Strife-torn South American country Colombia is not only suffering from a new wave of violence but is also facing an energy crisis. Dwindling oil and natural gas production is crimping domestic energy supplies and impacting Colombia’s troubled economy. There is a grave threat of a serious natural gas shortage. A lack of exploration drilling, diminishing reserves and plummeting production are weighing on economically crucial natural gas supplies. The shortage of fossil fuel is exacerbated by rising consumption and natural gas’s increasingly vital role in Colombia’s energy mix.

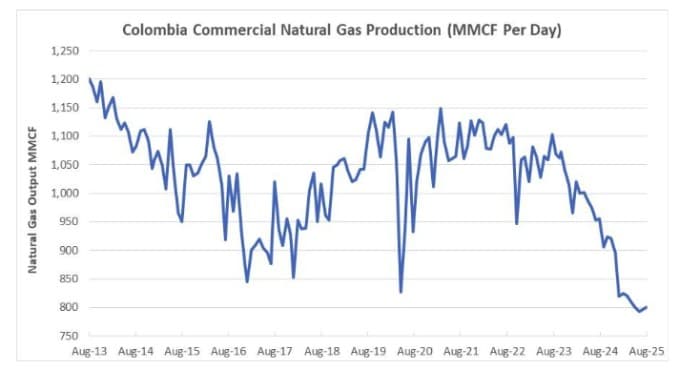

Government data shows Colombia’s natural gas production for August 2025 plunged 16% year over year to 800 million cubic feet per day. The severity of this sharp decline is highlighted by Colombia’s current natural gas production being at its lowest level in over a decade and around 33% less than 2013 natural gas output, as shown below.

Source: Colombia’s National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH).

Indeed, industry insiders, government officials and economists have long stressed Colombia’s pressing need to produce more natural gas, particularly with consumption soaring higher. Over a decade ago, those pundits opined that production of one billion cubic feet of natural gas per day was the minimum economically viable volume.

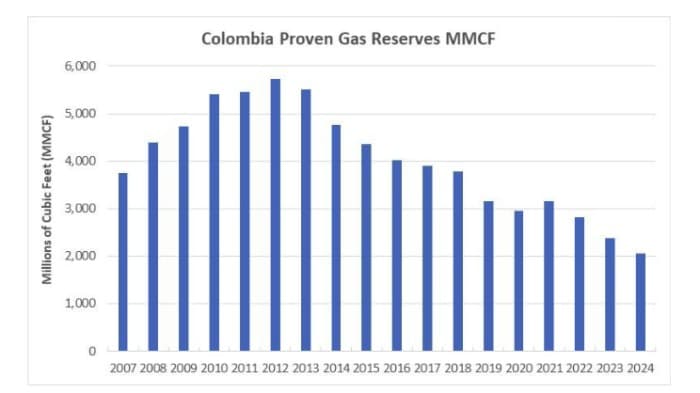

Colombia’s natural gas reserves are also failing to keep pace with domestic demand. Data from the National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH) shows that at the end of 2024, Colombia’s proven natural gas reserves stood at just under 2.1 billion cubic feet. This represents a whopping 13% decrease compared to a year earlier. It is the lowest level in over a decade, with those reserves forecast to only last another 5.9 years at the current rate of production. ANH data, set out in the graph below, shows natural gas reserves have declined every year, except for 2021, since 2012.

Source: Colombia National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH).

Colombia’s proven natural gas reserves will continue to decline at an accelerated rate due to rapidly growing consumption and a lack of hydrocarbon exploration and discoveries in the country. In fact, according to El Colombiano, Colombia has consumed 4,628 billion cubic feet of natural gas over the last decade but only replaced 824 billion cubic feet of the natural gas reserves consumed. The reserve replacement ratio will continue to fall due to the lack of exploration drilling and major discoveries.

Most natural gas produced in Colombia is associated gas derived from oil production. Drillers capture this natural gas, which is a byproduct of lifting petroleum, and reinject it into oil wells to boost reservoir pressure, thereby enhancing recovery. This is an increasingly important oil extraction technique in Colombia because of the rising number of mature oilfields where production has peaked and entered a steady decline. The number of mature wells and decline rates will only increase because President Gustavo Petro has decided to ban exploration drilling by not awarding new contracts.

Those developments underscore the urgency with which Bogota needs to implement initiatives to boost hydrocarbon exploration, expand proven reserves and increase production. Yet, Colombia’s leftwing President Petro, after taking office in August 2022, not only ceased to award new oil contracts but also implemented various policies designed to reduce the country’s dependence on fossil fuels and extractive industries. President Petro made this decision despite natural gas being recognized globally as the fossil fuel of choice due to its low carbon emissions, in order to support the clean energy transition.

Sharp declines in natural gas reserves and production pose a significant threat to Colombia’s power grid. The Andean country, while generating 58% of its electricity from hydroelectric plants, is highly reliant upon natural gas-fired power stations. Regular fluctuations in water levels, caused by climatic events and consequently affecting electricity production, place considerable pressure on an electricity grid already stretched beyond capacity. Indeed, brownouts and blackouts are commonplace across many parts of Colombia’s stretched electric grid, particularly during periods of limited rainfall.

Until early 2025, a severe two-year-long drought, caused by the El Niño climate phenomenon, led to a sharp reduction in electricity production due to plummeting water flows at Colombia’s hydro plants. This drought was so severe that the Mayor of Bogota, Carlos Galán, was forced to introduce water rationing. This pushed the national government to seek other sources of natural gas, as local production was incapable of meeting the additional demand.

The sharp decline in natural gas production is so severe that after decades of self-sufficiency, Colombia no longer extracts enough of the fossil fuel to meet its needs. By 2016, Bogota was forced to start importing liquified natural gas (LNG). Cargoes of the fuel that year, according to the IEA, totaled 429 million cubic feet. LNG imports continue to soar higher, with data from S&P Global showing cargoes hit a record high of 94 billion cubic feet in 2024, almost triple the 36 billion cubic feet imported a year earlier. That means the imported fossil fuel now accounts for around a fifth of all natural gas consumed in Colombia.

It was Colombia’s harsh two-year drought, from 2023 to early 2025, that drove the massive increase in LNG imports during 2024. This severe weather event, triggered by the El Niño climate phenomenon, caused water levels at Colombia’s hydro-plants to plummet sharply, impacting electricity supply. That forced the government to increase the importation of LNG to fuel three gas-fired power plants in Colombia’s north, boosting electricity generation at a crucial moment as hydro power fell significantly.

While the drought ended some months ago, the main industry trade body, The Colombian Natural Gas Association (Naturgas), believes LNG imports will keep climbing. The industry association projects that by 2029, Colombia will be forced to import 56% of all natural gas consumed domestically. According to Naturgas, it is plummeting supply and not rising demand, which is responsible for the widening shortfall. This is due to a lack of exploration drilling to identify new reservoirs, which, along with falling investment, will prevent the development of the new natural gas fields required to boost production.

By Matthew Smith for Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com: