The White House’s East Wing isn’t Donald Trump’s first tear-down. He;s been raising dust and outrage since the 1980s.

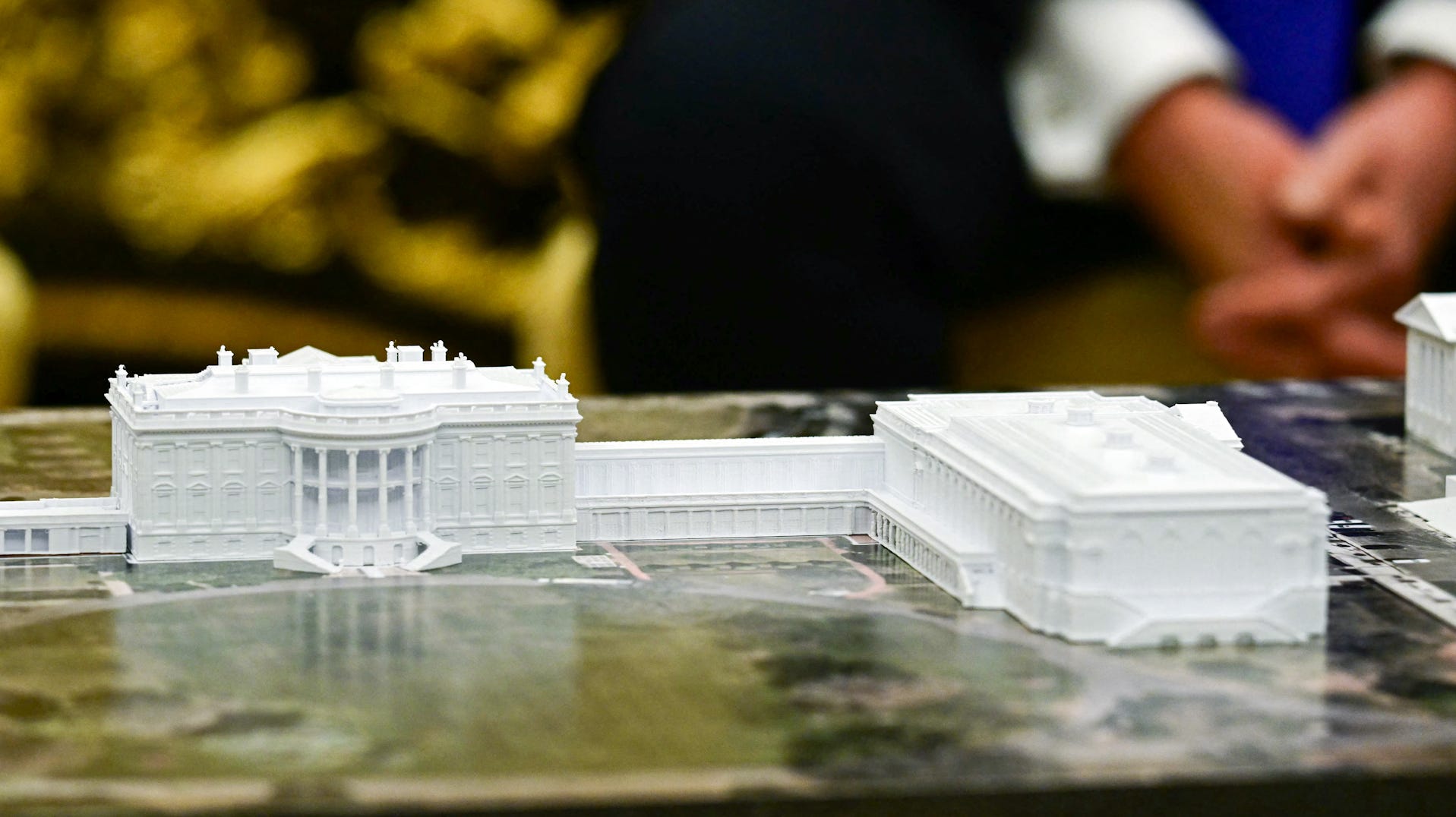

Trump unveils double decker White House ballroom model

President Donald Trump revealed a model of the new double decker White House ballroom, saying he thinks it will be one of the world’s greatest.

NEW YORK – President Donald Trump‘s controversial move to build a $300 million White House ballroom isn’t the first time the billionaire builder has ruffled feathers with a wrecking ball.

The demolition of the East Wing to erect a 90,000-square-foot presidential banquet hall has drawn outrage from groups like the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the American Institute of Architects, not to mention former first lady Hillary Clinton and members of Congress.

But Trump has a history of skirting rules and shredding promises going back to his days as a second-generation New York real estate developer. Despite the White House’s status as a unique symbol of the United States, Trump has decades of muscle memory in barreling past opponents to build what he wants.

“He is of the school of developers who don’t ask for permission and don’t ask for forgiveness,” said Richard Emery, a prominent attorney who chairs a Manhattan cultural preservation group.

Amid dust and despair over the White House demo job, Trump wrote on Oct. 20 that “the East Wing is being fully modernized as part of this process, and will be more beautiful than ever when it is complete!” Trump aides called complaints over the new ballroom – nearly double the size of the current White House, including its basement floors – nothing more than “manufactured outrage.”

‘Monstrous carbuncle’

Critics of Trump’s efforts say their outrage is 100% organic. The cavernous ballroom “is wholly unnecessary,” Peter Smirniotopoulos, a founding board member of the Washington Architectural Foundation, told USA TODAY. “It is completely out of scale and will dwarf the original White House building.”

Quoting a 1980 speech by Britain’s Prince (now King) Charles about a proposed addition to the National Gallery of Art in London, Smirniotopolous called Trump’s ballroom “a monstrous carbuncle on the face of an old and elegant friend.”

Heritage experts say Trump should have gone through the National Capital Planning Commission and the Commission of Fine Arts to approve his ballroom plans before leveling the East Wing, which was first built in 1902. The East Wing has traditionally been used as office space for the first lady.

Whatever the rules, history shows that, in the face of cultural and regulatory opposition, Trump has “always gotten his way, pretty much,” said Hank Scheinkopf, a longtime New York Democratic political consultant.

Fifth Avenue frieze-out

On July 31, Trump assured Americans his ballroom wouldn’t so much as scratch the White House. “It won’t interfere with the current building,” he said. “It’ll be near it but not touching it and pay total respect to the existing building, which I’m the biggest fan of.”

Flash forward to today, and the patch of flattened earth where the White House East Wing used to be. The turnabout would come as no surprise to old-timers at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan. They too have seen Trump’s assurances turn to rubble.

In 1980, Trump bought the site of the bankrupt luxury department store Bonwit Teller on Fifth Avenue and East 56th Street, next door to Tiffany & Co., and announced plans to raise his 58-story flagship Trump Tower there, in the heart of the Big Apple.

Before leveling the place, though, the future president, then in his mid-30s, promised to preserve two Art Deco friezes depicting partially clothed women that adorned the building’s upper facade, as well as a 265-square-foot decorative bronze grill installed over the entrance for donation to the Met museum.But when crunch time came, the irreplaceable friezes got crunched – jackhammered off the wall at Trump’s order, like so much brick and mortar.

The geometric brass grill went missing too. “It’s not a thing you could slip in your coat and walk away with,” noted Otto Teegan, the artist who had designed the piece fifty years earlier. (A Trump biographer later wrote it had been cut away with blowtorches.)

Amid the uproar, Trump said unidentified experts had found the friezes to be worthless (despite an appraisal valuing them at $200,000, or $832,000 in today’s money); that saving them would have cost half a million dollars (despite an earlier estimate from his camp of $32,000); and that preserving them would have put pedestrians in danger.

“The process of trying to redeem or trying to save things of little or no artistic merit…was to me not worth the safety of peoples’ lives,” Trump told an interviewer.

Trump later paid a settlement of nearly $1.4 million over the use of 200 undocumented Polish workers to demolish Bonwit Teller, some of whom were paid just $4 an hour and others who were stiffed on their wages.

“We worked without masks. Nobody knew what asbestos was,” one of the workers later told the Times. “I was an immigrant. I worked very hard.”

The Commodore sinks

In the late 1970s, Trump joined with the Hyatt hotel chain to renovate and reopen the shuttered Commodore Hotel, next to Grand Central Station. It was his first big Manhattan deal, financed by a 40-year New York taxpayer subsidy.

Trump and Hyatt gutted the empty Commodore and turned it into a busy venue on one of New York’s signature intersections. But they clad their new hotel in black mirrored glass, yanking the site out of step with the surrounding neighborhood’s architecture.

While architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable praised the new hotel’s atrium as “one of the handsomest public spaces in New York,” others scorned the exterior, which today still gleams like Darth Vader’s headpiece at an otherwise classy Midtown block.

The Architectural Guidebook to New York City calls the hotel “an inexcusable outrage…situated as it is between two masterpieces, Grand Central Terminal and the Chrysler Building.”

The place was “the sort of flashy hotel one would expect in Atlanta or Houston, but certainly not in New York,” critic Paul Goldberger wrote in The New York Times.

A ‘shadow’ over the United Nations

In the late 1990s, opponents on Manhattan’s East Side were able to delay the 72-story Trump World Tower, located across the street from the United Nations, but favorable court rulings and backing from construction unions and then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani ensured it got built.

Former CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite called the tower “a monstrosity,” but neighborhood groups and a host of wealthy New Yorkers, including conservative mega-donor David Koch, failed to stop it.

Even the U.N. secretary general, Kofi Annan, fretted the new tower would “cast a long, long shadow over everybody who lives in that neighborhood.” The tower opened in 2001.

Now, as president, Trump casts a different shadow over the U.N.

Return to sender

When Trump closed a 2013 deal to turn Washington DC’s majestic Old Post Office building into a hotel, he won good will by including a noted historic preservation architect, Arthur Cotton Moore, as part of his team. Moore had worked for more than 30 years to save the historic building.

“Arthur has a vision, a commitment, and an understanding of this building like no one else,” Ivanka Trump told Washingtonian magazine after he helped the Trumps win their bid.

But Moore left the project after work got under way, later noting, “I’m not given to a lot of chandeliers.”

Government documents later said Trump had violated his lease with the General Services Administration by covering the landmark’s century-old marble floors with carpet and concealing its historic wood and marble walls.

The Trump International Hotel Washington D.C. was ground zero for the MAGA faithful, high-rolling lobbyists and visiting dignitaries during Trump’s first term, earning tens of millions of dollars. Trump sold the hotel after he was voted out of office in 2020. It’s now a Waldorf Astoria.