ASTANA — Once the world’s fourth-largest inland sea, the Aral Sea has become a global symbol of ecological disaster, said Dr. Sarah Cameron, associate professor of history at the University of Maryland, speaking at Nazarbayev University on Sept. 24.

Dr. Sarah Cameron, associate professor of history at the University of Maryland, speaking at Nazarbayev University on “Elusive Water: The Life and Death of Central Asia’s Aral Sea” on Sept. 24. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

Visiting Astana to exchange views and engage with students, she said that the sea’s collapse left enduring human and environmental consequences and continues to resonate in today’s global water crises.

Cameron, a historian focusing on Russia and the Soviet Union whose research spans genocide, environmental history and the societies of Central Asia, is working on a book titled “Elusive Water: The Life and Death of Central Asia’s Aral Sea.” She examines the causes and consequences of the Aral Sea disaster by centering the voices of the people who lived along its shores and depended on it.

She noted that while often framed as a Soviet-era case of mismanagement, the disaster continued after 1991 and now intersects with climate change, leaving a legacy of economic dislocation, cultural loss and persistent health concerns.

“If you talk to people in the region, it becomes clear that the disaster was a human catastrophe in addition to an environmental one. It encompasses things like economic devastation, cultural destruction, and sweeping impacts on human health,” said Cameron.

From abundance to collapse

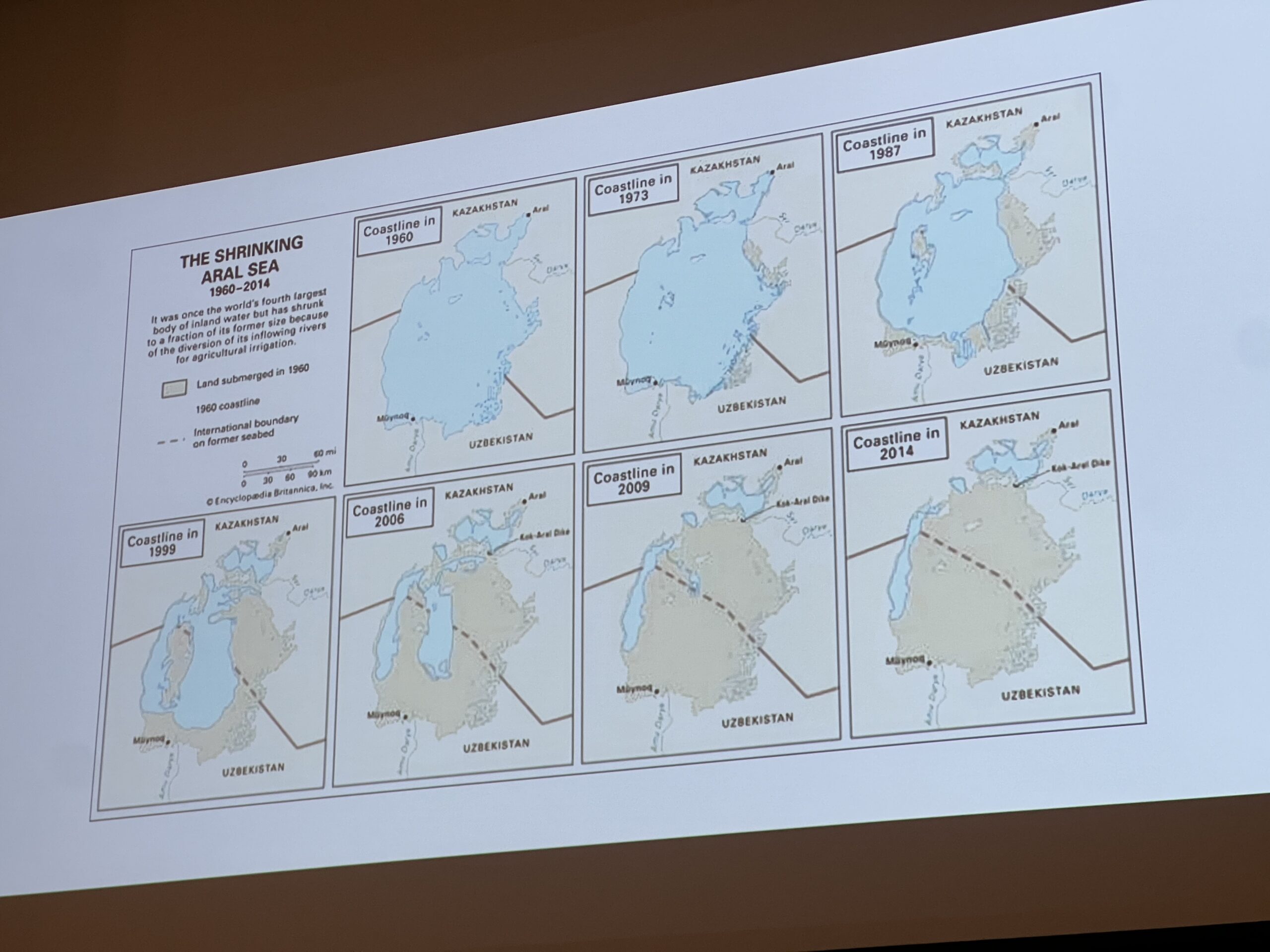

The Aral Sea was sustained for centuries by two great rivers, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya. Its waters supported vibrant fishing communities and unique ecosystems. That balance collapsed in the 1960s, when Soviet authorities diverted the rivers to expand cotton production.

Presentation by Dr. Sarah Cameron. The shrinking Aral Sea maps. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

“It is at this point that the climate and ecology of the sea begin to change. We get dust storms. The region begins to run out of water. People in the region begin to suffer from health problems. Prior to the 1960s, the Aral Sea had been Central Asia’s most important fishing body. But with the sea’s demise, fishing really collapses,” said Cameron.

In 2017, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres described the disappearance of the sea during a visit to Uzbekistan as the “biggest ecological catastrophe of our time.”

Competing narratives of the Aral Sea

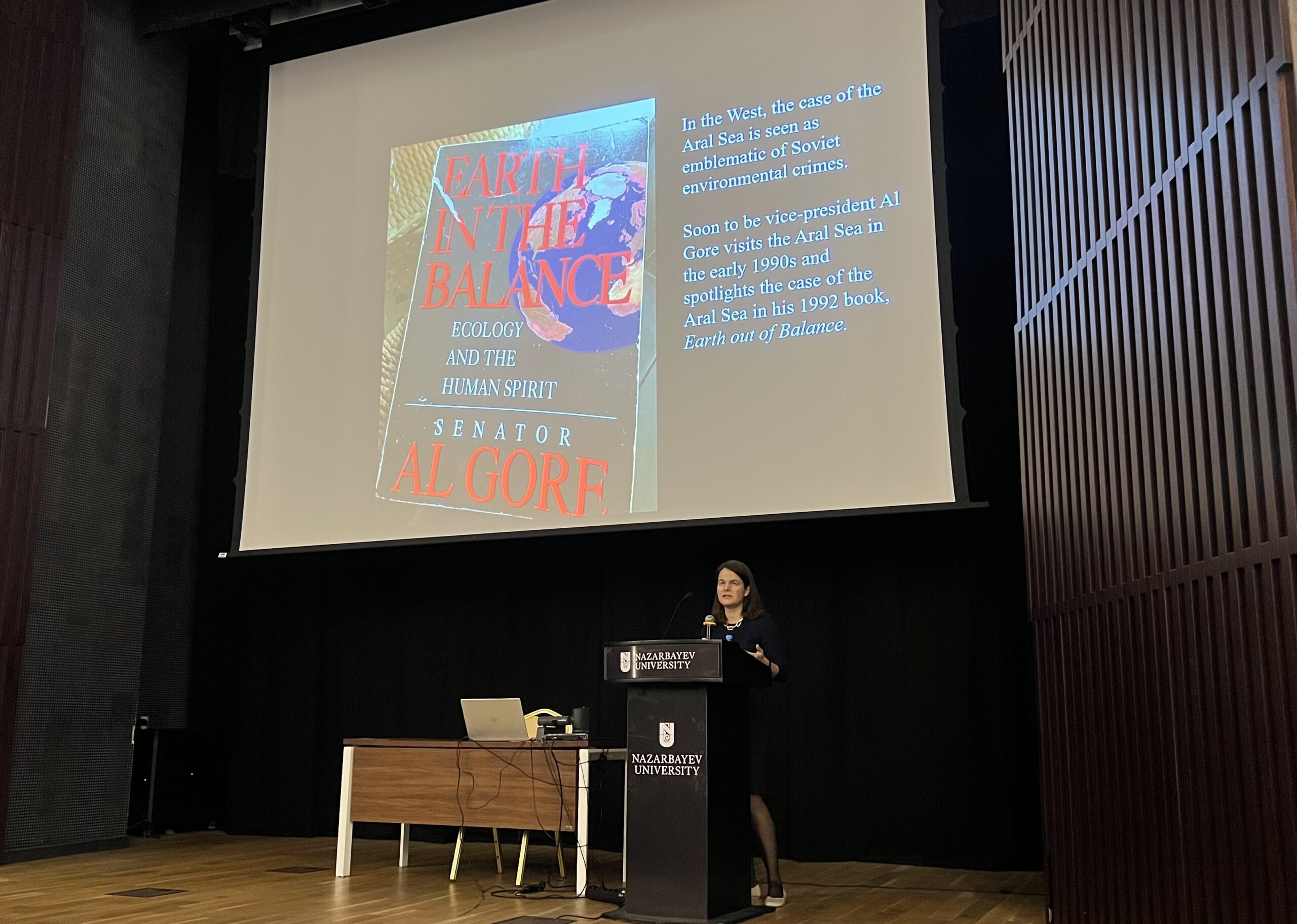

Cameron explained that the Aral Sea has been portrayed in strikingly different ways depending on the political context. In the West, it became a symbol of Soviet environmental destruction.

“If you look at the literature in the West, the loss of the sea really becomes this very kind of paradigmatic Soviet environmental crime,” she said.

Al Gore’s 1992 book “Earth in the Balance” cited the Aral Sea as a symbol of Soviet environmental destruction. Stranded vessels on desert sands became its enduring image. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

She noted that former U.S. Vice President Al Gore featured the Aral Sea in his 1992 book, “Earth in the Balance,” as an example of the Soviet Union’s destructive relationship with nature. Images of stranded fishing vessels on desert sands became emblematic of the Aral Sea’s fate.

Within the Soviet Union, however, the retreat of the sea was often framed as a success of modernization, as the region became the world’s second-largest cotton producer.

According to Cameron, the three countries bordering the Aral Sea take divergent approaches. Kazakhstan designates it a legal disaster zone, entitling residents to higher state pay and social support. Uzbekistan promotes the area as a hub of innovation and technology, while Turkmenistan rarely acknowledges the disaster.

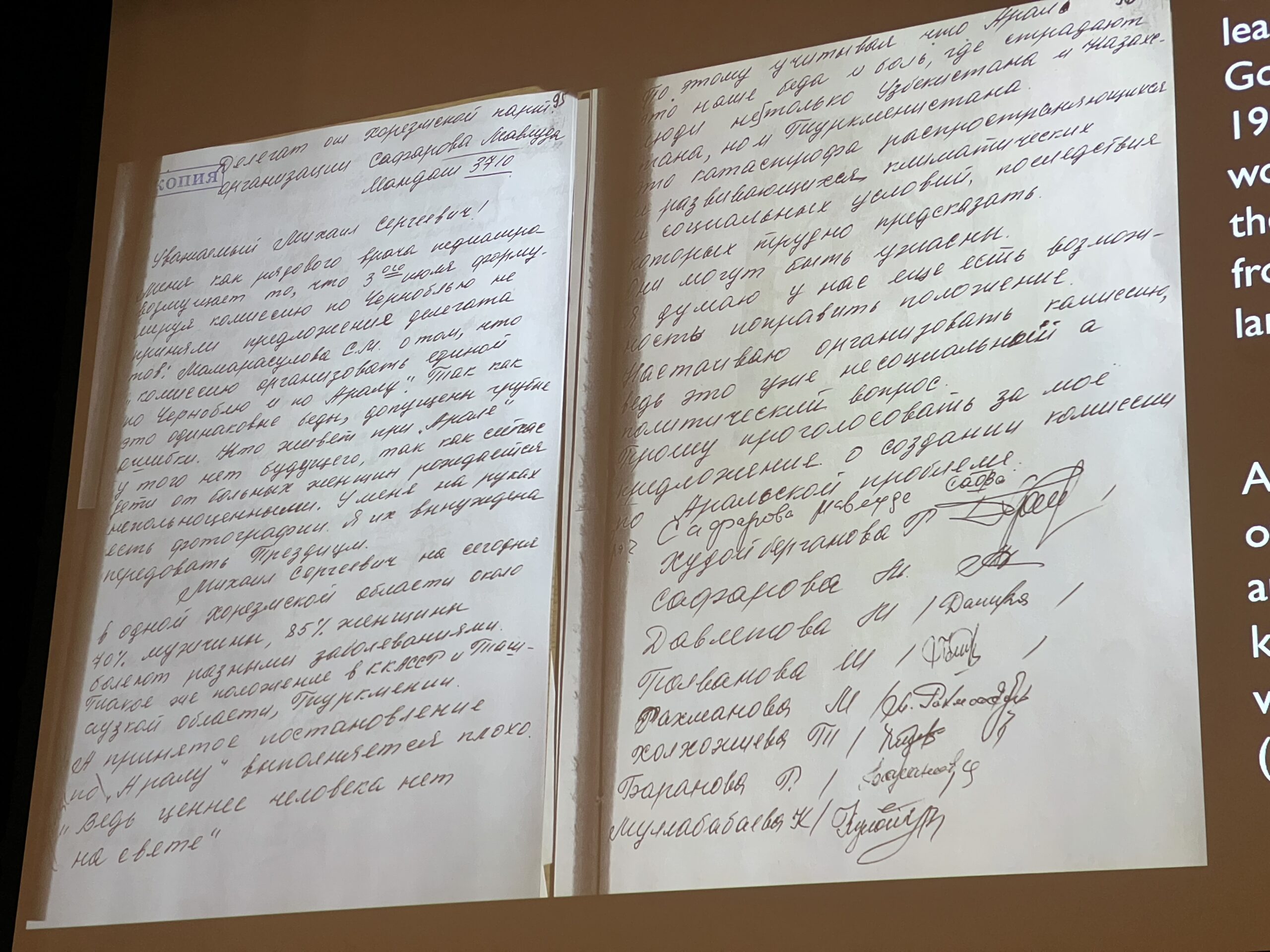

Presentation by Dr. Sarah Cameron at Nazarbayev University. Letter to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, late 1980s, from nine women, most of them pediatricians from the Aral Sea leands. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

Despite these narratives, Cameron emphasized that what unites them is the absence of those most affected.

“One thing I would note in all of these versions of the story are the profound effects of the crisis on the people who lived around the sea. By this I mean economic dislocation, cultural destruction, and devastating impact on human health. They’ve largely been ignored,” she said.

“The Aral Sea and the Aral Sea disaster, I would argue, has been represented and envisaged largely as an environmental crisis, not as a human one. And I would argue, actually, this is in many ways representative of how climate change is portrayed more generally,” she said.

Cameron’s forthcoming book seeks to move beyond that framing by tracing the marginalization of the region’s people across the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and the post-Soviet states.

Voices from the Aral Sea

“Speaking with people has really helped me correct the mistaken impression that the sea’s demise is purely an environmental crisis rather than a human one,” she said.

She noted that as the Aral Sea receded, food security collapsed. Livestock died, crops withered and produce became scarce, leaving communities without reliable nutrition. The once-thriving fishing industry disappeared, erasing livelihoods and local identity. Hospitals were soon overwhelmed, and many villages remained isolated due to poor roads and infrastructure.

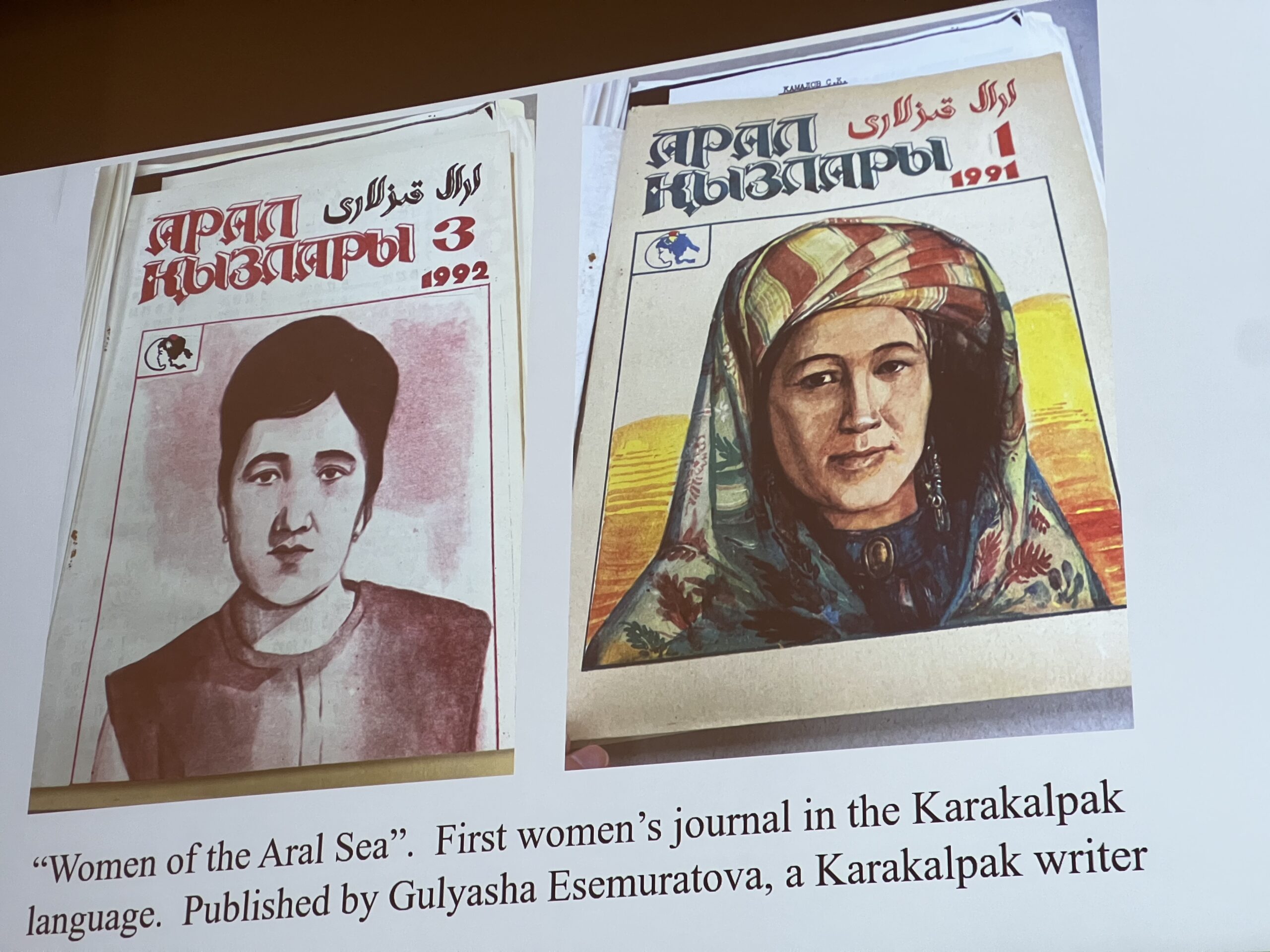

Dr. Sarah Cameron presents the story of Gulaysha Esemuratova, a Karakalpak writer, who founded the journal “Women of the Aral Sea” to document the suffering of her community. Photo credit: Nagima Abuova / The Astana Times

Cameron also highlighted the persistence of voices from the region, particularly women. Roza Baglanova, the renowned Kazakh soprano, denounced public health problems before the Soviet Central Committee. Gulaysha Esemuratova, a Karakalpak writer, founded the journal “Women of the Aral Sea” to document the suffering of her community.

“But a lot of what they had to say has attracted surprisingly little attention, both from the region’s post-Soviet successor states and from the international community,” said Cameron.

Lessons for the future

The Aral Sea’s decline, Cameron noted, is a cautionary tale for other fragile ecosystems, such as the Great Salt Lake in the U.S.

“Salt lakes in general are pretty fragile. They’re very reactive to any type of disturbance. It’s not a coincidence that, in fact, we actually see a number of salt lakes around the world under threat. We might think of these lakes as the canaries in the coal mine,” said Cameron.

“They warn us in advance of environmental shifts, often before we see them elsewhere,” she added.