I was invited on to BBC’s Red Lines podcast recently to talk about the possibility of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout for the UK. My initial reaction was ‘has someone actually suggested that?’ so sure was I that it was a joke. Once I’d done some digging, it turns out serious people have floated it.

It is an idea that baffles me. Talk of an IMF bailout is fantasy. Britain today borrows in its own currency, has an independent central bank and doesn’t need dollar loans.

I can’t fathom a scenario where the IMF rides into the rescue. Seeing how it went in 1976, what government would crash their credibility in such spectacular fashion when there’s absolutely no need to do so.

But UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ upcoming Budget is no joke. Having already set up stringent spending rules, raised many billions in extra tax revenues, and overseen a spending review that barely turned the spending taps on, she is facing into a budget where she is likely going to raise taxes again.

On Red Lines, I wondered if the IMF suggestion is borne of a desperation for attention or a political attempt to reignite the deep British psychological embarrassment of the 1976 IMF bailout.

While I’m cynical of the motives, raising the IMF bailout idea does reveal a truth: Reeves’ room for manoeuvre is desperately limited. If she mishandles the Budget, she’ll get more spikes in gilt yields and a surge of headlines about “Truss 2.0”.

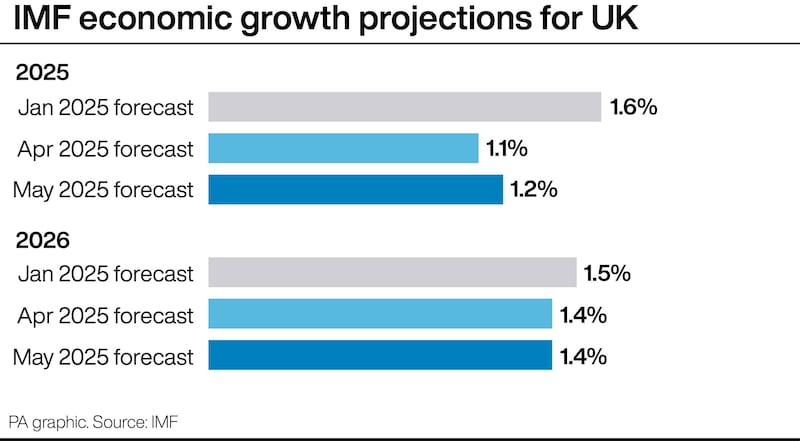

Current IMF growth projections for the UK (PA Graphics/Press Association Images)

Current IMF growth projections for the UK (PA Graphics/Press Association Images)

If Liz Truss’s time taught us anything, it is that credibility can disappear in one trip to the dispatch box and never return.

The numbers driving this Budget are relentless. Tax thresholds frozen for years mean fiscal drag is doing some of the heavy lifting but at political cost. Big-ticket spending plans are being trimmed or delayed.

Even so, the underlying arithmetic doesn’t add up to anything like a transformative programme.

The Labour government has spent a lot of political capital blaming the last government while also promising stability and renewal. It promised to unleash planning reform and green investment.

It has promised better public services without “tax and spend” shocks. It is fair to say that the early promises haven’t been delivered on.

In Northern Ireland, we are living through the consequences of a lack of funding. At an event I attended recently, the depth of Stormont’s budget crisis was spelt out starkly.

Pay disputes rumble on without settlement funding. “Transformation” money exists mostly on paper. In some areas we’re already living in the post-Budget world that Reeves is trying to avoid – short-term fixes, exhausted fiscal goodwill and diminishing credibility.

That’s why the IMF talk really irritates me – because it’s not just wrong, it’s ridiculous. Britain is not 1976. Reeves isn’t staring at an IMF rescue; she’s staring at hard domestic choices.

And so is Northern Ireland. We cannot realistically think that London will keep sending “one-off” cheques, not without something in return.

As hard as it might look for the Chancellor, she, and we, are not condemned to endless salami-slicing and Income tax/national insurance raids. There are genuine policy choices on the table if Reeves wants to grasp them.

A modest wealth tax could broaden the tax base without hammering wage earners.

Ending the practice of paying commercial banks interest on their vast reserves at the Bank of England – an idea that has moved from fringe blogs into serious policy papers – could release billions a year for public spending or debt reduction.

These measures would provoke fierce debate, but they show the constraints are political as much as fiscal.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves could be left at risk of breaking her fiscal rules by unexpected economic shocks and faces “significant challenges” in delivering the Government’s agenda, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned (Jacob King/PA)

Chancellor Rachel Reeves could be left at risk of breaking her fiscal rules by unexpected economic shocks and faces “significant challenges” in delivering the Government’s agenda, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned (Jacob King/PA)

This Budget will therefore be about signalling as much as spending. Reeves can play it safe and keep slicing, or she can start sketching a new fiscal architecture.

Either way, she has to show markets and voters she understands the constraints and has a believable plan through them. That means being honest about tax, clear about priorities and transparent about what will be cut, delayed or re-phased.

Markets are unlikely to demand IMF-style austerity, but they will punish anything that looks like denial. As the Truss-Kwarteng episode showed, Britain can still be brought to heel by its own investors.

And, as the NI Executive is learning, you can’t transform public services with transformation funding alone if the core budget is unsustainable.

The IMF bailout may haunt British politics forever, but that feels like a distraction from the real issues.

As the Chancellor puts the finishing touches to her autumn Budget, and as Stormont officials seek to solve an impossible financial conundrum, the question isn’t ‘Will the IMF intervene?’ but ‘Will we choose a different fiscal path?’.

Andrew Webb is chief economist at Grant Thornton NI