Show summary Hide summary

Britain has quietly reached a new, troubling milestone: authorities have authorized a decision that effectively says visiting Jews cannot be guaranteed safety on our streets. The spectacle around the ban on Maccabi Tel Aviv supporters for the Europa League tie at Aston Villa exposes more than a single event — it reveals how fear and intolerance are now shaping public policy and civic life.

This episode is less about football than about who a country chooses to protect. When officials opt to exclude a group from attending an event because of the likely hostility they would face, they send a message about where responsibility and blame sit in our society.

What happened at Villa Park and why it matters for Jewish safety

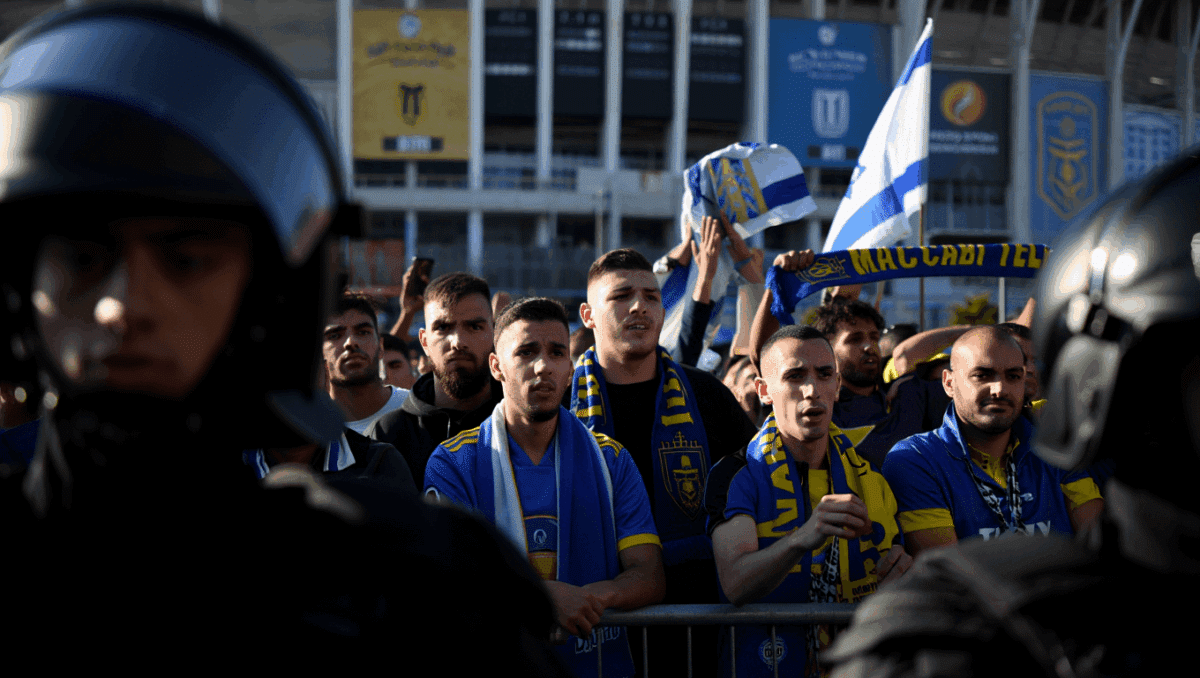

The match between Aston Villa and Maccabi Tel Aviv, scheduled for November 6 at Villa Park in Birmingham, was stripped of travelling supporters after the local Safety Advisory Group advised against admitting away fans. West Midlands Police backed the decision, citing concerns about potential protests and their ability to respond. In practice, that meant Israeli fans were told not to travel — or, put bluntly, kept out for their own protection.

This is not merely an operational choice; it is a public admission that parts of Britain are not secure for Jews who are visiting from Israel. The ban followed violent attacks on Maccabi fans in Amsterdam the previous November, where groups set out to assault supporters, using explicitly anti-Jewish language and organizing in messaging channels. Those images and reports clearly informed the risk assessment — but the response chosen was exclusion rather than confrontation of the attackers.

How past violence shaped the decision — and why the logic is dangerous

Officials point to real and frightening precedents. Fans of Maccabi who travelled to European fixtures have been targeted by mobs in other cities, sometimes described as coordinated hunts by attackers who used ethnic slurs and violent intent. Such incidents legitimately raise concerns about crowd safety and policing capacity.

But the chain of reasoning that follows — if potential attackers might arrive, we will prevent the potential victims from attending — is morally and politically fraught. It reverses the responsibility for public safety onto those who would be harmed rather than those who threaten harm. That shift can harden into policy and practice unless challenged.

Why excluding visitors encourages further abuses

It normalizes the idea that certain groups should stay away from public spaces for their own safety.

It rewards aggressive behavior by implicitly conceding that intimidation works.

It undermines trust in law enforcement to protect everyone equally.

When a state tolerates the removal of rights from a minority to appease a mob, it is making a dangerous bargain. The logic is circular: if you ban a group to prevent disorder, you risk turning the ban into precedent, inviting similar demands whenever a group is threatened or unpopular.

The political fallout: who applauded and who pushed back

The decision did not occur in a vacuum. Some local politicians and activists who have criticized Israel vocally welcomed the ban. For example, Birmingham MP Ayoub Khan publicly welcomed the move, arguing that spectator sport should be open to all but hinting at conditions. That kind of conditional support underscores a broader political frame: the rights of a particular community are being negotiated in the arena of public sentiment.

At the same time, national leaders and party figures have condemned the ban. Labour leader Keir Starmer called the decision wrong and urged policing and political action to ensure that fans can attend without fear. His words underscore a tension between rhetoric and remedy — condemnation of anti-Semitism is common in public statements, but reversing a policy that erects barriers to attendance requires immediate operational commitment.

Practical alternatives authorities could pursue

Rather than excluding visitors, there are several steps clubs, governing bodies, and police could consider to protect supporters and uphold civil rights:

Postpone or relocate fixtures where credible intelligence suggests unavoidable mass disorder.

Deploy sufficiently resourced policing and stewarding to separate groups and deter troublemakers.

Work with UEFA, clubs, and governments to vet and sanction organized groups that incite violence.

Establish clear protocols that prioritize the protection of vulnerable visitors rather than their exclusion.

Use targeted legal action and intelligence operations against individuals or networks spreading threats online and offline.

Canceling a match entirely may sometimes be the only safe option; banning a particular nationality or religion from attending is a far worse precedent. The former treats danger as a temporary operational reality. The latter treats an entire group as a persistent problem to be managed by exclusion.

What the decision signals about societal priorities and anti-Semitism

How a country treats its Jewish citizens and visitors has long been a measure of its civic health. Historically, laws or customs that push Jews to the margins — social, physical, or legal — have been an indicator of deeper problems. The Villa Park ban invites a hard question: are we now inclined to value the peace of those who would aggressively exclude Jews more than the safety and freedom of Jews themselves?

The term Israelophobia has been used to describe a mixture of anti-Israel sentiment and, at times, outright hostility to Jewish people. When criticism of a state bleeds into dehumanization or violent intent toward people associated with that state, it becomes indistinguishable from anti-Semitism. Public policy must resist that slippage.

Signs to watch in the weeks ahead

Whether national and local authorities change the decision or put in place credible protective measures for future matches.

How football governing bodies and clubs respond to calls for stronger safeguards.

Whether incidents of intimidation are met with prosecution and public condemnation targeting perpetrators, not victims.

The risk is that in easing short-term tensions we codify a pattern that erodes civil equality over time. That erosion is not merely symbolic; it reshapes who feels free to travel, worship, and participate in public life.

Voices behind the article

Brendan O’Neill writes on politics and culture and hosts a podcast. His recent work examines the social and political fallout of the week of 7 October and related tensions. He publishes regularly and is active on social platforms where he discusses civil liberties, identity politics, and contemporary controversies.

You might also like:

Robert Johnson is a dedicated columnist focusing on political and social debates. With twelve years in editorial writing, he provides nuanced, well‑argued perspectives. His commentaries invite you to form your own views and engage in critical issues.

Give your feedback

★★★★★

Be the first to rate this post

or leave a detailed review