(eric1513/Getty Images)

In 2013, Cap-and-Trade was launched to help meet California’s goal of drastically cutting down on greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. It’s now been 12 years, the program has a new name and environmental justice groups still don’t believe the program is doing enough to protect Californians or even getting us that much closer to the emissions goal.

Previously known as Cap-and-Trade, the recently reauthorized (and renamed) Cap-and-Invest program is meant to tax high-polluting industries and reinvest that money back into communities while simultaneously reducing the state’s emissions.

“The program is not gonna get us to 2030, much less to 2045 and I think everybody’s kind of starting to realize that,” said Katie Valenzuela, a consultant and lobbyist for environmental groups.

Cap-and-Invest works by setting a statewide cap on greenhouse gas emissions from industrial sectors, including oil and gas extraction/refining, power generation and manufacturing. These industries are required to purchase “emissions allowances,” essentially giving them permission to pollute a certain amount. One allowance represents one metric ton of CO2.

The money generated from those allowances then gets reinvested into other climate programs and communities across the state. The idea is that each year, both the cap and the allowances will decline, inching the state closer to its ultimate goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

While good in theory, environmentalists say the program has not done enough to effectively address and serve the communities most impacted by these industries and their pollution. The facilities that are regulated through Cap-and-Invest are three times more likely to be built in or around low-income communities of color, according to a report by the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment.

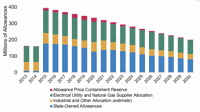

California Cap-and-Invest program allowance budgets. (Courtesy of the California Air Resources Board)

The pollution problem

Valenzuela, who helped lead a coalition of environmental groups involved in lobbying for the reauthorization, said the likelihood of the facilities being built near marginalized communities isn’t shocking.

“Those are the communities with the least power, those are the ones with the least income, the least ability to kind of push back on these things,” she said. “So that part wasn’t surprising. The part that was really frustrating for us was that as Cap-and-Trade progressed, the companies were more likely to use offset credits to meet their obligation, rather than reduce emissions at the source.”

Since the program launched, statewide greenhouse gas emissions have gone down and air quality has generally improved, seemingly pointing to a successful program.

“With that said, there is still an equity gap in air quality throughout the state where we still see that the quality of the air quality in Black and Brown neighborhoods, continues to be much worse than the air quality in White neighborhoods,” said Lolly Lim, senior program manager for climate equity at the Greenlining Institute, a nonprofit policy advocacy group dedicated to climate justice. “So while across the state, things are getting better, we’re still seeing these localized disparities perpetuated.”

The most common negative impacts of living near these high-emissions facilities include asthma, cardiovascular disease, reduced lung function and premature death, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

The Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment report also shows that since the program started, the majority (68%) of health benefits from reductions in emissions have been for people of color.

Despite the benefits that have been seen in the last 12 years, the program at its core still allows for a certain amount of “reasonable” emissions, in part so these industries don’t up and leave California altogether due to environmental restraints, according to Lim.

“The idea was always to ramp down those allowances over time,” said Lim, “but that didn’t happen.”

What’s in (and not in) the program?

A last-minute deal between Governor Gavin Newsom, Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas and Senate President Pro Tem Mike McGuire resulted in a few key updates to the program, which was reauthorized through 2045:

AB 1207 reauthorizes the program and changes how the California Air Resources Board (CARB) distributes these allowances (pollution permits) to the various industries.

SB 840 details how the state will spend revenue from the program. Starting in 2026, $1 billion will be allocated to high-speed rail and $1 billion will go to lawmakers to direct through the budget. The program will also continue to fund housing, transit, clean-air programs, wildfire prevention and safe drinking water.

CARB will need to submit a transparency study next year

Consumers will continue to benefit from the program in the form of a twice-yearly climate credit, which gives breaks on utility bills during times when prices are highest.

While some of the changes to the program were supported by environmental groups, the reauthorized program ultimately fell short, said Valenzuela.

A crucial point missing from the reauthorization is a tangible and enforceable way to “address air quality in the most eluded places throughout the state,” said Lim.

The coalition was asking for the reauthorization to include provisions that would strengthen the enforceability of CARB to set more direct emissions control measures, as well as phase out allowances for oil and gas. These provisions would build on AB 617, a bill passed in 2017 during the first reauthorization of the program.

Although AB 1207 was a better deal than was previously on the table, the coalition ultimately opposed the reauthorization package “because they failed to live up to the AB 617 promise that they made, and they cut our bill down,” said Valenzuela.

The reauthorized program still does not close loopholes that allow certain sectors to bypass the ultimate goal: cutting down on emissions at the source. With the way the program is set up, industries can simply buy the credits and meet the obligations of the program while not addressing the root of the problem, argued Valenzuela.

“(Cap-and-Invest) isn’t made to phase out sectors, it’s made to give sectors a way to comply with the law, and those are two different things,” said Valenzuela. “So, if we’re really serious about meeting these climate goals, there’s still a lot of tough discussion ahead of us and communities that have been most impacted and historically born that brunt deserve to have more of a voice in how that happens.”