South Korean Army soldiers and tanks participate in media day for the 77th Armed Forces Day at a military base in Gyeyong-City, South Korea, on September 29. File Photo by Jeon Heon-kyun/EPA

Nov. 21 (UPI) — The Republic of Korea-U.S. alliance is modernizing at speed, but its command architecture remains anchored in an earlier era.

Seoul and Washington have agreed to expedite the roadmap for wartime operational control transition, pursue full operational capability certification in 2026, and raise Republic of Korea defense spending toward 3.5% of gross domestic product.

They also have agreed to deepen extended deterrence and expand combined activities, from the maintenance of U.S. warships in Korean shipyards to advanced defense industrial cooperation.

Yet, beneath this progress lies a structural problem. Korea’s next war will not stay on the peninsula. It may not even start there.

North Korea‘s nuclear and missile forces already hold targets at risk across the region and in the United States. Chinese and Russian air, naval, cyber and political warfare capabilities intersect over the peninsula and its approaches. Dual contingencies involving Korea and Taiwan are no longer theoretical. They are operational planning assumptions.

The Indo-Pacific Command is responsible for this entire theater. It must deter and, if necessary, fight at least two major fights at once.

That scale creates a fatal gap for Northeast Asia. The alliance needs a dedicated, combatant command with Title 10 authority in Korea that can defend and, if required, defeat threats to the Republic of Korea from on and off the peninsula, while integrating nuclear and conventional operations and deterring third-party intervention by China and Russia.

Title 10 authority is what allows the military to conduct operations both domestically, when authorized, and abroad, under the direction of civilian leadership.

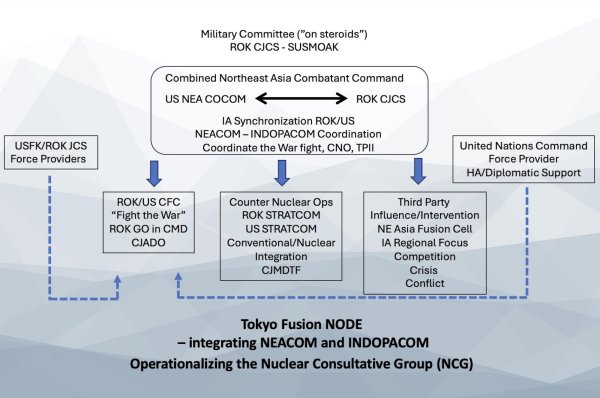

Northeast Asia now needs a dedicated “strategic brain.” That means a U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command in Seoul with Title 10 authority. It must be part of a binational combined command alongside the Republic of Korea’s chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, or in short, the permanent Military Committee on steroids.

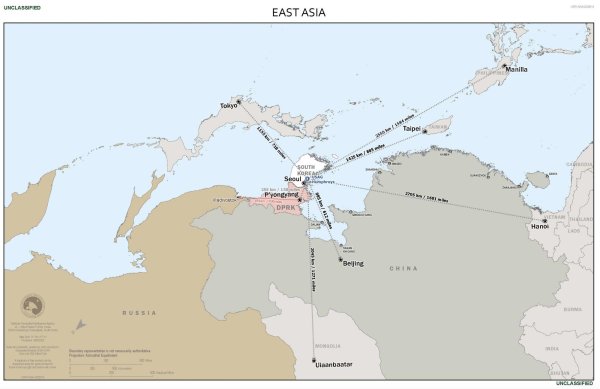

East-Up Map: Seeing the Theater From Korea

East-up map centered on Camp Humphreys and Seoul, showing distances from Korea to Pyongyang, Beijing, Vladivostok, Tokyo, Taipei, Manila, Hanoi, and Ulaanbaatar. Illustration by U.S. Forces South Korea/National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

The new “east up” map, highlighted by the U.S. Forces Korea commander, shows why this matters. Rotate the usual north-up orientation. Center the view on Korea instead of North America. The theater looks different.

Seoul/Camp Humphreys sits about 158 miles from Pyongyang, roughly 612 miles from Beijing, and within easy reach of Vladivostok. Seoul emerges not as the far end of a supply line, but as a central pivot already inside the first island chain.

The same map reveals a strategic triangle. Korea, Japan and the Philippines form three vertices that control key sea and air routes. Korea provides central positioning and the ability to impose immediate costs on North Korean, Chinese and Russian forces. Japan anchors advanced capabilities and critical maritime chokepoints. The Philippines offers southern access routes and control over sea lanes that connect the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

This is more than cartography. It is an operational picture that points to a simple conclusion. A theater that looks this interconnected requires a theater command grounded where those connections meet. That is the case for a U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command.

Why NEACOM Is the missing command brain

On any given day, the alliance faces at least three overlapping challenges.

Kim Jong Un‘s growing nuclear and missile arsenal targets Seoul, Tokyo, Guam and the American homeland. Chinese and Russian air, naval, cyber and information operations intersect over and around the peninsula. Continental-based U.S. forces expected to fight in Korea and those in Japan are already dual-tasked for contingencies involving Taiwan and other regional flashpoints.

We are asking one command in Hawaii to juggle all of this in real time. In a crisis, distance and the pace of events will make that impossible.

A U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command would fill the gap. A four-star U.S. combatant command headquarters in Seoul would take responsibility for theater-level planning and operations in and around Korea and Japan.

In practical terms, that commander is already the senior U.S. military officer assigned to Korea and the focal point for the northern leg of the strategic triangle. In parallel, a combined U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command. co-chaired with the Republic of Korea Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman, becomes the permanent four-star Republic of Korea-U.S. body that orchestrates alliance operations in Northeast Asia as well as potential support throughout the Asia-Indo-Pacific region.

The existing Combined Forces Command remains the warfighting headquarters charged with defending the Republic of Korea and defeating the North Korean People’s Army. U.S. Forces Korea continues to provide U.S. combat power and key enablers. The United Nations Command retains its legal and political roles, including access to bases in Japan.

What changes is the level above. U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command becomes the conductor. The Combined Forces Command fights and wins against North Korean forces. The U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command. manages the wider battlespace that the east-up map reveals, including Chinese and Russian behavior, missile trajectories that cross multiple countries, cyber campaigns, space assets and information operations across the strategic triangle.

Nuclear integration and trilateral defense

One of the strongest arguments for a U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command is nuclear integration. Seoul and Washington have built the Nuclear Consultative Group into the centerpiece of alliance nuclear policy and planning. The group has deepened transparency and strengthened the political credibility of extended deterrence. But it remains a planning body.

Without a theater combatant command that can turn consultation into executable operations, the alliance risks a gap between words and war plans.

Within the U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command, a dedicated counter-nuclear operations function could connect Republic of Korea Strategic Command, U.S. Strategic Command, and the Nuclear Consultative Group.

It would integrate missile defense, precision strike, cyber, space and information capabilities into a single framework designed to deny North Korea any illusion of escalation dominance.

It also would give commanders in Seoul the tools to use the geography of the strategic triangle to complicate Chinese and Russian decision-making in a crisis, working with Japan and coordinating with the Philippines to create multiple dilemmas rather than a single axis of pressure.

Japan is central. U.S. Forces Japan is both a contribution to the shield for the Japanese homeland and the springboard for reinforcing Korea through designated U.N. Command bases. In any real emergency, the same aircraft, ships and logistics routes will be pulled in different directions.

The U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command. concept therefore calls for a Tokyo fusion node. This is the standing mechanism where U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command and United States Indo-Pacific Command staffs sit together, plan together and manage dual-apportioned forces based in Japan. In peacetime they align plans. In crisis they coordinate rapid shifts in command relationships to match the fight.

NEACOM Organizational Structure

A modernized organizational structure for comprehensive combined planning and operations–the strategic brain. Chart by David Maxwell/UPI

Critics will say another command is simply more bureaucracy and that there just is not the force structure for a new command. However, the U.S. Northeast Asia Combatant Command and the Tokyo fusion node can be created from existing United States Forces Korea, Eighth Army and United States Forces Japan staffs. A comprehensive review and analysis will show that some headquarters could be eliminated by assigning the right missions to the appropriate commands.

Beyond armistice: preparing for peace and unification

There is also a wider horizon. The long-term strategic objective on the peninsula remains a free and unified Korea that is stable, non-nuclear and aligned with rules-based international order. That path is urgent and deserves sustained diplomatic, economic and informational support, even if it is not the main subject of a command plan.

The command wiring we build today for deterrence and defense will also be the wiring that manages denuclearization, stabilization and any transition that follows collapse or defeat of the Kim family regime.

A Seoul-based Northeast Asia Combatant Command, with a combined structure and established links to Japan and the broader region, would be the logical headquarters to manage the external military dimensions of that transition, while the Combined Forces Command supports the political efforts toward unification in the northern part of Korea.

Modernizing strategy, not just hardware

The Republic of Korea–U.S. alliance is already modernizing. South Korea is raising defense spending, fielding advanced capabilities and employing greater advanced capabilities. The United States is expanding industrial cooperation, deploying more capable assets and deepening nuclear consultation. Those steps are necessary.

They are not sufficient if the command brain remains stuck in a different era.

The east up map shows that Korea is not the distant end of a supply line. It is the central pivot of a strategic triangle that links Korea, Japan, and the Philippines and sits inside the first island chain.

Northeast Asia Combatant Command is the command architecture that matches that reality. Creating this command in Seoul, tied to Indo-Pacific Command through a fusion node in Tokyo and grounded in a truly combined partnership with the Republic of Korea, is how the alliance turns geographic advantage into real deterrence and ultimately victory and a free and unified Korea.

Korea’s next war, if it comes, will not stay in Korea. The Northeast Asia Combatant Command is how the alliance shows it understands that fact and intends to prevent that war from happening at all while establishing the military conditions to support a free and unified Korea.

David Maxwell is a retired U.S. Army Special Forces colonel who has spent more than 30 years in the Asia Pacific region. He specializes in Northeast Asian security affairs and irregular, unconventional and political warfare. He is vice president of the Center for Asia Pacific Strategy and a senior fellow at the Global Peace Foundation. After he retired, he became associate director of the Security Studies Program at Georgetown University. He is on the board of directors of the Committee for Human Rights in north Korea and the OSS Society and is the editor at large for the Small Wars Journal.