Lauren Gilbert argues that migrants to the UK are net fiscal contributors, adding much more to the economy than they take out, and that the recent collapse in immigration will harm the UK’s economic prospects.

Across the political spectrum, politicians are concerned about the fiscal impact of immigration. The concern has been most pointed from Reform, who have warned of a coming ‘fiscal abyss’ if recent immigrants are not forced to leave the country, but it is not limited to them.

Tory rising star Katie Lam argued that new immigrants will cost the Treasury “hundreds of billions of pounds” if they stay in the UK. Douglas Carswell has said that ‘migrants are draining our welfare system’. Even Labour has picked up the rhetoric, with the Home Secretary saying that fiscal contribution is “a condition of staying in the UK”.

All of this concern is misplaced. Home Office data suggests that recent immigrants are more likely to be working than British nationals and make higher wages than them. They are also likely to be net fiscal contributors. Far from draining our welfare system, migrants are supporting the British state’s solvency.

My analysis is based on Home Office salary data for the fiscal year 2023-2024. They provide earnings and labour force participation data for migrants who first entered the UK between 2019 and 2023. This dataset includes some 1.7 million people who entered on visas that permit work. This dataset excludes students – who are not expected to be in work – but includes all other types of visas, including humanitarian visas.

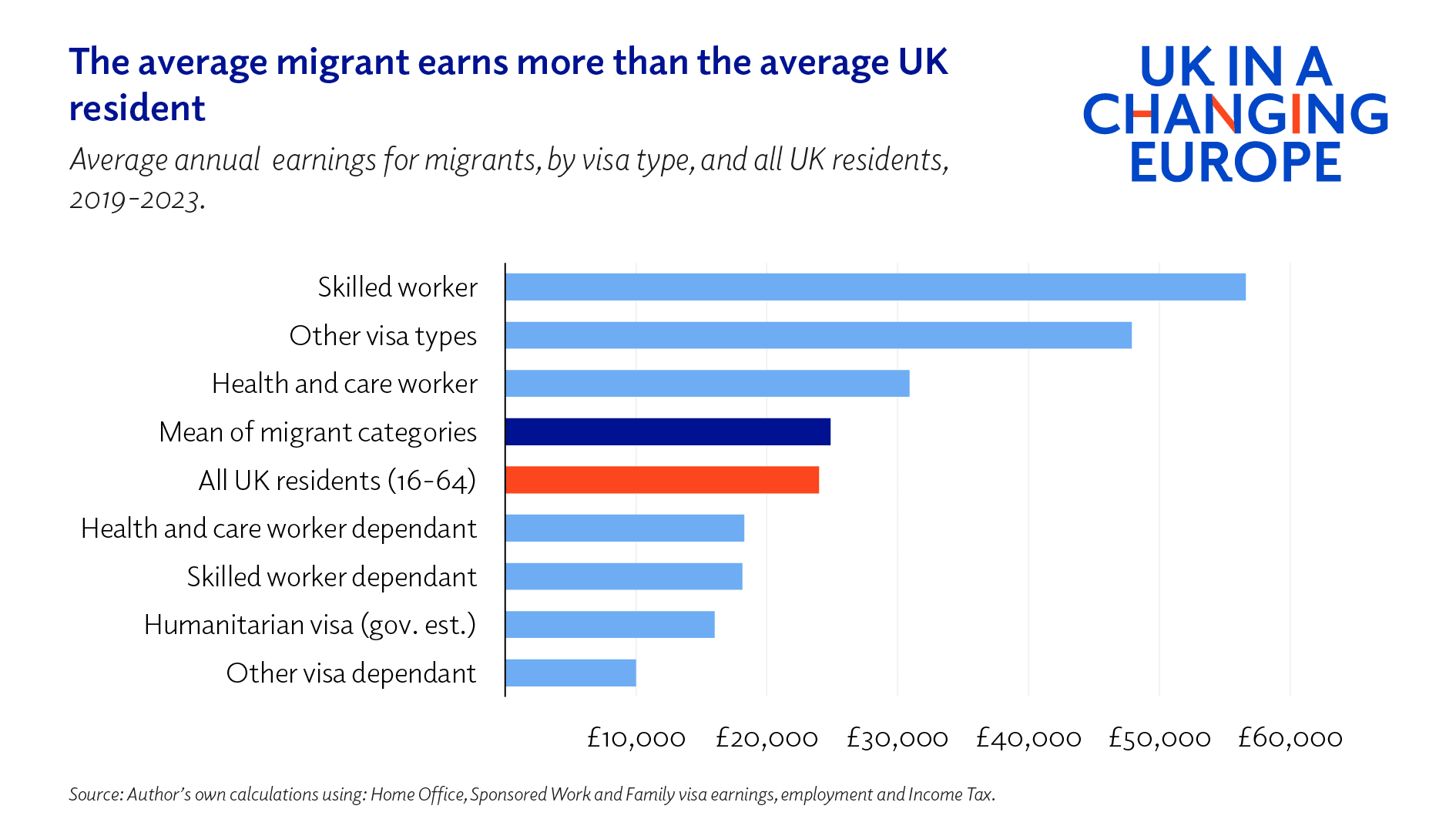

Contrary to the belief that these migrants work in low-wage, casual positions, I find that the average migrant actually makes more than the average native-born person aged 16-64. I calculate that the mean annualised wage of a migrant who entered in this period was £24,881, while the average person in the UK only made £23,990 that year.

Note that these figures include dependants and those currently not in work, but not those who have (very likely) left the country. The mean wage for an employed migrant is some £33,534 per annum, well above the minimum wage and the London Living wage. This, again, is more than the average wage for a native-born person; the overall average wage brought home by an employed person in the UK was just £31,891.

But it is not simply that employed migrants support unemployed family members. Despite the common perception that migrants “didn’t come here to work”, labour force participation for non-UK citizens is actually higher for migrants than it is for British citizens. This makes sense; since many migrants are not allowed to access public benefits, and some are on visas that require employment, it will be true by construction that migrants are very likely to be working.

There are two reasons to believe the wage gap between migrants and the native-born will grow over time, with migrants continuing to outearn natives.

First, migrants are, on average, younger than the native-born; they can expect their wages to increase as they gain experience. The Migration Observatory also has found that migrants’ wages rise very sharply over their first few years in the UK – as people gain UK experience and knowledge, they are able to find better jobs.

Secondly, it is likely that those who stay long-term earn more than the average immigrant. In general, when immigrants struggle in a new labour market, they are more likely to return to their home country. In the Netherlands, the likelihood of staying was an inverted U shape – the lowest earners were the most likely to leave, followed by the highest earners, with medium-earners the most likely to stay.

All of this is good news for the public purse. Indeed, Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) modelling suggests that the UK will benefit significantly from the recent increase in migration.

In general, people are costly to the state during two periods of their life: childhood and old age. In childhood, the state must fund care and schooling; in old age, the state must provide care and pay for medical expenses. Immigrants are a bargain for the British state because it need not pay for their early childhood and education.

The OBR models that a migrant that makes a similar amount to the average Briton will contribute nearly £500,000 more in taxes than they receive in benefits. Given the average recent migrant makes slightly more than the average British person, they will be a significant net fiscal contributor.

Nor would their children be particularly costly to the British state. It is true that immigrants tend to have more children than average, but the children of immigrants tend to earn slightly more than the children of the native-born. Perhaps one might be concerned about the long-run fiscal outlook of the British state in general, but there is no evidence that the children of immigrants will make the situation worse.

Indeed, there is simply no sign of a fiscal catastrophe from the “Boriswave” – i.e. surge in net migration over the past few years. Recent migrants are very likely to be employed, paying tax and seem to be contributing to British society. The Boriswave will help, rather than hurt, Britain’s fiscal position.

Furthermore, this would seem to suggest that the recent collapse in immigration will harm Britain’s finances. The OBR believes that low net migration could Britain’s GDP per capita growth by about 1.5 percentage points by 2028-2029. In real terms, this would mean that Britain would be about £700 worse off per capita.

This may well be good politics – in early 2025, two in three Britons thought immigration was too high – but it is very likely to be bad economics. Most immigrants are already net fiscal contributors; decreasing their numbers will only decrease their contributions.

By Lauren Gilbert, a researcher in innovation, science, global health and global development.