The European economy is stuck in what is best characterized as perennial economic stagnation. There’s no end in sight to it, which makes it easy to understand commentators who propose quick-fix reforms instead of addressing the root causes of Europe’s deeply entrenched structural economic problems.

One such example is the five-point list presented recently by Shanker Singham of the British Growth Commission. Highlighting the need for cheaper energy, an integrated risk-capital market, and more permissive economic regulations, Singham—correctly—suggests that we all gain from expanding the freedom of entrepreneurs, investors, and markets.

Unfortunately, this focus on the private sector is a classic example of ignoring the elephant in the room. We can give entrepreneurs and investors all the professional freedom they want—if Europe does not reform away its large, intrusive welfare state, the reforms on Singham’s list will fizzle out before they make any meaningful difference.

On the other hand, if placed in their proper context, his reform ideas can indeed help reignite the European economy.

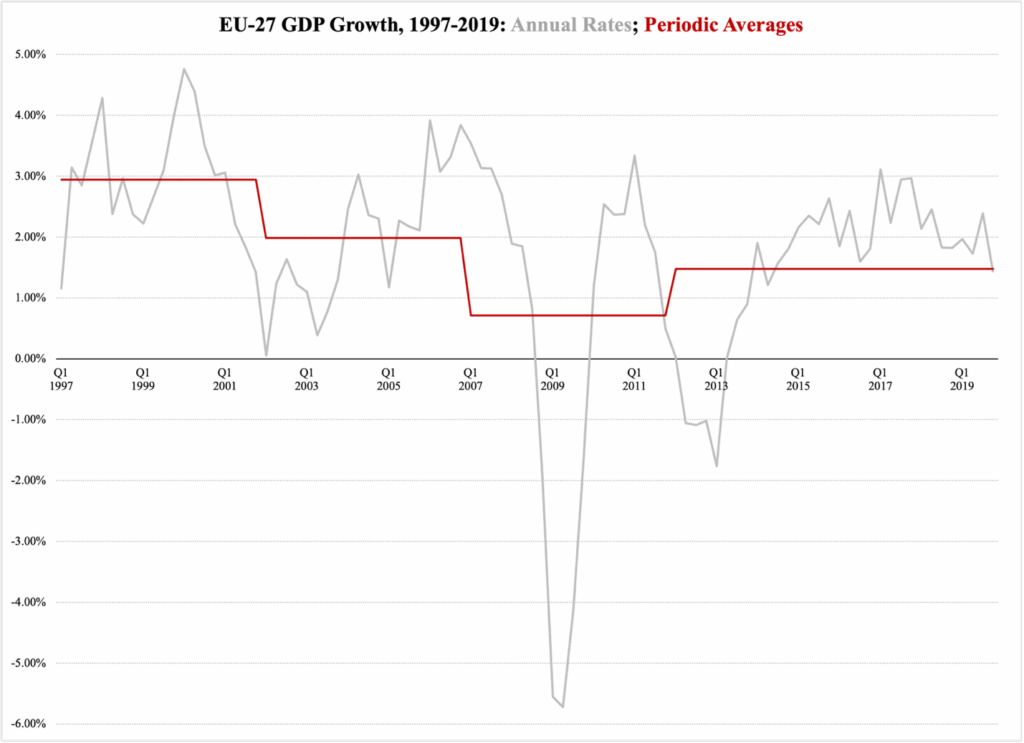

Before I lay out the parameters of structural welfare-state reform, let me first agree with Singham on the point that Europe has a deeply rooted problem with low economic growth. Although economic growth began slowing down in many countries in the 1990s—and in some cases a decade earlier—the most troubling decline has happened in the past 20 years. Figure 1 reports the real, average GDP growth rate for the current 27 EU member states for the period 1997-2019.

Figure 1

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Source of raw data: Eurostat

The average annual growth rate for the five years 1997-2001 was 2.9%. For 2002-2006 it fell to 2%, though it is worth noting a brief top just a hair short of 4%. When the Great Recession hit, there was an equally brief encounter with negative growth; for the entire period 2007-2011, the European economy only grew by 0.7% per year, on average.

By 2011, Europe was deep into the ‘integration’ process known as the European Union—which de facto turned out to be a superstate project more than anything else. But the continent had also created a very troubling habit of:

a) steadily growing its welfare state, and

b) raising taxes to pay for it.

The welfare state is a potent growth suppressant. When government monopolizes a service, e.g., health care, by definition, it ends the free market’s pursuit of efficient resource utilization in that sector. The monopoly replaces ‘do more’ with, at best, ‘do more with more.’ Often, the outcome is ‘do less with more’—either way, the government monopoly stops the health sector from contributing to the nation’s GDP. This happens in part through the sector monopolized by government, in part on adjacent markets.

When GDP growth slows down permanently—as in Figure 1—tax revenue becomes a permanently inadequate source of government funding. This is why, during the first three periods in Figure 1, the current 27 EU member states gradually drift into a fiscal shadow realm of permanent budget deficits.

When governments become permanent borrowers, they suck up significant amounts of risk capital. Faced with an increasingly stagnant and unprofitable private sector alongside a virtually endless supply of sovereign debt, intelligent investors reallocate some of their portfolios to virtually risk-free treasury securities.

The more widespread the budget deficits are, the more government crowds out the private sector and steals its risk-capital thunder.

Even as the EU-27 economy recovered after the 2008-2010 Great Recession, it never reached its previous levels of glory: 1.5% for the whole period 2012-2019 and 2.2% for the strongest segment, 2015-2019.

Nothing has changed since then, at least not for the better. Even after the 2020-2021 pandemic, Europe has been unable to reap any meaningful economic harvests. From the first quarter of 2024 through the second quarter of this year, the EU GDP has grown by only 1.1% per year, on average.

To break out of what has de facto become a state of perennial economic stagnation, the EU member states must put any proposals for private-sector reform on the back burner. No matter how good those proposals are in terms of encouraging entrepreneurship and capital formation, the resources unleashed accordingly will eventually succumb to the formidably stagnant forces of the welfare state.

Therefore, Europe must begin its pursuit of a brighter, more prosperous future by structurally reforming away its current, economically redistributive welfare state. That reform process comes in three steps, the first of which is to untie social benefits from household income.

The most problematic type of benefits in Europe’s current welfare states is one where households qualify for help because of the relative size of their income; the less they make compared to, e.g., median household income, the more benefits they get. This directly disincentivizes workforce participation, both in its entirety—discouraging people from even entering the workforce—and in part.

Benefits that taper off as household income rises create hidden, and often significant, effective marginal taxes on household income. The labor force participation required to make it ‘worth the while’ to lose those benefits is often socially and economically unattainable for many people.

Instead of benefits that are negatively tied to household income, we must replace them with one of two benefits models:

The Beveridge model, where benefits are basic but dignified and only available to those who have no other means to support themselves; or

The Hungarian model, where benefits are paid out to families for purposes unrelated to their relative economic situation.

The Hungarian model is a welfare state built on conservative principles. It is designed to promote the formation, growth, and prosperity of nuclear families. It preserves benefits, but not of such an architecture that they disincentivize workforce participation. This model is highly recommendable, but since I have written aplenty on it in the past, let me outline here the full picture of the more radical reform alternative.

Step two begins when step one has gone into effect. Once we have reformed the welfare state so that its benefits system no longer discourages productive economic activity, our next step is to dismantle government monopolies in service sectors. The most pressing example is health care, where the introduction of competition between private insurance plans (as in the Dutch reform from 20 years ago) replaces the tax-funded single-payer model that currently dominates Europe’s health care systems.

With private insurance plans competing with each other, we also deregulate the health care market itself. This will gradually bring about an end to government monopolies on hospitals, health care clinics, employment for medical professionals, and other statist criteria applied around Europe.

Education is a similar service monopoly in government hands. There are others, such as income security savings through tax-funded, government-regulated social insurance schemes. For every one of these service industries that is deregulated and entrusted to the private sector, the forces of competition and economic growth within those markets will meaningfully contribute to an economy-wide boost in economic activity.

With the reform to social benefits and the privatization of government service monopolies complete, it is time for the next step, namely a structural reduction of taxes. A substantially smaller government can get by on substantially lower taxes; a major tax reform that lifts a significant portion of the current tax burden off households and businesses will have strongly positive effects on economic activity across the economy.

Once these three reform steps have been implemented, we can turn our attention to the more specific regulatory issues brought up in Singham’s article. Taken together, all these reforms have the potential of bringing Europe’s economy up to 4% or more in annual economic growth.

Does Europe have the political leadership and legislative courage to embark on this kind of economic reform journey? Let us hope that the answer is yes.