ANKARA — At the Republic Museum in Ankara, 83 Roman coins gleamed under the lights at a handover ceremony on Sept. 29. Minted in Anatolia during the third- and fourth-century reigns of the Roman emperors Maximianus, Constantine I, Constantine II, and Arcadius, the coins had been seized in 2015 in the United States, and after a decade, were returned to Turkey under a 2021 bilateral agreement to protect cultural heritage.

Deputy Culture and Tourism Minister Gokhan Yazgi received the artifacts from Brian Stimmler, charge d’affaires ad interim at the US Embassy. “The process was swift, transparent and efficient,” said Yazgi, calling the coins “reflections of the Roman Empire’s political and military life.” The ceremony added to a tally that Ankara now presents as proof of its global cultural diplomacy.

Culture and Tourism Minister Mehmet Nuri Ersoy, speaking to media representatives in Manisa earlier this year, said that more than 13,000 artifacts have been repatriated to Turkey since 2002, including 1,149 in 2024.

He attributed the progress in recovering artifacts to a changed policy at the ministry. “We have made serious progress by strengthening protocol mechanisms and raising the institutional level of the department in charge,” Ersoy said.

The coins repatriated from the United States were minted in Anatolia during the reigns of emperors of the Late Roman Empire. (Photo: Ministry of Culture, 2025)

The Anti-Smuggling Department has been elevated to a full directorate, and its head, Zeynep Boz, has become a familiar public figure, often speaking to domestic and international media whenever a high-profile antiquity is recovered and returned to Turkey. Her ministry also maintains a continually updated public register of repatriated artifacts on its website, listing the origin of each object and the return process.

Ersoy said the ministry’s goal is not only to bring back artifacts already abroad but to also prevent new losses. Teams have worked with village leaders and schools to raise awareness, discouraging locals from selling items they find. He also highlighted the ministry’s activities as acting as a deterrent for buyers, saying, “If you exhibit or auction an artifact taken out illegally, we will detect it and initiate the legal process to get it back. Knowing this is what really deters them.”

Ministry officials keeping an eye on auction catalogues has paid off. Earlier this year, a British auction house withdrew an Iznik tile looted from the 16th-century Seyhan Ulu Mosque, in Adana, after Turkish government intervention. The dealer admitted to holding a second tile, which was also returned, and a private collector turned over a third piece to the London police. The trio of tiles, with their bold palette of coral red, cobalt blue and turquoise, came home in 2025.

İznik tiles returned from the UK (Photo: Ministry of Culture, 2025)

In another case, Turkey reclaimed a rare manuscript of the Quran copied by Mustafa Dede, son of the famed Ottoman calligrapher Sheikh Hamdullah, that had surfaced in 2017 at Christie’s in London. After lengthy proceedings, the 16th-century Quran was repatriated in 2024 and placed in the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istanbul.

Mistakes of the past

For much of the 19th century, Ottoman laws permitted foreign excavators to retain a portion of their finds, and oftentimes antiquities left the empire as diplomatic gifts. Only in 1884, under the reforms of Osman Hamdi Bey, director of the Imperial Museum, did the state ban the export of antiquities by declaring all of them national property.

Today, Turkey relies on bilateral agreements, close coordination with prosecutors and customs officials abroad, and the persistence of its own archaeologists in identifying Turkish antiquities held abroad. In addition, officials scan auction catalogs and museum holdings worldwide.

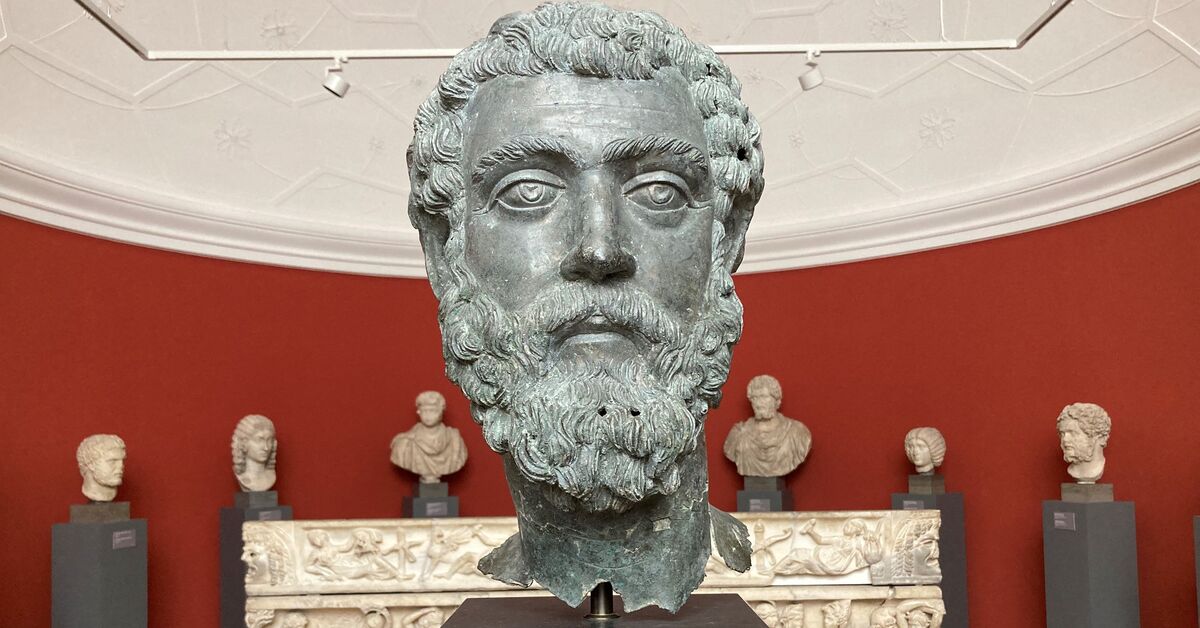

The number of recovered antiquities and artifacts is climbing. In Antalya this spring, Denmark’s Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek returned the bronze head of Septimius Severus and 48 terracotta plaques looted in the 1960s. Both the museum authorities and the Danish ambassador, Ole Toft, stressed that Copenhagen had acted “on ethical grounds” after the artifacts’ origins were verified.

In Bern, Switzerland, seven antiquities were handed back, ranging from Bronze Age gold figurines to Roman glass. Yet thousands more remain abroad. The British Museum alone lists nearly 74,000 Anatolian objects in its collection, while Ankara continues to press for marquee returns, such as the Pergamon Altar in Berlin.

Cooperation with the US

The United States stands at the center of several high-profile repatriations. The return of two bronze statues from the ancient site of Bubon — one of Emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161–169) in October 2022 and what is widely believed to be (a headless) Marcus Aurelius in 2025 — were both celebrated wins.

The return of Lucius Verus, after decades in the collection of the American philanthropist Shelby White collection, a treasure trove long criticized by archaeologists for housing looted material, followed years of lobbying by Turkish officials, archival research and testimony compiled by the late archaeologist Jale Inan and the journalist Ozgen Acar.

“The return of Lucius Verus is one of the greatest victories of the Turkish repatriation efforts,” Acar told Al-Monitor in one of his last interviews before he died in 2024. “Bronzes from that era, the mid-second century CE, were often melted down, so very few remain in the world, let alone in Turkey.”

In a second coup, the Cleveland Museum of Art agreed in February 2025 to surrender a headless bronze statue long displayed as “Draped Male Figure,” but believed to depict Marcus Aurelius, after a Manhattan district attorney investigation tied to Bubon, in Burdur.

The Marcus Aurelius statue’s return was celebrated in August 2025, when it went on public display for the first time at the Presidential Complex in Ankara, presented as the centerpiece of the exhibition and symposium “Golden Age of Archaeology,” opened by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. In a speech on the occasion, Erdogan said archaeology “is not only about uncovering artifacts, but about claiming our place in the history of civilization.”

Marcus Aurelius displayed at the Presidential Complex (Photo: Ministry of Culture, 2025)

Erdogan tied archaeology directly to national identity, saying, “As a nation, we have been here for a thousand years. We live on these lands, and God willing, we will continue to remain here until doomsday.” He presented archaeology as central to the government’s vision of the “Century of Turkey,” part of a strategic approach using repatriation victories to project cultural authority abroad, an arena in which Turkey currently leads. This is taking place as critics note that contemporary art deemed provocative has been sidelined and brutally attacked under AKP cultural policies.

Safeguarding heritage at home

While Ankara celebrates its triumphs abroad, opposition figures argue that Turkey’s remaining cultural heritage at home is often mismanaged or threatened by short-term political and commercial interests.

Gulsah Deniz Atalar, CHP deputy chair for culture and tourism, has raised objections on two recent fronts. In a written statement to the media on Oct. 1, she criticized restoration planning for the dome of the great Ottoman architect Sinan’s Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, saying, “Selimiye, which [Sinan considered his masterpiece] is no one’s sketchbook. The court has issued a stay of execution, and we will continue to monitor the case to see that the restoration is faithful.”

In Antalya, Atalar has led the fight against the planned demolition of the Antalya Archaeological Museum, home to more than 14,000 artifacts, including the statues of Lucius Verus and Septimus Severus, on the grounds of earthquake risks. She calls the project “the plan of the concrete lobby,” warning that it will erase not just a world-class collection’s setting but also a landmark of modern Republican architecture.

“The Antalya Archaeological Museum is itself a manifesto of the Republic’s faith in culture,” Atalar said. “To bulldoze it under the guise of earthquake safety, rather than strengthen the building, is cultural vandalism.”

Atalar’s warnings about the Antalya Museum have now been presented before the courts after an Antalya resident filed a lawsuit against the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in July. Despite opposition from the CHP and local architecture associations, independent outlets reported in August that bulldozers had already begun to work on parts of the complex, a move that sharpened criticism of the ministry and raised fears for one of Turkey’s most important archaeological institutions.