Their View: Fifth-grade politics

From Where I Sit

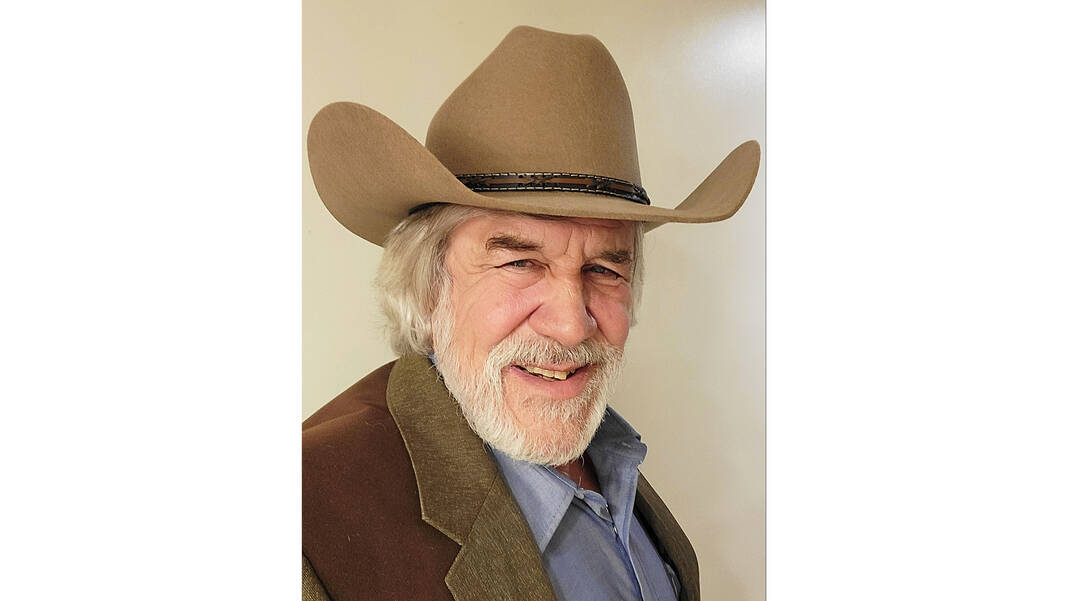

By Chris Gibbs

Contributing columnist

It’s hard to argue that our political environment hasn’t devolved into little more than child’s play on a national stage. Today, actions once reserved for children at recess are now labeled as mean girls, bravado, bullying and memes. So, one has to ask — did you learn everything you need to know about today’s politics on the playground in fifth grade?

Back then, kickball and lunch table cliques were actually early lessons in persuasion, manipulation, fairness and power. When we were 10 years old and couldn’t yet grasp the concept of a democracy, we now know we were living in a miniature version of it. A version complete with its own rudimentary playground rules of hierarchies, negotiation and consequence, all playing out between the recess bell.

The currency of politics

Whether the Roman Empire of 27 BC, or the “whatever this is” of 2025, power and popularity have always been the currency of politics. On the playground, everyone knew who held the power to hold court, pick teams and determine who played first. And yes, they also determined who got left out, left behind and marginalized. No different than today, when influence can outweigh fairness and charisma can trump competence. On the playground, the loudest and most confident child didn’t necessarily have the best ideas, but they usually got the most attention.

There were alliances and factions. The playground was full of them. Whether it was the kickball kids, the jump-rope joiners, the monkey-bar mavericks or the basketball bandits, these groups had their hierarchies of leaders, loyalists and occasional rebels. When groups clashed over who got the basketball court or which game took priority, we learned the art of negotiation and coalition-building. Budding real leaders may have practiced the art of compromise to share court time, or more likely, form temporary partnerships to defeat a common rival. It was elementary-school geopolitics. Those alliances were about sports or swings back then, but the principle is the same today. Political power in 2025 depends on who you can bring to your tribe and how effective you are at keeping them there.

Rules and consequences

Every playground had spoken or unspoken rules and norms. And every playground had enforcers. Our referees were teachers, teacher’s aids and sometimes older kids who could and would step in to restore order. But even that trifecta couldn’t be everywhere all the time. Those times were our first introductory class on self-governance. We learned that kids, like adults today, separate into three distinct groups of order: Those who follow the rules because they are the rules; those who follow the rules only when someone is watching, and those who break the rules not to suffer the consequence, but to test a boundary to judge its durability.

But it’s that kid who perpetually yelled, “It’s not fair,” who drives home the point for me. The same clamor of moral outrage that rings loud today in our political debates was the early clarion call that justice for all can only be achieved through shared trust that we all will follow the playground rules. Today, we know those “rules” as the law, and the consequences of breaking them as accountability.

Justice in leadership

We also learned about bullying and resistance. Some would try to control others through intimidation, fear and coercion. We remember them — I remember them. Like the kid who always took the best ball, cut in line or spread rumors to hold onto influence. Many kids sat silent until someone finally said, “Enough.” That was the moment when courage confronted unfairness head-on. Standing up to a bully on the playground wasn’t just an act of defiance; it was a small-scale civics lesson on how to demonstrate justice, leadership and moral responsibility. Today, grown-up politics offers the same opportunities to demonstrate the “justice” in leadership.

Finally, the playground taught us the importance of inclusion and empathy. The best days out there on the blacktop were when everyone got to play, when the lanky kid finally got picked first, and when fairness outran favoritism. The lessons of fairness, empathy and respect are the foundation of good retail politics. They remind us that governance isn’t just about winning; it’s about ensuring everyone has a voice and a chance.

Looking back now, it is clear that the playground was our first classroom in human behavior: how power works, how alliances are formed and how fairness is tested. The only thing different now is the stakes.

So the question today is not “Did you learn everything you need to know about today’s politics on the playground in fifth grade?” it’s “Did you learn anything at all from it?”

And that’s the way I see it from where I sit.

Gibbs is a farmer and lives in Maplewood, Ohio. He and his family own and operate 560 acres of crops, hay, and cattle. Gibbs is retired from the United States Department of Agriculture and currently serves as president of the Gateway Arts Council, chairman of the Shelby County Democratic Party, chairman of the Ohio Democratic Party’s Rural Caucus, and president of Rural Voices USA and Rural Voices Network.Chris Gibbs is a farmer and lives in Maplewood. He and his family own and operate 560 acres of crops, hay and cattle. Gibbs is retired from the United States Department of Agriculture and currently serves as president of the Gateway Arts Council, chairman of the Shelby County Democratic Party and president of Rural Voices USA and Rural Voices Network.

Gibbs is a farmer and lives in Maplewood, Ohio. He and his family own and operate 560 acres of crops, hay, and cattle. Gibbs is retired from the United States Department of Agriculture and currently serves as president of the Gateway Arts Council, chairman of the Shelby County Democratic Party, chairman of the Ohio Democratic Party’s Rural Caucus, and president of Rural Voices USA and Rural Voices Network.Chris Gibbs is a farmer and lives in Maplewood. He and his family own and operate 560 acres of crops, hay and cattle. Gibbs is retired from the United States Department of Agriculture and currently serves as president of the Gateway Arts Council, chairman of the Shelby County Democratic Party and president of Rural Voices USA and Rural Voices Network.