In 2026 the Chess Olympiad and the election for FIDÉ President are due to take place in Samarkand, the ancient city in Uzbekistan. The current President, a supporter of Putin, may face a challenge from his predecessor, Kirsan Ilyumzhinov. Once blacklisted by the United States under President Biden, Ilyumzhinov has since been cleared under President Trump. His claim of Central Asian descent, whether Mongolian or Uzbek, gives him a natural advantage in the contest.

Until their victory in the 2024 Olympiad, Uzbekistan had played almost no role in world chess. Yet it is not a stranger to the game. A thousand years ago the region was part of the Islamic Golden Age. Here was born Avicenna (980–1037), remembered in the West as a physician and philosopher. He wrote hundreds of books, many of which survive, covering medicine, philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, and theology. His Canon of Medicine shaped European learning for centuries.

Later came Tamerlane, or Timur (1336–1405), the conqueror who claimed descent from Genghis Khan and whose mausoleum remains in Samarkand. He invented a larger and more complicated form of chess, with pieces such as elephants, lions, camels and siege engines. It was a game for a warlord who thought nothing should be simple. According to legend, he named his youngest son Shah Rukh while at the board. The name comes from the rook, the chess piece, and also means “king’s face” in Persian.

Shah Rukh ruled after Timur’s death. He moved the capital to Herat and held together much of his father’s empire. Unlike Timur, who spread fear by war, Shah Rukh gained power through trade and diplomacy. His court was rich, orderly, and known for its support of the arts and sciences. Historians remember him less as a conqueror than as a ruler who brought a measure of stability to a violent land.

Chess was close to both men. Timur had a court historian known as Ali ash-Shatranji—literally, Ali the Chessplayer. He was said to be unrivalled at the game. Stories connect him with the “Aladdin” of later fables, though fact and myth are mixed.

So while modern chess barely registered in Uzbekistan until recently, its soil is heavy with memory. Avicenna’s science, Timur’s wars, Shah Rukh’s trade, and even the fantastic chessboards of the Timurid court—these form a background that the current Uzbek team, winners of the last Olympiad, can claim as their own. They conquered not with armies, but with the quiet force of the sixty-four squares.

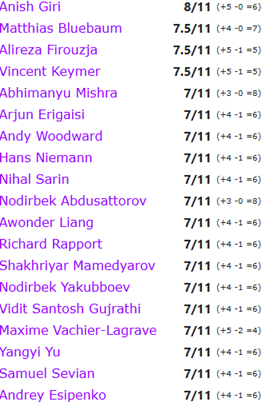

As a warm-up to the Olympiad and FIDÉ elections, to be held next year in Samarkand, Uzbekistan recently hosted there the immensely strong FIDÉ Grand Swiss System qualifier, the top two places from which earn slots in the next world championship Candidates tournament. Anish Giri (Holland) triumphed, with Mathias Bluebaum (Germany) taking the second qualifying berth.

FIDÉ Grand Swiss Tournament

The reigning world champion (the words almost stick in my throat), Gukesh Dommaraju, finished absolutely nowhere in the final table, at one nadir in his fortunes even losing three games in a row.

[Gukesh finished in 41st place with 6 points, out of 116 competitors.]

I blame Magnus Carlsen for this humiliating degradation of the world championship title. By resigning the championship, while continuing to dominate all other competitions, Carlsen has abandoned the field to relative pygmies, not worthy to be mentioned in the same breath as past champions such as Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Botvinnik, Spassky, Fischer, Karpov and Kasparov.

FIDÉ Grand Swiss, Samarkand, 2025, rd. 11

c4 Nf6 2. Nc3 e5 3. Nf3 Nc6 4. e3 Bb4 5. Qc2 Bxc3 6. Qxc3 Qe7 7. a3 d5

A safer choice than, 7… a5!? which, after 8. b4 d6, was successful for White in Keene-Tisdall, Orense, 1977. However, Black could have improved with either 8… e4 or …axb4.

d4 exd4 9. Nxd4 Nxd4 10. Qxd4 c5 11. Qh4 Be6 12. cxd5 Nxd5 13. Bb5+ Bd7 14. Qxe7+ Nxe7 15. Be2 Rc8 TN

Departing from, 15… f6 in the game, Ivanchuk-Karjakin, Wijk aan Zee, 2006.

f3 f6 17. Kf2 Kf7 18. Rd1 Be6 19. h4 b6 20. e4 Nc6 21. Be3 Na5 22. Rd6 Rhe8 23. g4 Nb7 24. Rd2 Na5 25. Rd6 Nb7 26. Rdd1 Na5 27. Rac1 Ke7?

This error marks the point at which the game begins to inexorably slip away from Black. Correct was, 27… Nb3 28. Rc3 c4 29. f4 Kf8 30. g5 Nc5 31. Bxc5+ Rxc5 32. Bh5 Bf7 33. Bxf7 Kxf7, when both players remain very much in the game.

Ba6 Rcd8 29. Rxd8 Rxd8 30. b4 Nb3 31. Rc3 Rd6 32. bxc5 bxc5?

And this is probably the losing mistake. After, 32… Nxc5 33. Bb5 a6 34. Be2 Rc6 35. Bd4 h6 36. Ke3 Bd7 37. h5 Kf8 38. Bd1 Ke7 39. e5 f5 40. gxf5, White without doubt has the initiative, but there remains plenty of play left in the game.

Rxb3 Bxb3?!

This misstep is the final straw, after which White is ruthless in asserting a superior endgame technique. Black’s last chance lay after, 33… Rxa6 34. Rb7+ Bd7 35. Bxc5+ Kd8 36. Kg3 Ra4 37. Bf8 g6 38. Bd6 Ra6 39. Rb8+ Bc8 40. Bc5 Kc7 41. Rb3, when he may be able to hang on by a very thin thread.

Bxc5 Kd7 35. Bxd6 Kxd6 36. g5 Be6 37. Ke3 Kc5 38. Kf4 Kd4 39. gxf6 gxf6 40. a4 h6 41. a5 Bd7 42. Be2 Kc5 43. e5 Kd5 44. exf6 Ke6 45. f7 Kxf7 46. Ke5 Black resigns 1-0

Ray’s 206th book, “

Chess in the Year of the King

”, written in collaboration with Adam Black, and his 207th, “

Napoleon and Goethe: The Touchstone of Genius

” (which discusses their relationship with chess) can be ordered from both Amazon and Blackwells. His 208th, the world record for chess books, written jointly with chess playing artist Barry Martin,

Chess through the Looking Glass

,

is now also available from Amazon.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.