On Friday, Oct. 24, the Axinn Center for the Humanities hosted the Middlebury Migration Conference in McCardell Bicentennial Hall as part of its “Migrant Justice in Vermont and Beyond” initiative. The event brought together a range of artists, advocates and academics to discuss their experiences and work around migration and migration justice. In a moment where ordinary migrant workers like Guadalupe and Emanual Diaz are kidnapped from South Burlington and transferred to detention centers across the country, the conference created a space for urgently needed mobilization and solidarity.

Throughout three panels interspersed with community networking time, participants and panelists interrogated the historical, current and future conceptions of migration. How do different narratives skew our social, political, and temporal perceptions of the process of migration, in Vermont and beyond? How can humanities research and its academic resources be more connected with on-the-ground action?

Elizabeth Camarillo Gutierrez, author of My Side of the River, describes how her parents’ self-deportation changed her family’s life.

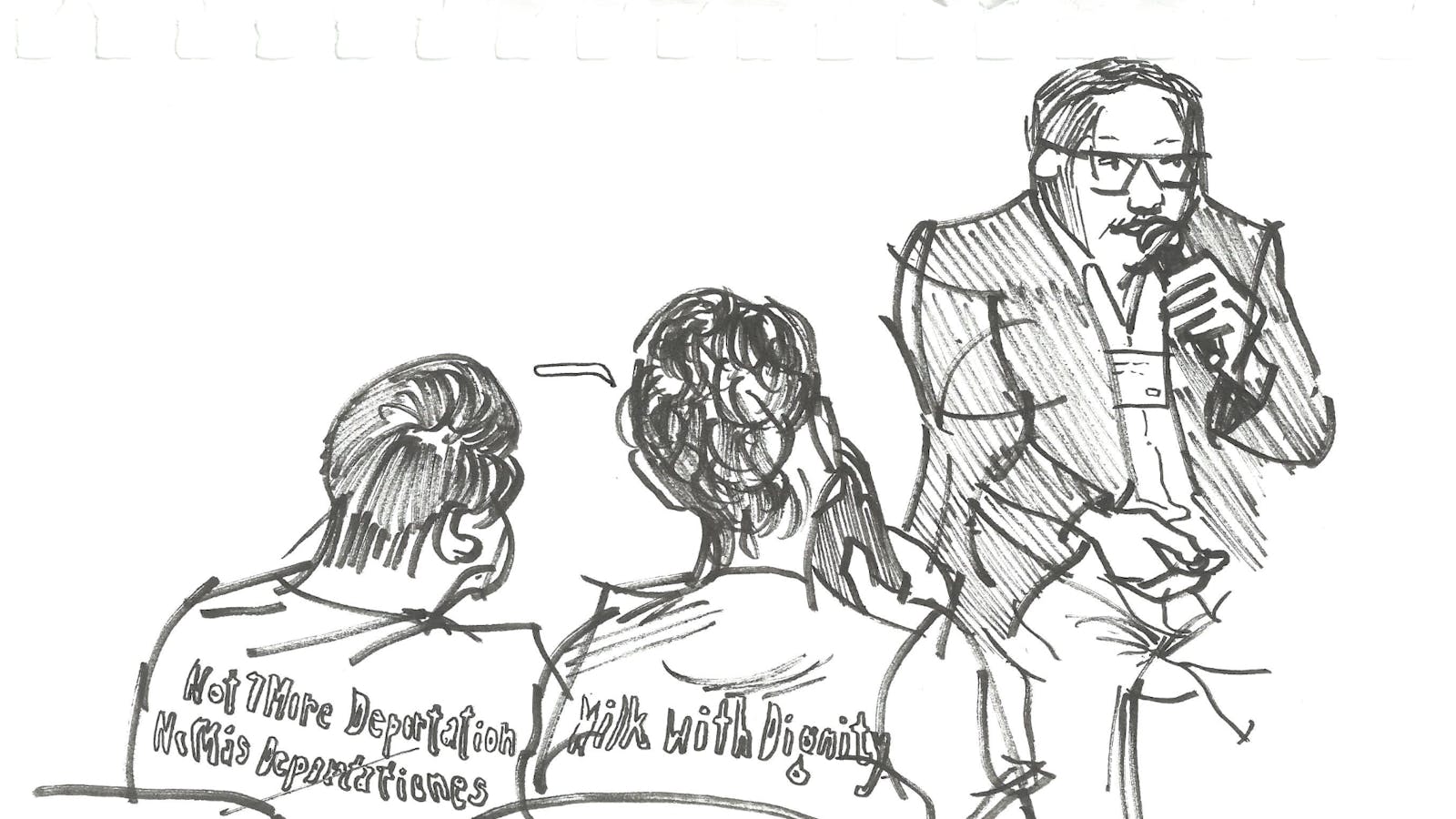

Migrant Justice leader and conference panelist Enrique “Kike” Balcazar underscored this necessary connection, emphasizing the importance of students in the movement for migrant justice.

“Students at Middlebury College, and in general, can contribute a lot to the fight for migrant justice. I hope that students leave the panels feeling inspired. Students have been very important to us for decades… having helped when there are protests and marches, transporting, translating, creating art, and more,” Balcazar told The Campus.

Catey Boyle, the two-year postdoctoral fellow of the “Migration Justice in Vermont and Beyond” grant, was inspired to design and create this conference after attending the Vermont Palestine Conference (VPC) in October 2024.

“The goal of the grant is also to be working on developing long-term, sustainable connections with community partners so that Middlebury is not just a college on a hill, but rather a college that’s within Vermont life, and particularly around Vermont migrant justice life,” Boyle said.

Fiori Berhane, professor of Anthropology at the University of Southern California describes the dire political conditions in Eritrea leading to people seeking migration.

Marita Canedo and Wafic Faour, two speakers Boyle saw at the VPC, became active members of the Middlebury Migration Conference. Marita Canedo is the Program Coordinator for the Migrant Justice Community Support Line and the Milk with Dignity Program, which organizes farmworkers, farmers, corporate buyers and consumers to secure dignified working conditions in dairy supply chains. On the third panel, Wafic Faour, member of Vermonters for Justice in Palestine and the Vermont Coalition for Palestinian Liberation, delivered calls to action to the Middlebury community.

Migrant Justice is an organization that models a symbiotic relationship between academia and community action. Since 2009, the organization has organized for economic justice and human rights for immigrant farm workers in Vermont. Organizer Enrique “Kike” Balcazar, previously targeted and detained by ICE for his leadership in activism, explained to The Campus that the organization is a part of a community advancing dignity and justice. In this network, Migrant Justice works with religious congregations, the Vermont Pride Center, the Vermont Worker Center, and student organizations like Juntos at Middlebury and University of Vermont (UVM).

The conference featured three panels: “Where I Come From,” “Passages,” and “Aftermaths.” Organized around a loosely “chronological” order, the different sections address the conditions that compel people to leave their homes, interrogate the difficulty and violence that characterizes physical migration, and ask what life is like as an immigrant living in Vermont. Together, three panels coalesce into a final question: what forms of solidarity and artistic creation have emerged in this final “chapter”?

Boyle explained to The Campus that the chronological structure of the conference is more than meets the eye. Even though inter-organizational solidarity in Vermont appears to be a concluding chapter to a linear progression of migration, the conference structure challenges this two-dimensional conception.

“The structure of the panels seems to be telling a story that’s going from point A to C. We were in a lot of conversations around this [during planning] because often ‘migration’ is not necessarily a story with a beginning, middle, and end. People are often displaced multiple times. People may not want to stay in Vermont long term,” Boyle said.

“Before every border is a world, a history, and a smell. Immigration starts with the memories and the things that are left behind,” panelist Elizabeth Camarillo Gutierrez said in her speech.

Student and faculty organizers, such as Victoria Fawcett ’25, and participants discuss and engage over Doña Alejandra Tacos.

Gutierrez is the author of the New York Times Editor’s Pick, My Side of the River. While her Mexican immigrant parents were forced to return to Mexico when she was 15, Gutierrez remained in the border town of Tucson, Arizona. She went on to become high school valedictorian, gain acceptance to the University of Pennsylvania, and live the life of a “super-immigrant,” a title that she rejects. She told the crowd that she was actually the “return on investment” for the true super-immigrants: Her undocumented parents who worked as custodians at a movie theater with an “unshakeable faith” in their American-born children. At the conference, she spoke in-depth about her experience growing up as a second generation American.

“Every story by my parents began with ‘cuando viviamos allá.’ Mexico was this imagined place, but [my brother and I] were still so Mexican in our identity… We really carried Mexico with us,” Gutierrez said to conference attendees.

As Boyle outlines, migration stories and their sights, sounds, and interweaving timelines do not align with bite-sized mainstream narratives. Gutierrez’s story fundamentally challenges mainstream conceptions of migration with memories that seem to defy temporal and physical boundaries. Living in a border town meant that she had access to intertwining cultures that are supposed to be separate. Blending Mexican heritage into her lived experience in America meant that the memory of places long left behind shaped her upbringing in real time.

Enjoy what you’re reading? Get content from The Middlebury Campus delivered to your inbox

“Every forced migration erases more than presence. It erases memory unless we fight to preserve it… [These are] more than just stories of displacement, but of the worlds that existed before and after it,” Gutierrez concluded.

Other panelists also challenged the audience to consider parts of migration stories that are often left out of mainstream narratives. Among them was KeruBo-Ogoti Webster, a Kenya-born, Winooski-based Afro-jazz vocalist, songwriter and storyteller who collaborates with the Alliance of Africans Living in Vermont to connect African migrants with local support such as legal, interpretation, and youth programming services. Webster emphasized the importance of understanding migrant experiences beyond the moment of arrival.

“[Ask] the deeper questions…what do these people deserve now that they are part of the fabric of Americans? When we are studying about [migrants], our focus is skewed because it is being led by someone with a broader agenda,” Webster said.

Faculty and student organizers and participants listened attentively in BiHall 216.

Fiori Berhane, panelist and professor of anthropology from the University of Southern California, expanded on the need to examine the historical dimensions of migration. She spoke to conference-goers about migrations out of the East-African country of Eritrea, the first Italian colony and most-militarized country in the world. Using primary source interviews, Berhane read out conversations conducted with Eritrean migrants.

“In a talk like today’s where there’s migrant activists, students and the general public, I’m trying to get at a basic sketch of what’s going on, of memories of home… I want to center the voices of the people that I work with… For a general public that is much more important than the theoretical insights that I would share with other anthropologists or academics,” Berhane said in an interview with The Campus.

The conference was grounded in its effort to turn these conversations into activism. Keeping these discussion themes at the forefront, the combination of panelists, students, and organizers, reconciled the role of academia and activism.

Connecting academia with action, the event concluded with a “Community Open House” in which the following organizations tabled and fundraised: Migrant Justice at Middlebury, Middlebury Students for Justice in Palestine, Vermont Coalition for Palestinian Liberation, Vermont Folklife, Clemons Family Farm, the Vermont Afghan Alliance, Art Lords, the Alliance of Africans Living in Vermont, Open Door Clinic, FreeHer Vermont and the Henry Sheldon Museum.

Victoria Fawcett ’26, a student on the steering committee for the conference and a Spanish-to-English medical translator at the Open Door Clinic, commented on how the college’s connection to migration justice issues is often overlooked.

“We go to the dining hall, we drink the milk, we eat the yogurt, but we forget about who the people are organizing the cows, producing the milk, and providing it, and honestly, risking their lives every day to do that,” Fawcett said.

Supporting the Milk with Dignity campaign, as shared by Balcazar and Canedo, is one concrete way in which Middlebury students can join the fight for migrant justice in our community. Check out www.migrantjustice.net to help push the national grocery chains like Hannafords to join this program overseen by the Milk with Dignity Standards Council for dignified working conditions for our migrant neighbors.

June Su

June Su ’27 (he/him) is the Senior Multimedia Editor.

June is a political science major and studio art minor, also studying history and Spanish. He spent the summer of 2025 working as a political science research assistant examining investments in the Congo River Basin to achieve international biodiversity and carbon goals.