South Korea’s Defense Intelligence Agency warned in a Nov. 5 closed-door parliamentary audit that North Korea “could carry out a nuclear test within a short period of time.” The agency highlighted Tunnel No. 3 at the Punggye-ri nuclear test site as the likely location, stating it was “already physically possible to conduct nuclear tests in Tunnel No. 3” if leader Kim Jong Un gave the order.

Experts believe Tunnel No. 3 could be used to test the miniaturization of nuclear warheads, suggesting any new test would not just be a show of force but aimed at deploying operational technology.

Using high-resolution satellite images, I took a look at the recent status of the Punggye-ri nuclear test site in Kilju county, North Hamgyong province. Three of the site’s four tunnels remain closed, while Tunnel No. 3 has stayed open since its restoration around May 2022. I detected no vehicles or human activity in the images. Nor did I detect preparations for a nuclear test at Tunnel No. 3, such as the installation of instruments, power lines or cables. Although there were no signs of an imminent test at Punggye-ri, the authorities have maintained and managed the facility to enable the resumption of nuclear testing whenever the leadership decides to do so.

With North Korea expected to suffer more than gain from a seventh nuclear test, carrying out such a test would not be an easy decision. However, the country could restart nuclear tests depending on trends in its diplomatic relations and several dynamic factors in the international political environment, and I cannot rule out the possibility of North Korea’s spontaneous and impatient young leader carrying out a surprise test.

Recent movements at Punggye-ri nuclear test site

Tunnel No. 3, one of the Punggye-ri nuclear test site’s four closed tunnels, was reopened in 2022 and remains usable at any time. No signs of an impending nuclear test were detected in the satellite images. (WorldView-2)

Tunnel No. 3, one of the Punggye-ri nuclear test site’s four closed tunnels, was reopened in 2022 and remains usable at any time. No signs of an impending nuclear test were detected in the satellite images. (WorldView-2)

At North Korea’s only nuclear test site, located at Punggye-ri, Kilju county in North Hamgyong province, there are four tunnels for nuclear tests. All of them are closed, except for Tunnel No. 3 in the south. Tunnel No. 1 in the east was closed after North Korea’s first nuclear test in October 2006, while the other three were sealed when their entrances were blown up during North Korea’s theatrical closing of the Punggye-ri test site in May 2018. Tunnel No. 3 was restored for use in nuclear tests around May 2022, when the North opened a roundabout entrance. The entrances to tunnels No. 2 and No. 4 have remained sealed since the 2018 explosions and rockslides blocked them.

In high-resolution satellite images taken on Nov. 3, I detected no preparations or signs of an imminent nuclear test at the restored Tunnel No. 3, including installed instruments, cables or power lines. In particular, I saw no signs of movement at the site’s administrative support facility, including people or vehicles. Meanwhile, I discovered a 0.1-hectare cultivated plot on the hillside above the support facility, and a 0.5-hectare plot above Tunnel No. 2. I believe the plots at the Punggye-ri nuclear test site are farmed by soldiers guarding the site. On the other hand, some people claim the plots are cultivated by convicts mobilized from a nearby political prison camp. About 25 kilometers east of the nuclear test site, on the other side of Mt. Mantap, is the notorious Myonggan (or Hwasong) political prison camp, also known as Camp No. 16. Camp prisoners were mobilized to dig the nuclear test tunnels and other facilities at the site, but this has never been confirmed. Infamously, nobody has ever escaped from Camp No. 16 and lived to tell the tale. Because the camp is isolated deep in the high mountains, escape is practically impossible.

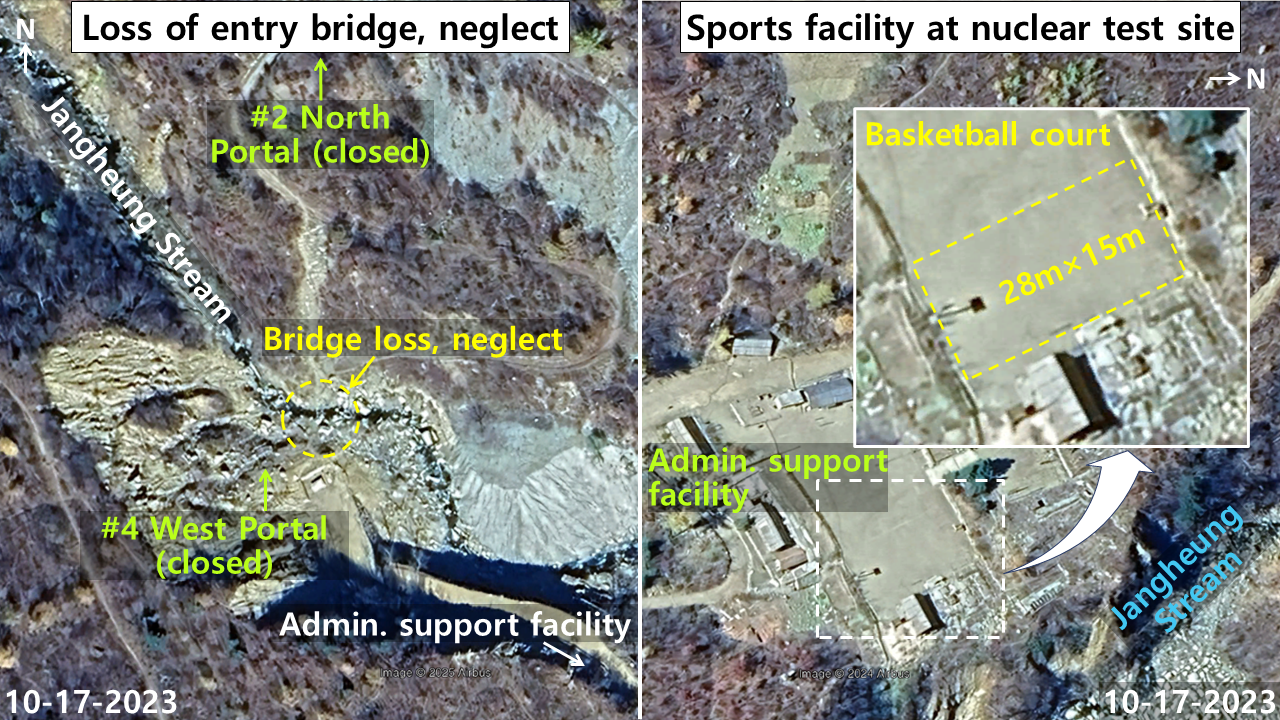

The bridge on the road connecting tunnels No. 2 and No. 4 was washed away years ago by heavy rains and flash floods and remains unrestored. The administrative support facility’s lot has a basketball court. (Google Earth)

The bridge on the road connecting tunnels No. 2 and No. 4 was washed away years ago by heavy rains and flash floods and remains unrestored. The administrative support facility’s lot has a basketball court. (Google Earth)

A stream flows between Punggye-ri’s tunnels No. 4 and No. 2, and there used to be a bridge connecting the two tunnels. The bridge was washed away by summertime torrential rainfall and flash floods years ago, and satellite images show that it has yet to be restored. If one follows the road from Tunnel No. 4 downward for about 250 meters, it connects to the administrative support facility.

In the satellite image, the administrative support facility has a sports facility. In the lower part of the empty lot, one can faintly make out the white sidelines of the basketball court, with two nets 28 meters apart. One can also make out the shadows of the baskets. I estimate the court to be 28 meters along the sidelines and 15 meters along the baselines, which matches International Basketball Federation (FIBA) regulations. That camp prisoners mobilized to build the nuclear test site would use the basketball court is unthinkable; I believe soldiers guarding or managing the facility use it during their free time. I have yet to detect anyone actually using it in satellite images.

Possibility of a seventh nuclear test

My interim conclusion is that if North Korea restarts nuclear tests at the Punggye-ri nuclear test site, it will do so at Tunnel No. 3. North Korea restored Tunnel No. 3, which had been sealed with much explosive fanfare in 2018, and has kept it in usable condition since 2022. Some experts believe that North Korea could restart nuclear tests depending on trends in its diplomatic relations and several dynamic factors in the international political environment. For a seventh nuclear test, North Korea could conduct a highly explosive megaton-level test of a magnitude much higher than in the past to demonstrate the development of its nuclear arsenal, but it could also conduct less powerful tests in line with its strategy to miniaturize its nuclear weapons and develop multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) technology.

To sum up, I believe North Korea can conduct a seventh nuclear test at Punggye-ri and that it has made substantial technical and policy preparations to do so. However, when and at what scale it will do so remains unclear, and I believe various diplomatic and security variables will largely determine the answers. A seventh nuclear test could yield North Korea strategic benefits in the short term, but it could also incur substantial risks and costs in the medium and long term. I think an additional nuclear test is a double-edged sword, and the key is when and how North Korea brandishes that sword and how much it can endure the response that follows.