It is not exactly news that France has problems with its political leadership. While they do their best to beat Weimar Germany in political instability, the EU economy is left adrift.

Understandably, some commentators begin looking elsewhere for more attractive economic conditions to report on. The latest example comes from BFM Television and its article from Monday, October 13th:

As France sinks into a budgetary crisis, Portugal expects to generate a public surplus of 0.3% of GDP this year.

The article goes on to laudatorily explain that the Portuguese government

plans to achieve public surpluses of 0.3% of its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2025 and 0.1% next year.

Since France is hard at work trying to become Europe’s fiscal whipping boy, it is not surprising that commentators look with envy at numbers like these from Portugal. However, it is important not to be seduced by the numbers coming out of Portugal and certainly not to let those numbers lead to the conclusion that fiscal austerity is a good policy strategy.

The Portuguese economy is a good example. It has gotten to a point where there are budget surpluses, but only after years of fiscal austerity. I explained part of their struggle four years ago. That austerity quelled domestic demand, leaving the economy without an apparent growth generator.

It was not until the worst of the austerity period tapered off circa 2014 that the Portuguese economy rebounded. This raises a question about fiscal austerity that many in Europe have good reasons to ask today—especially in France: did the fiscal austerity measures lead to the GDP growth that followed, or did they delay that growth?

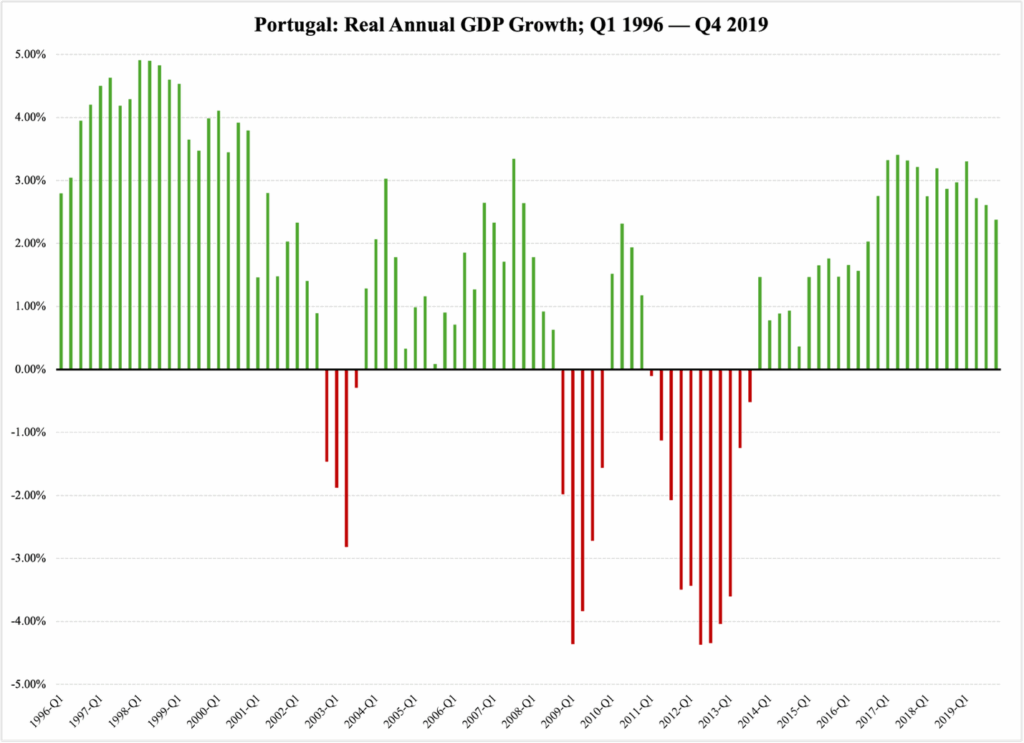

As always, the answer is that austerity delayed the rebound in economic growth. Figure 1 below provides a longer-period context, from 1996 through 2019, showing exactly what the toughest austerity period did to Portugal’s economy:

Figure 1

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Of the three episodes with negative growth—a shrinking economy—the first was a traditional economic downturn. The Millennium recession in 2001-2002 was really just a mild and brief economic slump. The second episode, the Great Recession, is often referred to as a ‘financial crisis’; in reality, it was a finance market correction that exploded into a depression-like experience for many countries—and the reason was a first, large-scale application of austerity policies.

As I explain in my book Industrial Poverty (Gower 2014), during the Great Recession, the EU, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund subjected a slew of European countries to invasive fiscal monitoring. In some of them, this resulted in severe budget cuts and growth-crippling tax increases.

Portugal was one of those countries. In the eyes of the EU, the ECB, and the IMF, public finances were so bad that they strong-armed the government in Lisbon into implementing a series of austerity packages. On at least one occasion, their demands were backed up by the threat from the EU to put a €78 billion package of emergency fiscal aid on the line if the Portuguese parliament did not approve one of many serious austerity packages (ibid., pp. 134-136).

The result of the austerity policies is visible in the third episode of economic decline: the most protracted episode of GDP decline over the past 30 years. In 2014, the real ten-year growth of the Portuguese economy was zero: in terms of standard of living, Portugal’s families had made zero advancements in ten years.

After 2014, when austerity tapered off (but never really went away), Portugal’s economy did relatively well, on occasion even exceeding 3% real GDP growth. The two pandemic years, 2020 and 2021, left the country’s economy 1% smaller in real terms, and the recovery from the artificial economic shutdown stretched out into 2022.

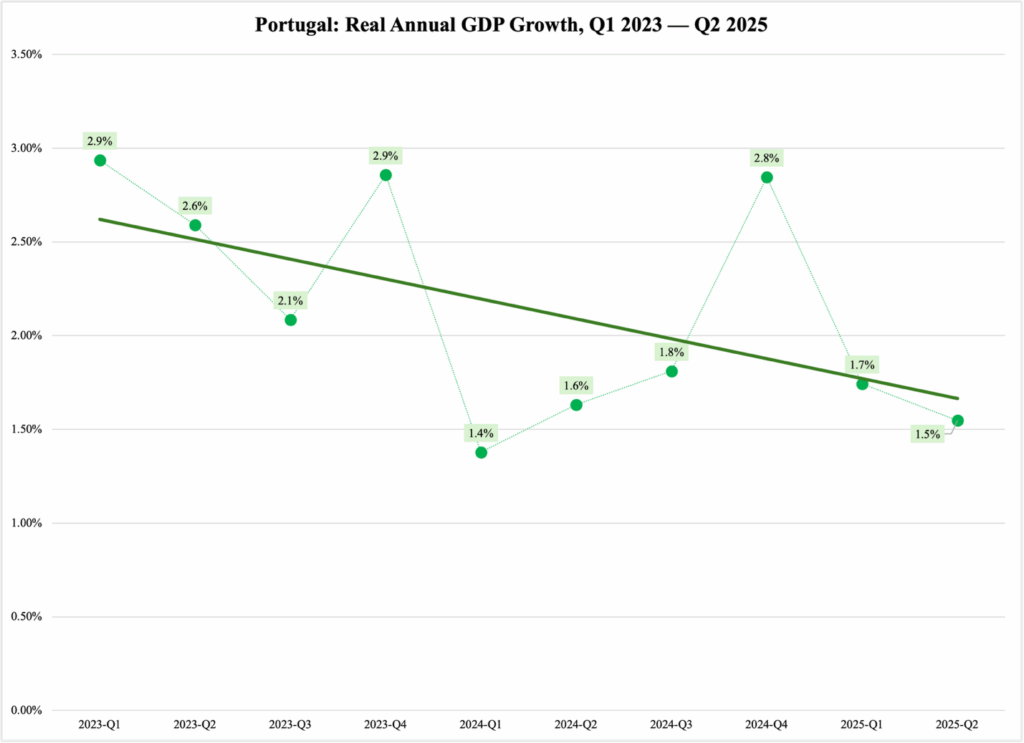

To see what the Portuguese economy is capable of today, we need to consider 2022 part of the pandemic episode. Starting in 2023, Figure 2 tells us a relatively bleak picture of where Portugal is heading. Real average annual growth for the ten quarters covered here is a meager 2.1%, and—as the solid trend line indicates—the Portuguese economy is slowly sinking into stagnation:

Figure 2

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Why is this happening? If the budget surplus that the French commentator spoke so favorably about is supposed to be good for the Portuguese economy, then how come it is actually drifting into economic stagnation?

One reason for this is austerity itself. When the government raises taxes and cuts spending, it withdraws money from the economy. Economic theory says that this will lead to lower interest rates, as the government borrows less and therefore reduces its absorption of savings. This, in turn, is expected to stimulate private-sector activity—first and foremost capital formation by private businesses—and generate a new wave of economic growth.

The problem with this is that the correlation between lower interest rates and business investments is weak at best: in my own research I have never found that correlation to be higher than 10%. In other words, for every €100 that businesses invest, only €10 can be explained by lower credit costs.

The other 90% is explained primarily by fluctuations in total demand in the economy—a variable that falls as a result of austerity. However, this also means that when the austerity period is over, or the measures are scaled back significantly, there will be room in the economy for increased spending, which in turn will lead to a surge in business investments.

Again, Portugal is a case in point. Measured in fixed prices,

From the mid-1990s through the Great Recession, gross fixed capital formation—the technical name for business investments—accounted for more than 20% of the Portuguese economy;

During the toughest austerity years, that share plummeted to 15% of GDP—and this was during a period in time when Portugal’s GDP was declining;

Once austerity was scaled back, businesses accelerated capital formation again, slowly but steadily bringing it back up to 20% of GDP.

The lesson to be learned from this, for the French and for others, is that if you are going to use austerity to bring balance to your consolidated government finances, make sure the economy can endure a period of painful declines in the standard of living. If people in general are willing to accept that, and if you are convinced that there is no other alternative, then plan for all kinds of measures to stimulate the private sector once austerity is over.

Such measures need not—and indeed should not—involve subsidies. A far better way forward is to cut red tape for the business sector, remove fees, and make strategic tax cuts.