As strategic tension is escalating in East Asia, policymakers often tend to select modern examples—the Cold War or other contemporary conflicts like the 2022 Russia-Ukraine War—to examine historical similarities. Yet interestingly, one of the most indicative cases that offers notable implications to the Korean Peninsula originates from the relatively remote past; namely the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War. Despite the time gap between the 19th century and the present day, the crucial elements that comprise the war—political dynamics, fragility of alliances, and probability of miscalculation—provide strikingly relevant warnings to the current Korean Peninsula.

The Franco-Prussian War emerged not from structured necessity but from diplomatic manipulation, nationalistic honor, and exploitation of intelligence. Prussia’s prime minister Otto von Bismarck carefully designed a situation in which France had to respond, still suffering from the declining national prestige under Napoleon III. Bismarck’s intentional editing of the ‘Ems Dispatch’ cornered France to a point where backing down was considered utterly unacceptable. As a result, the war that widely predicted France’s quick victory turned into a devastating defeat, preparing a deeply unstable stage—by reshaping the political landscape of Europe for the next couple of decades—that led to WWI.

Such structural dynamics—the trap of prestige, the illusion of a short war, alliance fragmentation, and destabilization of post-war settlement—have urgent relevance to modern-day two Koreas.

Manufactured Crisis and an Illusion of a Controlled War

The first and the most enduring lesson of 1870 is the risk of believing that war can be either controlled, limited, or decisive. Both France and Prussia expected a rapid military campaign that would bring a clear winner and manageable political consequences. However, in actuality, this conflict caused domestic turmoil, regime collapse, and long-term geopolitical impact.

Similar illusion persists on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea might imagine that through various measures—launching multiple missile salvos, concentrated artillery bombardment, SOF penetration, and nuclear blackmail, or a combination of some of them—it could coerce Seoul into an early political settlement. Meanwhile, from some US and South Korean quarters, the possibility of a swift ‘decapitation operation’ or early decisive blows has been discussed. Yet such types of assumptions could help escalate the risk of war due to actors’ belief that they could easily achieve rapid victory.

The Franco-Prussian War also underscored that a symbolic dispute could evolve into an actual conflict. As the Ems Dispatch transformed diplomatic misunderstanding into a casus belli, present-day South Korea is vulnerable to incidents that could dent national prestige—disclosed records of hotline conversations, manipulated voice files, and edited video of maritime dispute—amplified by digital technology.

In a political environment where face-saving and public disgrace still function as strong factors, such events could accelerate escalation before leaders sort out measures for damage control.

Alliance Fragility and the Risk of Strategic Isolation

The second major lesson pertains to alliance dynamics. In 1870, France entered the war in a completely isolated condition. Austria was recovering from its defeat by Prussia four years earlier, Russia was indifferent, while Italy had almost no incentives for intervention. Bismarck made sure that France had to fight alone if war occurred.

South Korea should avoid such a similar fate in whatever type of future crisis. In particular, when a dual contingency erupts in the Taiwan Strait and in the Korean Peninsula, or a large-scale war breaks out in Europe, US resources and attention could be stretched thin, which would raise the uncertainty of US military intervention in the early phase of the Korean contingency. Likewise, Japan would have to prioritize its homeland defense when faced by a direct missile threat. Other middle powers would consider the Korean Peninsula as a secondary issue if a clear coordination mechanism does not exist.

For this reason, deeper institutionalization of US–Japan–South Korea cooperation is a necessity. Joint operation plans, integrated intelligence architecture, and missile defense coordination are not a mere symbolic gesture but a reinforced structure that makes isolation next to impossible. Expansion of partnership to Canada, Australia, UK, Europe, and ASEAN member states also lowers the chance of Seoul encountering a major crisis under limited external assistance. The lessons from 1870 are clear; isolation is catastrophic even when unintended.

To Avoid Post-War Settlement that Creates Future Instability

The last crucial lesson of the Franco-Prussian War is on peace, politics, and ending the war. Although Prussia’s annexation of Alsace-Lorraine was a tactical victory, it engendered France’s continuous sentiment for revenge. Such an attribute resulted in an unstable European order for the following decades and became a precursor to WWI.

If applied to the Korean Peninsula, it contains grave implications. In whatever situation that includes the implosion of the North Korean regime or Pyongyang’s military defeat, a punitive or victor-oriented post-war settlement would likely lead to ceaseless anger, revolt, or political division within North Korea. By eliminating the entire elite without any conditional path to integration, erasing local identity, and forcing a rapid restructuration of pre-existing institutions, South Korea could create a South Korean version of Alsace-Lorraine; this could emerge as a long-term grievance that hampers stabilization and genuine unification.

To avoid such an outcome, South Korea needs a realistic war-ending framework that distinguishes between limited and ideal objectives. Moreover, it requires careful planning on post-war administration, transitional justice, mechanisms for conditional pardon, and an integration strategy that values reconstruction over vengeance. South Korea’s internal political resilience is equally important. Massive conflict could pressure political institutions, and internal conflict could weaken South Korea unless there is a pre-designed bipartisan plan.

Conclusion: Strategic History for a Strategic Peninsula

In the sense that the most dangerous military conflict is the one that states firmly believe they could sufficiently control in the process as well as the outcome, the Franco-Prussian War provides a profound lesson. France went to war with its confidence in military and diplomatic instincts, while Prussia believed that it mastered escalation and political manipulation. Nevertheless, both sides were wrong. The end result echoed far beyond the initial calculation.

Where nuclear dynamics, compressed escalation timeline, and the interest of competing great powers all overlap, the price tag on the Korean Peninsula is extremely high. Military might is not the only element that could ensure avoiding misunderstanding; it is the ability to clearly recognize historical patterns that transform crisis into war, and victory into protracted instability.

Although history does not repeat, it often rhymes. To fully understand the rhymes of 1870 would be a sine qua non for guaranteeing stability in one of the world’s most unstable regions.

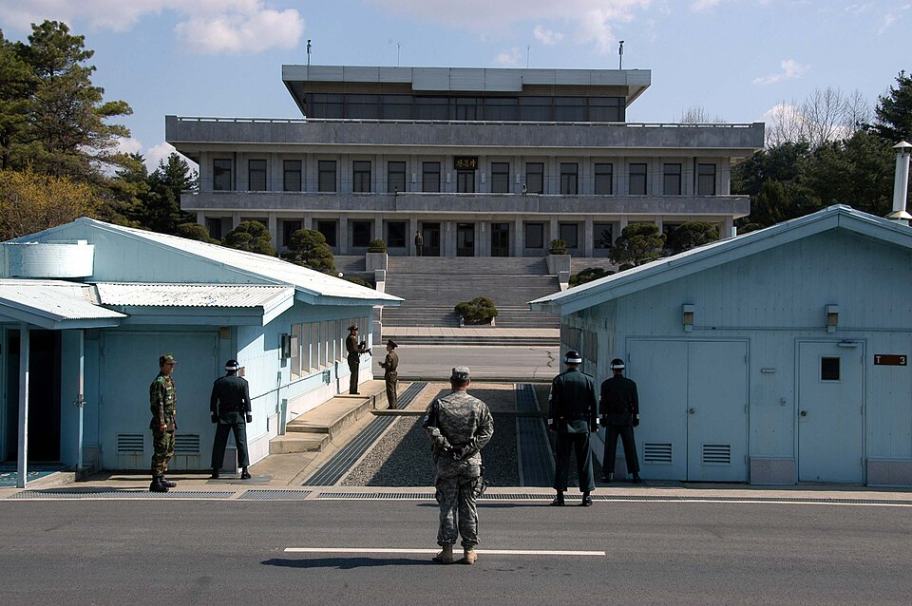

[Header image: View of the North from the southern side of the Joint Security Area (DMZ). Credit: Driedprawns at en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

Dr. Ju Hyung Kim currently serves as the president at the Security Management Institute, a defense think tank affiliated with the South Korean National Assembly. He has been involved in numerous defense projects and has provided consultation to several key organizations, including the Republic of Korea Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Defense Acquisition Program Administration, the Ministry of National Defense, the Korea Institute for Defense Analysis, the Agency for Defense Development, and the Korea Research Institute for Defense Technology Planning and Advancement. He holds a doctoral degree in international relations from the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) in Japan, a master’s degree in conflict management from the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), and a degree in public policy from Seoul National University’s Graduate School of Public Administration (GSPA).