The word war itself evokes horrific images and sentiments. Yet war through the eyes of children feels almost unimaginable — among the most grotesque moral failings of humanity.

War heightens awareness of tragedy, and while many make the mistake of considering children naïve, they perceive its horrors with sobering clarity, forced to mature faster than time can keep up with.

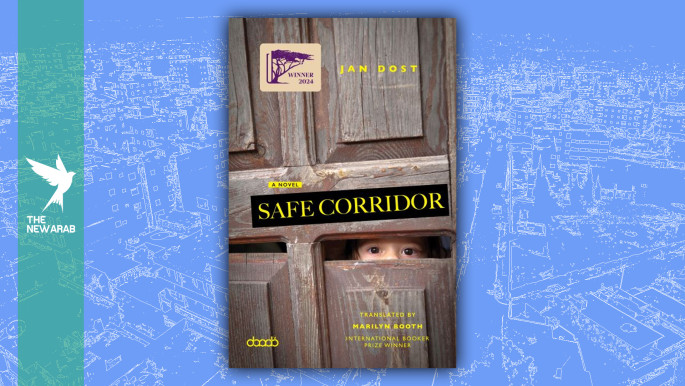

Syrian-Kurdish author Jan Dost captures this impact on the youngest victims of war in his novel Safe Corridor.

Centred on the hope for safe passage through the chaos of war, Dost’s first novel to be translated into English, unfolds through the perspective of a 13-year-old Kurdish boy, Kamiran.

In this Kafkaesque tale, Kamiran’s family faces continuous displacement during the violent occupation of Afrin by Turkish forces in 2019.

Like his contemporaries Samar Yazbek, Dima Wannous, and Khaled Khalifa, Jan joins a generation of Syrian writers who have documented the unending unrest throughout Syrian and Kurdish history.

Yet Kamiran’s story stands apart, not only for its perspective but also for its unfiltered, indignant language.

Delving into the depths of Kamiran’s mind, Dost exposes the boy’s trauma — the violations on both his body and mind. These psychological and physical wounds are profoundly uncomfortable for the reader.

Dost also succeeds in capturing the crude yet authentic thoughts of a pre-teen forced to grow up in merciless circumstances.

Kamiran’s narration is neither lyrical nor hopeful; it is raw and painfully honest. His surreal transformation into a piece of chalk, and the terror that accompanies it, is a visceral experience.

The attack on Afrin

Set in early 2019, the story unfolds as the Turkish army and allied militias attack Syria’s Afrin region, forcing its mainly Kurdish inhabitants to flee.

The novel opens with Kamiran in his family’s tent in a refugee camp, where he describes himself morphing into a pale piece of chalk.

He then takes readers back to the beginning of his family’s troubles, when he felt an overwhelming urge to write something — but had nothing to write with. Instead, he opened his heart to a piece of yellow chalk that became his companion.

With macabre humour, Kamiran narrates his family’s hardships and grief.

He recalls his missing father’s words matter-of-factly: “All revolutions are alike, Kamiran, my boy. They’re just like a** droppings — you can’t tell one from another. Or like hair — everyone likes it there. Baara Shaara!”

The story introduces his mother, Layla, once a vibrant professor before the war; his father, a surgeon; his younger brother, Alan; and his toddler sister, Maysoon.

After Daesh (Islamic State) kidnaps his father from their village of Manbij, the family flees to Aleppo and later Afrin, only to discover that safety is an illusion.

In Aleppo, Maysoon is killed by a bomb, a loss that proves too much for her mother, Layla, who becomes mute — a phantom spirit among the living.

Although his mother is still present, Kamiran feels like an orphan, forced to face the dangers of war on his own. Her silence and the chaos around them prevent him from attending school, leaving him at the mercy of adults and the horrors he witnesses, which cause him to wet the bed at night.

Through these migrations and displacements, Kamiran tells his story, where his family is eventually led to believe that the Turkish occupying forces have opened a so-called safe corridor for refugees.

Writing from a child’s perspective is no easy task. Dost conveys the innocent anger of a boy robbed of his childhood, his mimicry of adult vulgarity, and his sharp observations of a world collapsing around him.

Kamiran confides in his chalk: “Do you know, my pale friend, do you know the hurt that the families of the kidnapped and disappeared have to bear? Just ask me. It’s a hurt like no other. Maybe it feels something like a knife that’s been rammed into the heart and is waiting for someone to come along and pull it out. Or to treat the wound. Or to announce another death?”

A shattered childhood

Kamiran’s suffering is relentless. His grief and humiliation, his cursing and bedwetting, are all reactions to the unimaginable.

He views his own struggles as inconsequential and embarrassing compared to the total upheaval of his family’s life, so he keeps them to himself.

In war, the adults who should guide children are too busy surviving and dealing with their own pain to offer help.

Even his grandfather tells him he will understand what war really is when he grows older, but Kamiran quietly reminds readers: “My grandfather didn’t realise that we children are the people who best understand what war means. It’s we children who know wars as they really are, not the adults… I didn’t care about who was ruling or who was in opposition or who controlled that checkpoint or who led this militia or that division. All I wanted was for us kids to be left in peace, to play and go to school and work on our hobbies in complete freedom and far away from the grown-ups’ stupidities and their sh*t-eating ways.”

Dost has adroitly juxtaposed a child’s tenderness, the gore of war, and shocking humour with a phantasmagorical element. It is a work that deserves recognition, though some readers may find his use of vulgarity and sexual explicitness difficult to overcome.

However, this is a tale the global audience should not ignore. Often when war is discussed, the loss of childhood is lamented, but is the true weight of this tragedy ever fully understood?

Children perceive the world with broken clarity and understand the hypocrisy of those in power who claim war and terror are necessary and justified.

As Kamiran becomes one with his chalk, not only does his body fracture, but his spirit and soul begin to dissolve.

He wants to tell his story and express his pain through the chalk, yet war is a pernicious force that knows only how to silence.

Noshin Bokth has over six years of experience as a freelance writer. She has covered a wide range of topics and issues, including the implications of the Trump administration on Muslims, the Black Lives Matter movement, travel reviews, book reviews, and op-eds. She is the former Editor in Chief of Ramadan Legacy and the former North American Regional Editor of the Muslim Vibe