Imagine it: You’ve worked a long shift, turned the lights out and settled into bed, when all of a sudden the sky outside your window lights up as if it’s daylight.

This is what could happen if a U.S. company has its way.

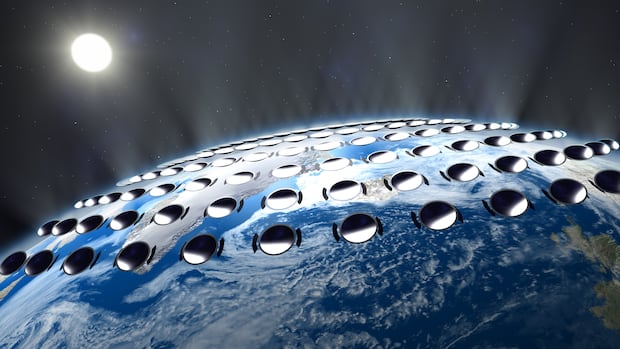

Reflect Orbital is looking to send giant mirrors in space to “sell sunlight after dark.”

It’s a plan that’s causing alarm among astronomers who are already concerned about the loss of the night sky due to satellite constellations — hundreds to thousands of satellites belonging to one company, most often providing internet services — and overall light pollution.

But the California startup says their plan could help solve energy issues as well as provide lighting for situations like disaster rescue plans and more.

Astronomers aren’t buying it.

Aaron Boley, an astronomer and associate professor at the University of British Columbia, said there are “basic misunderstandings or willful misrepresentations” on the company’s website.

“They were talking about reducing light pollution by having this giant light from space. And it really seems like they’re trying to suggest that because it’s natural sunlight, it’s not like pollution.”

Reflect Orbital says its space mirrors could provide solar farms with additional sunlight after the sun sets. (Ted Shaffrey/The Associated Press)

The company — which filed a request with the U.S. the Federal Communication Commission to launch its first satellite, EARENDIL-1 — is proposing using the satellites to beam down reflected sunlight on specific locations, such as solar farms after the sun has set.

Reflect Orbital has proposed a few different sizes of satellites, ranging from 10 x 10 metres, 18 x 18 metres and even 54 x 54 metres.

But even at the top size, some experts say that in order to provide enough sunlight to a solar farm, thousands of satellites would be needed.

“If you were to do the midday sun for instance, you would need a mirror that — from the ground — looked like it was the same size as the sun itself in the sky,” said Michael Brown, an associate professor in astronomy at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

“That’s many kilometres across when it’s up in orbit. Now, no one’s going to launch a mirror that’s many kilometres across, so what they do is they launch multiple smaller mirrors. And Reflect Orbital’s talking about 54-metre-square mirrors. And to just produce 20 per cent of the midday sun, it looks like you need about 3,000, possibly more of these mirrors.”

Reflect Orbital did not reply to requests for comment for this story.

Not a new concept

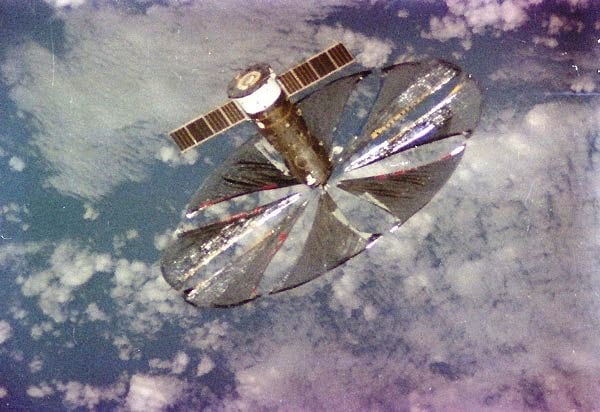

The idea of a space mirror isn’t a new one, which was first proposed in the 1920s. On Feb. 4, 1993, Russia deployed Znamya 2, a space mirror 25 metres in diameter that ended up producing a five-kilometre bright spot. A few days later, it burned up over Canada.

Znamya-2 after its deployment in February 1993. The photo was taken from the Russian space station Mir. (RSC Energia/Wikipedia)

The U.S. and the European Space Agency have also made such proposals, though none so far have come to fruition. Some say it’s because it’s not feasible.

So why is it still so appealing?

“With the proliferation of objects in orbit, there’s a mentality that if you can do something from space, you should do something from space,” Boley said. “And I think that is driving part of this idea.”

He explained that in order for the mirrors to work, the satellites would have to be on a polar orbit — which is like a ring moving from the south to north poles. That would take the satellites right over Canada.

“There’s this other issue of like shining light when you simply don’t want it there … so because we have this sun-synchronous design, then we will be having these satellites just sweeping across Canada as twilight sweeps across Canada,” he said. “And so Canada should be very vocal about that.”

Consequences

Reflect Orbital has estimated the light produced by its mirrors would extend several kilometres across.

There’s concern over how that could impact not only people who don’t want the light, but also wildlife.

The Fundy-St. Martins area has rare darkness, making it a prime location for celestial viewing.

John Barentine, founder of Dark Sky Consulting, said there’s a lot that’s unknown about Reflect Orbital’s technical details. However, he added, information the company has disclosed suggests it will have unintended consequences.

“These objects will appear like very bright stars in the sky moving slowly as seen from potentially hundreds of miles or kilometres away from the spot on the ground where the light appears,” he said.

“It’s happening at a time when the world is dark. The expectation of [animal] biology is that the conditions will be dark around them. I worry a bit that if you are, say, a migratory bird — who we now know are navigating by the stars at some level — that this could be very disorienting.”

Then there are implications for observatories, both professional and amateur.

“Reflect Orbital says we’re definitely not going to light up your observatories, but if I have bright objects that look like stars moving through the sky far from where the beam is reaching the ground, if it’s anywhere close to an observatory, that’s still a problem,” Barentine said.

Brown, of Monash University, is also concerned about unintended radio interference from the satellites. Recently it was discovered that SpaceX’s Starlink satellites are creating noise at radio observatories.

But there’s more that distresses him.

“I’m also more concerned, oddly enough, I’d say from a sort of almost an aesthetic point of view. That I sort of like the sky being sort of this shared wilderness,” he said.

“If you go somewhere where it’s nice and dark and look at the night sky and have these constant reminders of technology, I think that’s a bit of a loss.”