Wesley Cheek is a sociologist of disasters and an assistant professor of emergency management at Massachusetts Maritime Academy. His research focuses on community involvement in post-disaster reconstruction, especially following the 3.11 Triple Disaster in Japan. You can find him on Bluesky @wesinjapan.

In 2018, while heroic former Royal Thai Navy SEAL diver Saman Kunan was drowning inside of a cave system in Chiang Rai trying to rescue twelve scared young boys and their soccer coach, billionaire gadfly Elon Musk was busy dropping off an unusable minisub. Musk, who wandered around the rescue camp briefly and then flew back home, would later call Vernon Unsworth, the first experienced cave explorer on the scene and later recipient of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal for his efforts, “a pedo guy”.

Musk managed to parlay this disastrous ineptitude into being granted the reins of the federal budget when President Trump returned to power in 2025 as the head of the “Department of Government Efficiency” or DOGE. Musk’s dismissive and conspiratorial views towards The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) aligned with the Trump Administration’s disdain for the administrative state, dislike of foreign aid, and contempt for competent expertise.

As we watched Hurricane Melissa, one of the strongest Atlantic hurricanes on record, make landfall in Jamaica, disaster professionals were left wondering what capacity the United States has to respond to this and other disasters.

From Bretton Woods

USAID emerged from the post-World War Two need to rebuild massive sections of Europe, as well as the capitalist demand to beat back communism, which had managed to beat back the tide of fascism. The emergence of both neoliberalism and international post-disaster reconstruction are fundamentally linked to this period following World War II, and the planning for how to manage its aftermath. The close of the war created the opportunity to set a new global order, part of which involved establishing international development as a mechanism to address global economic inequality. Simultaneously, the international community began to treat major catastrophes, including post-war reconstruction, as crises that required a coordinated global response. That was the role of the Marshall Plan, to rebuild Europe, yes, but also to offer a robustly engaged United States as a viable alternative to Soviet communism.

This new framework for reconstruction, which separates the modern approach from previous historical methods, was formally established at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference. The Allied Nations sought to prevent future conflicts, which they believed were partly caused by the poorly handled aftermath of World War I, by focusing on a two-pronged strategy: stabilizing global financial markets and undertaking the physical reconstruction of war-torn countries. This led to the creation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to ensure financial stability, and the World Bank to manage reconstruction and development. This model is rooted in the belief that engagement with a globalized, urbanized economy would be the primary stabilizing force, and it continues to be the dominant paradigm for international post-disaster recovery today.

This intertwined relationship meant that as the Global North adopted neoliberalism as its dominant policy and ideology, it also became the prevailing framework for both international development and post-disaster reconstruction efforts. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) was born out of this milieu in 1961. Of course there are many issues of colonialism, imperialism, and global inequality wrapped up in the entire enterprise, alongside its nobler and more humanitarian impulses. That paternalistic origin and often enduring institutional perspective is a valid and constant criticism of the development world in general and USAID in particular. It is also worth noting that USAID has frequently, and not entirely blamelessly, been singled out as a CIA cutout. Nevertheless, over the years USAID’s disaster response and relief efforts have been laudable.

Managing Through Disaster

Development, and through the development framework disaster response and relief, became a tool of soft power by which the two superpowers interacted with the Third World during the Cold War. The 1986 earthquake in El Salvador and the 19881 earthquake in Armenia, both of which occurred in complex political situations, motivated the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance to establish Disaster Assistance Response Teams (DART) under USAID. The after-action review following the December 1988 Armenia earthquake response highlighted several lessons learned. The most crucial of these was the realization that the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) needed to respond with an established organizational structure where all responders were trained in and understood their specific roles and responsibilities.

These DART teams were heavily influenced by the U.S. Forest Service’s Incident Command System (ICS). In the event of a disaster, USAID could stand up a Response Management Team (RMT). The DART was beta tested during Hurricane Hugo in September/October 1989. The team, with Paul Bell serving as team leader, was operating out of St. John’s, Antigua. The first official—though not quite ready for prime time—DART deployment took place in Northern Iraq in 1991. This is when non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other nations first learned the term “DART” and realized that the team had an accessible budget to use for response efforts. USAID DARTs were active from the 1990s into the 2020s, with one stood up as recently as 2023 to help with refugees in Armenia.

Three major disasters over the last two decades provide a window on USAID’s capability: the 2010 Haiti Earthquake, the Earthquake/Tsunami/Reactor Meltdown “Triple Disaster” that hit northern Japan on March 11th, 2011, and the response to the 2015 Nepal Earthquake.

On 12 January 2010, a magnitude 7 earthquake struck Haiti, centered just a short distance away from Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince. By the 13th, USAID DART teams were activated and USAR teams were in action on the 14th, doing urban search and rescue (USAR), logistics, rapid building assessments, and air transport. When the Tōhoku earthquake struck 45 miles off the coast of Japan, it provoked a massive tsunami, whose massive waters in turn flooded backup systems at some of the reactors of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant. In response to the triple disaster,USAID deployed a heavy DART team including nuclear radiation experts and USAR teams the day after the event. The team remained deployed for two months. Hours after the April 2015 Nepal Earthquake, USAID mobilized a 148 person DART team with USAR personnel out of Los Angeles and Fairfax, Virginia. Their RMT also put together logistical assistance, Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) education, and capacity building support from nuclear meltdown mitigation to conflict medicine.

As Trump came into office there were still USAID staff deployed in Gaza. Three staff members were sent to Myanmar to respond to the earthquake in March of 2025, however they were fired once they arrived in the country.

Into the Woodchipper

Despite this history, Musk was possessed with a belief that USAID was “a viper’s nest of radical-left Marxists who hate America” and imploded the agency and replaced it with, well, nothing really. As Moynihan and Zuppke have suggested, Musk couldn’t understand, or at least acted as if he couldn’t understand, basic numeracy and proposed that USAID spending 10% of its budget on direct payments to local organizations must thereby mean that the other 90% went to shady or frivolous nonsense. (See Bonnifield and Sandefeur for an actual breakdown).

When Elon Musk took over the government in early 2025 he tweeted “We spent the weekend feeding USAID into the wood chipper. Could gone to some great parties. Did that instead.” There is no reason that we should not take Musk at his word. Decades of disaster response and recovery are now gone. However, Musk and the Trump Administration cannot erase the legacy of USAID’s international disaster relief.

It is hard to say much definitively on the United States’ potential response to any disaster overseas as no one in the profession, as far as I know, has any real clue about what the actual plans are. That in and of itself is a tremendous problem. Disasters will not wait around while we try and sort things out. It is the United States leadership on disasters that has been thrown in the woodchipper.

Rebuilding from the Splinters

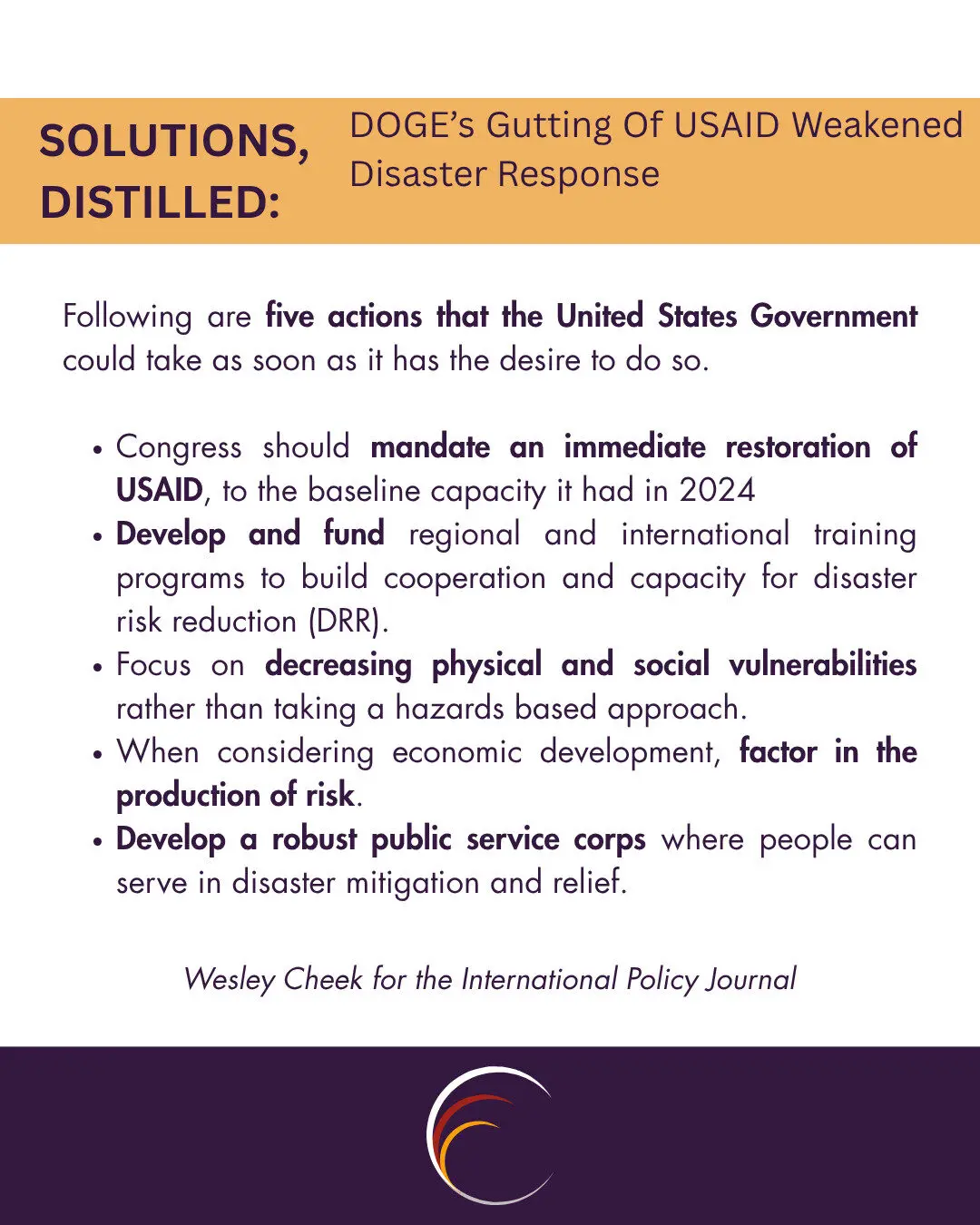

All is not hopeless. Every disaster provides a chance to rebuild. If we view the current state of the United States capacity to respond internationally to disasters as a catastrophe, we can also see that it provides us with somewhat of a blank slate. So, to be hopeful, what can we do if the U.S. wants to become an actual leader on the world stage?

Most immediately, the US could restore the previous system, through rehiring, new recruitment, and new protections against future DOGE-like destruction. This would help staunch the loss of specific technical expertise, though by necessity some of that would have to be retrained.

Beyond that baseline, the US could do so much more. To start, the US international development community should move away from viewing the Global South as a subordinate underclass that simply needs more economic development. While certain types of economic development can alleviate vulnerabilities, an ideological commitment to economic development as such does little but construct risk through furthering inequality. For too long the United States has taken a hazards based approach, or a focus on things like fires, earthquakes, hurricanes, and tornadoes. Instead, the US should invest in efforts that try to alleviate the underlying vulnerabilities that make people susceptible to disasters. Disaster researchers have shown that things like wealth inequality, systematic racism, and gender inequality make disasters worse. We can improve outcomes by addressing these vulnerabilities. Part of moving away from the current paradigm would include developing and funding international training programs in disaster risk reduction (DRR) that would create cooperation and build capacity. This can be at the regional and international level.

There is a great desire amongst many people to work on preventing and responding to disasters. The United States could, and should, create a robust public service program that works on disaster mitigation during blue sky situations and responds to disasters when need be. People want to help each other, and one of the greatest things our country could do is enable that type of pro-social behavior. People have the desire to respond to disasters with solidarity and compassion. A restored disaster response capability could give them the means with which to do so.

1 Former USAID/BHA staff. Also see: Olson, Richard Stuart. “The Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID): A Critical Juncture Analysis, 1964–2003.” Macfadden & Associates (2005): 1-52.