As in the previous update, the number of new entries added over the past two weeks is almost double our typical figure. This spike is largely due to the inclusion of people who were previously listed as missing in action, whose deaths have now been confirmed.

The recent rise in recorded fatalities is not primarily the result of the present situation at the front, which we observe with delay, but rather reflects losses that occurred in earlier months and years.

In this update we focus on volunteers, and in particular on the youngest people taking part in the war. Volunteers continue to be, as before, the principal manpower sustaining the conflict at its current stage.

The Russian authorities have taken deliberate steps to broaden their capacity to recruit personnel on contract to the armed forces. For example, the State Duma enacted an amendment to the law “On Military Duty and Military Service” and related statutes that allows people without citizenship to sign military contracts. According to estimates from Memorial, the human rights organisation, there are roughly 100,000 such stateless people in Russia.

Lawmakers also adopted measures designed to bring the very youngest recruits into the army: not only those aged 18, but people who become adults literally on the day they sign their contract.

Under the pre-war version of the law, a person could sign a contract only if they met at least one of the following conditions: they had completed three months of compulsory conscription service, or they had begun conscription having already obtained a vocational (middle-special) or higher education, or they were in the reserve (that is, they had already served conscription), or they hadn’t served but already held a vocational or higher qualification.

Taken together, these rules made it effectively impossible to sign a contract immediately after turning 18. It is rare for someone to be called up straightaway on their 18th birthday; most school-leavers do not yet have the required educational qualifications; and the three-month minimum period of conscription had to be served before a contract could be offered.

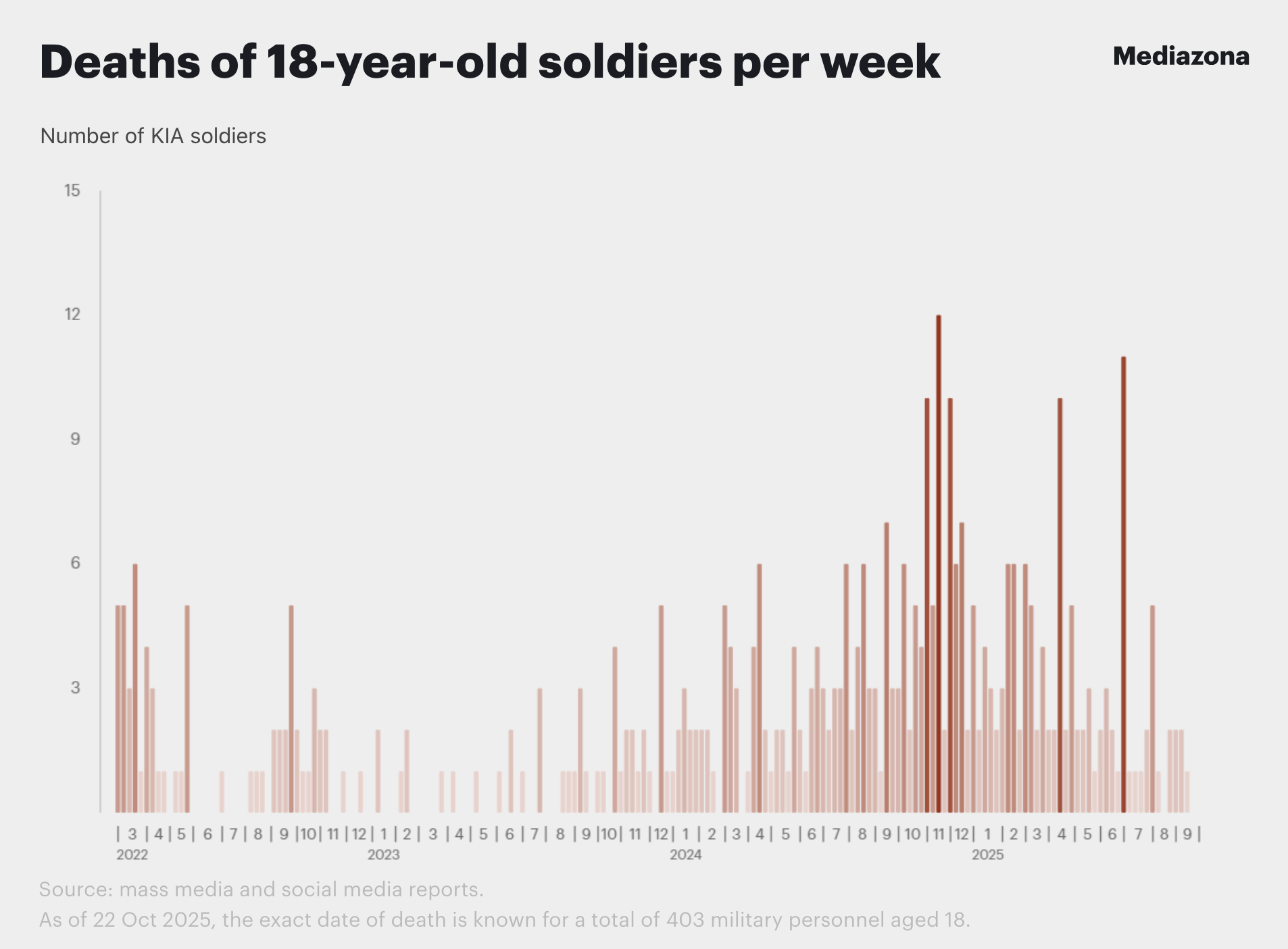

All of these restrictions were removed by amendments that took effect on April 14, 2023. At the time, however, the change did not produce a sudden surge in the number of 18-year-olds killed. It may have simply given officers more opportunity to persuade conscripts to sign contracts during their term of service, without immediately sending them to the front.

The situation changed profoundly due to a separate legal amendment: from October 2024 the Russian army was permitted to recruit people at any stage of criminal proceedings, including while a person is still under investigation or on trial. From that moment we observed a sharp rise in the number of teenagers killed at the front. Individual obituaries suggest a common pattern for these recruits, comparable to other assault troops: from recruitment to death often elapses only one to two months.

These short case notes are drawn from our database to illustrate how young recruits are reaching the front.

Maxim Nasilovsky, who was 18 years and one month old at his death, is presently the youngest confirmed soldier in our records. He had been convicted, at 17, of killing his mother and sentenced to five and a half years in a penal colony. He appears to have been recruited while still in pre-trial detention, and died shortly after his 18th birthday. Official paperwork contains contradictory entries about the circumstances of his death (one document records that he died in the line of duty, another that he did not); our anonymous source insists that he committed suicide, no independent investigation has been made public. Ilya Vasilyev, born August 2007 and from Zvenigovo in the Mari El Republic, moved to Yoshkar-Ola to study at a construction college. He took an academic leave and signed a contract; he was killed in October 2025, at 18 years and two months.Tsivan Ayurzhanayev, from Buryatia, came to public attention as a teenager who ran a small family farm. At 18, he enrolled at a college in Novosibirsk and appears to have been recruited in Ulyanovsk region in June 2025. He went missing less than a month later. What we know about losses

What we know about losses

The map below shows the distribution of casualties across Russia’s regions. These are absolute figures and have not been adjusted for population or number of military units.

You can filter the map to show total losses, losses by branch of service, or the home regions of mobilised soldiers who were killed.

In most cases, official reports or visual cues like uniforms and insignia allow us to determine a soldier’s branch of service, or how he came to be in the army (mobilised, volunteer, prisoner, etc.).

The chart below compares these different groups of servicemen.

From early summer and into the mid-fall season of 2022, volunteers bore the brunt of the losses, which is strikingly different from the situation in the initial stage of the war: in winter and early spring, the Airborne Forces suffered the greatest damage, followed by the Motorised Rifle troops.

By the end of 2022 and the beginning of the next year, losses among prisoners recruited into the Wagner PMC increased markedly. They were formed into “assault groups” to overwhelm Ukrainian positions near Bakhmut.

By March 2023, prisoners became the largest category of war losses. After the capture of Bakhmut, there have been no cases of mass use of prisoners so far.

By September 2024, volunteers once again emerged as the largest category among the KIA. This shift reflects a cumulative effect: prison recruitment had significantly waned, no new mobilisation had been announced, yet the stream of volunteers continued unabated.

By November 7, 2025, the death of 5,943 officers of the Russian army and other security agencies had been confirmed.

The proportion of officer deaths among overall casualties has steadily declined since the conflict began. In the early stages, when professional contract soldiers formed the main invasion force, officers accounted for up to 10% of fatalities. By November 2024, this figure had dropped to between 2–3%—a shift that reflects both evolving combat tactics and the intensive recruitment of volunteer infantry, who suffer casualty rates many times higher than their commanding officers.

Officers killed in Ukraine

To date, the deaths of 12 Russian generals have been officially confirmed: three Lieutenant Generals, seven Major Generals, and two who had retired from active service.

Lieutenant General Oleg Tsokov, deputy commander of the Southern Military District, was killed in July 2023. In December 2024, Lieutenant General Igor Kirillov, head of the Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical (NBC) Protection Troops, was killed by a bomb in Moscow. Lieutenant General Yaroslav Moskalik, a senior officer in the General Staff’s Main Operational Directorate, was killed by a car bomb in a Moscow suburb in April 2025.

Two deputy army commanders, Major General Andrei Sukhovetsky (41st Army) and Major General Vladimir Frolov (8th Army), were killed in the first weeks of the war. In June 2022, Major General Roman Kutuzov was killed in an attack on a troop formation.

Major General Sergei Goryachev, chief of staff of the 35th Combined Arms Army, was killed in June 2023 while commanding forces against the Ukrainian counter-offensive in the Zaporizhzhia region. In November 2023, Major General Vladimir Zavadsky, deputy commander of the 14th Army Corps, was killed near the village of Krynky.

In November 2024, Major General Pavel Klimenko, commander of the 5th Separate Motorised Rifle Brigade (formerly the “Oplot” Brigade of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic), was fatally wounded by an FPV drone.

In July 2025, a strike on the headquarters of the 155th Naval Infantry Brigade killed at least six officers, including the Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Navy, Mikhail Gudkov.

The two retired generals on the list are Kanamat Botashev, a pilot who had been dismissed for crashing a fighter jet and was fighting for Wagner PMC when his Su-25 was shot down in May 2022, and Andrei Golovatsky, a former Interior Ministry general serving an 8.5-year prison sentence who was killed in June 2024.

The date of death is known in over 113,300 cases. While this data does not capture the full daily reality of the war, it does suggest which periods saw the most intense fighting.

Please note that the data of the last few weeks is the most incomplete and may change significantly in the future.

The age of the deceased is mentioned in 125,000 reports. For the first six months of the war, when the fighting was done by the regular army, the 21-23 age group accounted for the most deaths.

Volunteers and mobilised men are significantly older: people voluntarily go to war over 30, and the mobilised are generally over 25.

Our methods

Mediazona and a team of volunteers continue to study posts on social networks, reports in regional media, and publications on government websites.

Our criteria for confirming a death are stringent. We require a publication in an official Russian source or media outlet; a post by a relative (which can be verified by matching surnames or other details); posts in other sources, such as community groups, if they are accompanied by a photograph of the deceased or specify a date for a funeral; or photographs from cemeteries.

We do not include military losses from the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics (DPR and LPR). However, a Russian citizen who voluntarily joined the armies of these entities, or was sent there after mobilisation, is included in our count.

We determine the branch of service from reports about where the deceased served, or by their insignia and uniform, not by their military specialty. For instance, if a soldier operated a self-propelled gun within an Airborne Forces (VDV) unit, we classify him as VDV, not as artillery.

In the infographic, we classified FSB, FSO, Air Defence, NBC Protection troops, signal corps, and Air Force Ground Services as “other troops.”

We continue to collect data on deceased servicemen. If you see such reports, please send links to them to our Telegram bot: @add24bot. Instructions for contacting Mediazona (anonymously if needed) can be found here.