(AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Bottom Line Up Front

United Nations sanctions on Iran, suspended in 2015 to implement the multilateral Iran nuclear agreement (JCPOA), were reimposed Saturday night by the European parties to the JCPOA under a “snapback” mechanism built into the deal.

The sanctions snapback will impede Iran’s ability to overcome a series of severe setbacks to its geostrategic architecture.

Russia and China tried to block the sanctions, the snapback, and will mostly ignore the re-imposed regulations, helping Tehran mitigate the economic and strategic repercussions.

Iranian leaders have calibrated their retaliation to the sanctions snapback, signaling they welcome renewed nuclear diplomacy.

On Saturday, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced, on behalf of President Trump, that: “This evening, at 8:00 p.m. EDT, the United Nations reimposed sanctions and other restrictions pursuant to six UN Security Council Resolutions — 1696, 1737, 1747, 1803, 1835, and 1929 — based on Iran’s continuing ‘significant non-performance’ of its nuclear commitments. Their reactivation concludes the snapback process initiated on August 28, 2025, in an act of decisive global leadership on the part of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.” U.S. leaders attributed the European action to Tehran’s violation of its commitments under the 2015 multilateral Iran nuclear agreement (JCPOA) — particularly its enrichment of uranium to 60 percent purity (only 3.5 percent purity was permitted by the JCPOA) and accumulating a stockpile of 400 kilograms of highly enriched uranium. That stockpile is enough, if enriched to 90 percent purity (weapons grade), for nine nuclear weapons, according to nuclear proliferation experts. Iran was also accused of barring the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) from continuing its on-site monitoring of Iran’s nuclear facilities, following the June Israeli and U.S. airstrikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities.

UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which endorsed the JCPOA, allows any party to reinstate UN sanctions if Tehran fails to uphold its JCPOA commitments. The snapback mechanism is structured to prevent any permanent Security Council member from using its veto to prevent the mechanism from being triggered. The United States was unable to trigger the snapback mechanism itself because, in 2018, during his first term, President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the JCPOA and therefore lacked standing to activate the snapback mechanism.

The reimposition of UN sanctions is sure to worsen Iran’s already dire economic conditions, including significant shortages of water and electricity, 40 percent inflation, and a precipitous decline in the value of Iran’s currency, the rial. The revived UN sanctions on Iran’s weapons and strategic technology sectors are sure to impede Iran from reversing the severe strategic setbacks Tehran has suffered over the past year, as a result of Israel and U.S. attacks that have damaged Iran’s nuclear facilities and weakened its regional allies. The snapback reimposes a restriction — which had expired in 2023 — on Iran’s development and use of ballistic missile technology. Iranian leaders identify their large arsenal of ballistic missiles as the country’s main strategic deterrent. In addition, the snapback reimposes an embargo on all conventional weapons transactions with Iran, a prohibition that had expired in 2020.

The renewal of the restriction might complicate Tehran’s effort to replace or repair the air defense systems severely damaged by Israeli air strikes, or to acquire the latest-generation combat aircraft Tehran lacks. The weapons transactions embargo is also intended to hinder Iran’s ability to arm its Axis of Resistance partners around the region; however, Iran routinely violated that provision in the years it was in force. The UN action furthermore restores authority for UN member states to seize weapons and other prohibited cargo being transferred by Iran to state and non-state actors. Also, Iran will again be banned from enriching uranium, processing heavy water, or undertaking other nuclear activities that were otherwise permitted under the JCPOA.

The sanctions snapback took effect despite efforts by Iran’s key strategic partners, Russia and China, to thwart the process. On Friday, the two powers sponsored a last-ditch resolution in the Security Council that would have delayed the snapback for six months. However, the draft did not receive the nine votes required for approval. Russia and China sought a six-month delay to provide more time for Iran to meet the conditions stipulated by the UK, France, and Germany (“E3”), allowing the snapback mechanism to expire outright in October. The E3 demanded that Iran: provide immediate access for the IAEA to Iran’s nuclear sites; provide information on the location and status of Iran’s 400-kilogram stockpile of highly enriched uranium; and open direct nuclear negotiations with the United States. In an effort to satisfy the E3’s conditions, Iran had agreed to resume some cooperation with the IAEA, and its negotiators reportedly informally exchanged proposals on a new nuclear accord with Trump officials. However, the E3, in consultation with Washington, judged Iran’s actions and offers as insufficient to warrant dropping or delaying the snapback of sanctions.

After failing to derail the sanctions snapback, Russia and China are likely to help Tehran mitigate the effects of the reimposed sanctions. Both powers have already stated that they do not consider the snapback measure legitimate and will continue to trade with Iran at the existing levels. Russia and Iran have established a formal strategic partnership, under which Iran sells Moscow the sophisticated armed drones it uses in the war in Ukraine. Iran’s drone supplies to Russia are expected to continue even though the sales would constitute a violation of the reinstated UN sanctions. Russia might also resupply Tehran with sophisticated air defense systems, such as the S-300 or S-400, which were rendered inoperable by Israel’s June air offensive against Iran. Moscow would likely argue the systems are purely defensive and intended to deter further Israeli attacks on Iran. The snap back might, however, cause Russia to think twice about delivering Iran the sophisticated Su-35 combat aircraft Tehran has sought to order.

For its part, China is likely to help Iran — and itself — by continuing to purchase large volumes of Iranian oil. Chinese refiners, some of which have been sanctioned by the U.S. government, have been purchasing more than 1.5 million barrels per day for at least the past year. The oil sales are crucial to efforts by Iran’s government to forestall all-out economic collapse. The trade also benefits China, as Iran discounts the price of oil to encourage the transactions. Experts assess that the sanctions snapback is likely to prompt Tehran to increase that discount to 20 percent. Beijing has stated that it will continue to buy oil from Iran, even if the sanctions snapback were to take effect — apparently calculating that U.S.-China relations are so complex that the Trump team will be deterred from punishing China over the Tehran oil trade.

Yet, all sides are seeking space for diplomacy that could yield a new multilateral nuclear agreement and, ultimately, provide Iran with substantial sanctions relief. In his statement announcing the snapback had entered into force, Secretary Rubio stated: “President Trump has been clear that diplomacy is still an option — a deal remains the best outcome for the Iranian people and the world. For that to happen, Iran must accept direct talks, held in good faith, without stalling or obfuscation.” A pact would offer Tehran not only the rollback of the UN sanctions that have been reinstated but also relief from the U.S. architecture of secondary sanctions. By all accounts, U.S. sanctions, which force global firms to choose between doing business with Iran or engaging in the exponentially larger U.S. economy, damage Iran’s economy to a far greater extent than will the reimposed UN sanctions. For the U.S. and its partners, a nuclear agreement with Tehran would ensure Iran could not develop an actual nuclear weapon, reduce the potential for U.S.-Iran or Israel-Iran escalation, and possibly pave the way for cooperation with Iran on a broad range of regional issues.

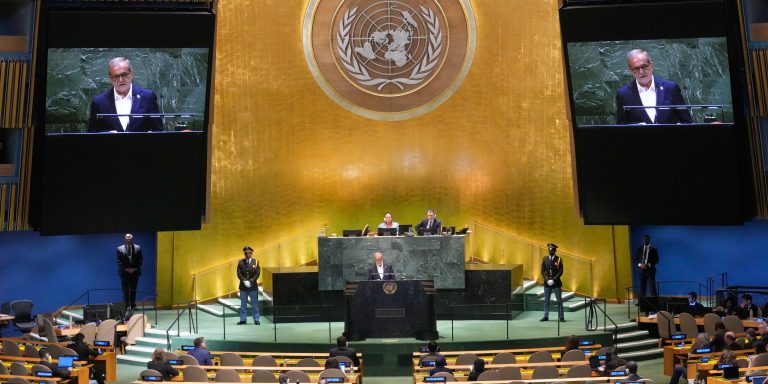

Iranian leaders are suggesting they want a negotiated settlement of the nuclear and sanctions disputes, although not at any price. On Friday, on the eve of the snapback taking effect, and while in New York for the UN General Assembly meetings, Iran’s President, Masoud Pezeshkian, called the snapback invocation “unjust and illegal. They [U.S. and Europe] want to topple us … If you were in our place, what would you do?” He told journalists Iran would decide on retaliatory steps after he returned to Iran and conferred with other officials. Yet, Tehran’s actions have been modest. On Saturday, Iran’s foreign ministry recalled its ambassadors to each of the E3 countries for consultations. Pezeshkian and other moderate leaders appear to have prevailed against hardline factions arguing for a much more forceful retaliation, including an Iranian withdrawal from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Moderates argue such a decision would raise alarm among Trump officials and European leaders and close off avenues for new nuclear talks with the Trump team. In interviews with U.S. news outlets during his trip to New York last week, Pezeshkian dismissed consideration of an NPT pullout, saying it was “not an option.” Still, top Iranian leaders continue to insist that Trump’s demand that any new agreement forbid Iran from enriching uranium is non-negotiable, a stance fueling significant global pessimism that a new U.S.-Iran nuclear agreement can be reached.