Blame games, tit-for-tat threats, off-again on-again meetings between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping, and wild tariff swings seem to be the recent order of the day.

According to former government officials and analysts, however, this should come as no surprise – it’s just the price you pay when diplomatic norms are brushed off.

In the latest twist in the saga, Trump on Friday swung from tough to conciliatory, appearing to reverse threats made a week earlier to cancel a planned upcoming meeting with Xi in South Korea and impose an additional 100 per cent tariff on all Chinese goods.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

Trump’s salvoes followed Beijing’s move a day earlier to expand export controls over strategic rare earth minerals and related technologies.

Those in turn were triggered by Washington’s move late last month to expand sanctions on companies at least half owned by blacklisted firms on national security grounds.

“This is what happens when there’s a lack of clear communication. Both sides have misread the other,” said Zack Cooper, a fellow with the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

“People in the US system did not understand how angry Beijing would be about the 50 per cent rule on September 29. And people in Beijing didn’t understand how angry Washington would be about its October 9 actions.”

Amplifying recent trade gyrations that have roiled markets and frustrated global business planners are the very different political cultures that define the Xi and Trump administrations, analysts said.

The sweet spot for stability-obsessed Beijing is a series of carefully choreographed meetings over months at successively more senior levels, leading to a summit or Politburo-level agreement with every detail planned down to camera angles.

“They don’t tend to go for spontaneity,” said Michael Froman, president of the Council on Foreign Relations. “Everything tends to be well scripted before the meeting. They want to manage any downside risk or embarrassment for their leader.”

“Traditionally, within the Biden administration, there was a very strong channel between the National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and his counterpart Wang Yi,” added Froman, former US Trade Representative during the Barack Obama administration.

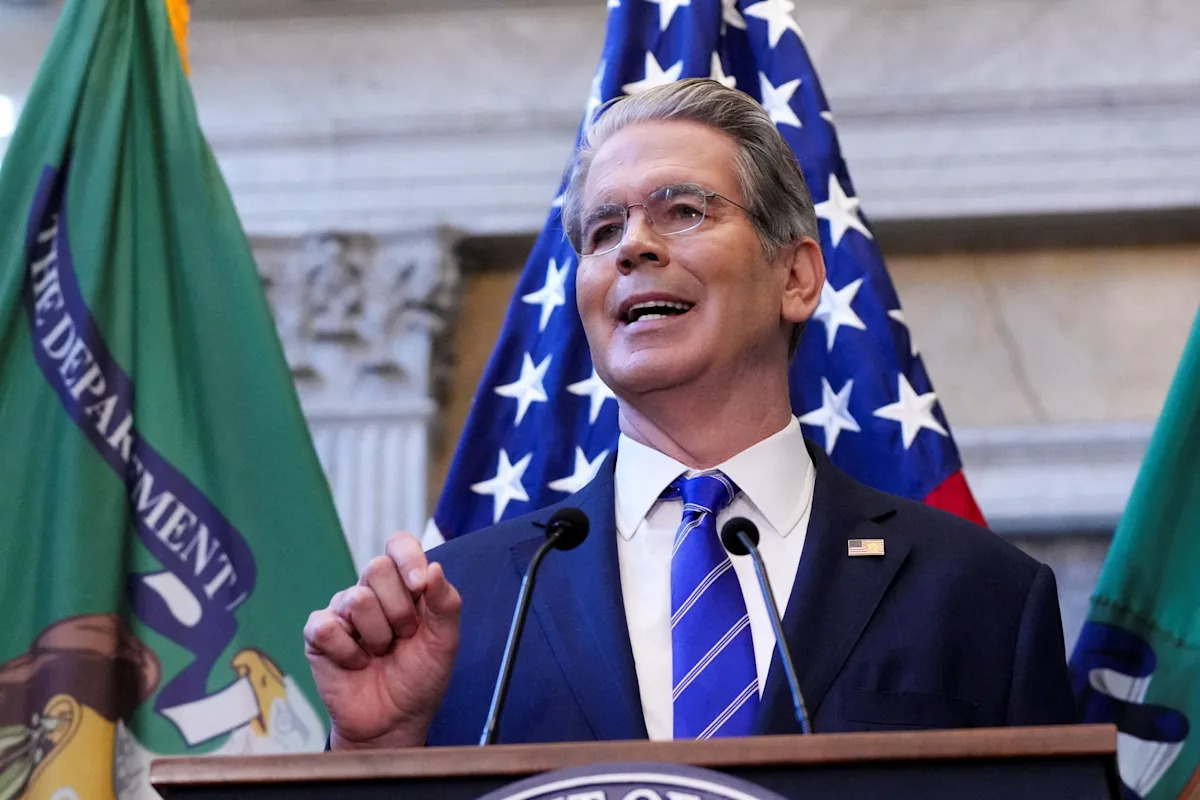

US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent speaks at the annual meeting of the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday. Photo: Reuters alt=US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent speaks at the annual meeting of the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday. Photo: Reuters>

Trump, in marked contrast, touts his ability to disregard norms and established niceties, often bristles at “process” or being upstaged by underlings and places great weight on his personal negotiating skills, unpredictability and perceived skill at making last-minute deals by going with his “gut”.

The mercurial president’s no-holds-barred style, echoed by his lieutenants, is also viewed in China as discourteous and highly undiplomatic in a nation where face and public respect for its remote, one-party leadership is deeply ingrained.

Trump’s approach is consistent with someone who built his political career on personal attacks and catchy nicknames.

“Highly respected President Xi just had a bad moment,” Trump posted earlier this month. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent followed that up this week by referring to Chinese Commerce Ministry negotiator Li Chenggang – Xi’s point man – as “unhinged”, “very disrespectful”, and suggesting that Li showed up in Washington uninvited.

“Perhaps he’s gone rogue,” Bessent added.

As the economic giants have become increasingly indignant at the other side, each has publicly cherry-picked points to bolster their own case, often appearing all but deaf to the other side’s viewpoint, with little if any backchannel reality checks. Trust, once broken, is difficult to rebuild, analysts concluded.

From Washington’s perspective, the latest downward spiral after a few months of relative calm started with China’s rare-earth export curbs, leading the administration to accuse Beijing of a hostile, unprovoked outrage.

That led Trump to issue his flurry of threatened responses a week ago centred on elevated tariffs, the possibly cancelled Xi meeting and added company sanctions.

For Beijing, however, the starting gun was fired days earlier when the US Commerce Department issued a new rule expanding its restricted export list, known as the Entity List, sanctioning a wide swathe of additional Chinese companies.

China, feeling similarly attacked without provocation, defended its rare-earth response, saying it was “defensive”, leading to accusations the US was creating “unnecessary panic” and blowing it all out of proportion.

In its mind, the expanded US export restrictions also violated what it saw as an implicit ceasefire hammered out in Spain last month.

“Beijing believed that there was a tacit agreement coming out of Madrid to avoid just such escalatory actions,” said Paul Triolo, partner with Washington consultancy DGA-Albright Stonebridge Group.

He added that the 50 per cent rule would affect as many as 10,000 Chinese companies, and “is not, as the Commerce Department apparently portrayed to the rest of the administration, a minor closing of loopholes”.

Part of the problem may be differences within the Trump administration, resulting in mixed messages that complicate the ability of China – as well as markets and traders – to read US intentions, analysts said.

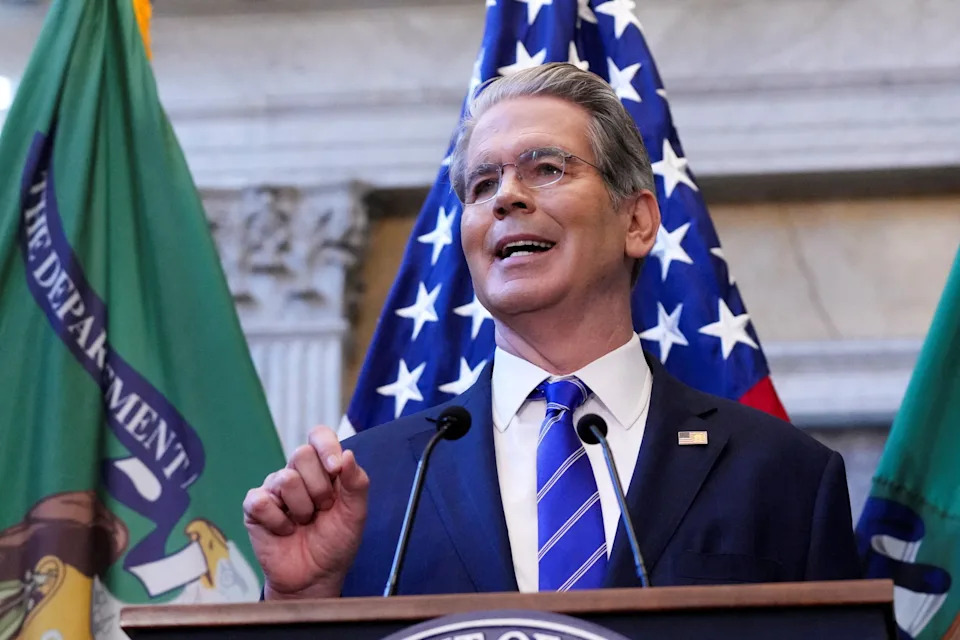

In November, Fox News reported “nasty, Hunger Games-style” jockeying between Treasury Department’s Scott Bessent, who now leads the China talks, and Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, whom it described as “the brass-knuckled” Wall Street chief executive who lost out to Bessent for the Treasury role.

US technology policy toward China is complex, added Triolo, and lacks a coordinating agency. This allows individual officials to push their agendas without considering other agencies or broader trade negotiations.

“I suspect that there is very substantial infighting and that it’s part of what’s going on right now,” said Cooper.

“It’s pretty opaque to me, even though I know instinctually that it’s probably a big driver of what’s going on … most likely it’s very nasty.”

Fox News described US Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick as “the brass-knuckled” Wall Street chief executive. Photo: EPA alt=Fox News described US Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick as “the brass-knuckled” Wall Street chief executive. Photo: EPA>

But Washington is not alone, added Cooper, amid evidence of different interests reflected in Beijing’s statements by its Commerce Ministry.

Some, however, say Washington’s differences are more effective than they appear, with Bessent playing “good cop”, Lutnick playing “bad cop”, and Trump making the final decision.

As the US-China game of chicken has intensified, some say Beijing is using tactics and wielding leverage with its rare-earth threats, mirroring Washington’s use of strict export controls on chips and tools.

“This is a classic case of ‘what goes around, comes around,'” said William Reinsch, former undersecretary of Commerce during the Bill Clinton administration. “The US should have seen it coming.”

China has a “long history of responding in kind, and this continues that tradition”, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies senior advisor added.

China controls nearly 90 per cent of global rare-earth processing – critical for manufacturing everything from AI chips to fighter jets – and its new curbs require approval to export even trace amounts of rare earths and data on their intended use.

Another trade complication is the struggle for AI supremacy. China may have increased its rare-earth restrictions less from outrage than to gain leverage in advance of the planned Xi-Trump meeting, said Christopher Padilla, former Commerce Department undersecretary during the George W. Bush administration.

“It appears that China is looking for a trade relaxation of American limits on AI in exchange for China allowing exports of rare earths,” said Padilla, a senior adviser at Brunswick Group.

He added that US semiconductor restrictions and Chinese rare-earth limits are both global, extraterritorial, require re-export licenses even for small amounts and presume denial for military applications.

Despite Trump’s indication on Friday that his meeting with Xi was back on the radar, a development the world will be watching expectantly, few see much chance of a comprehensive trade deal anytime soon, given all the bad blood, miscommunication and lack of groundwork.

While Beijing has yet to confirm, Bessent said on Friday he expects to meet his Chinese counterpart, Vice-Premier He Lifeng, in Malaysia “probably a week from tomorrow” to help set the stage for a potential meeting.

But the South Korean sit-down could see an extended truce on tariffs, temporary forbearance on export controls, and short-term confidence-building measures like Boeing purchases, said Padilla.

And China might agree to buy US agricultural goods in return for some easing of US restrictions, said Bonnie Glaser, managing director with the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

“In the meantime, Trump can use the ‘billions’ of dollars he is bringing into US coffers from tariffs to pay American farmers, which is what he did in his first term,” she added.

This article originally appeared in the South China Morning Post (SCMP), the most authoritative voice reporting on China and Asia for more than a century. For more SCMP stories, please explore the SCMP app or visit the SCMP’s Facebook and Twitter pages. Copyright © 2025 South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

Copyright (c) 2025. South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.