Femme de Fer, but the Labour left would never forgive Healey for his ‘betrayal’.

By September 1978, the economy was recovering and Callaghan was expected to call an election. Labour was periodically ahead in the opinion polls, and might have won. Callaghan and Healey would have been heroes. But the Prime Minister delayed, hoping for greater economic recovery. Instead he got the Winter of Discontent, lost a confidence vote and was defeated by Margaret Thatcher. Labour would be in opposition for the next 18 years.

What was it Healey had told the Labour conference? “There would be a Tory government, and we know the Tory alternative.” He was right.

Eliot Wilson is a writer

Share

Facebook Share on Facebook

X Share on Twitter

LinkedIn Share on LinkedIn

WhatsApp Share on WhatsApp

Email Share on Email